I generally provide a bit of detailed information with the quiz answers. Old Father Time, however, wouldn’t allow me to do so. Please enjoy the following findings about our Appalachian language from Appalachian English Quiz 5. Click the gallery images to look closer.

Aim to

The Free Dictionary by Farlex defines “aim to (do something)” as: “to intend, plan, or mean to do something.” The word “aim” is part Anglo-Norman/ part French and is believed to have first been used in the 1130s.

“Aim” was allegedly first in print in 1595 in The Trumpet o[f] Fame: or Sir Fraunces Drakes and Sir Iohn Hawkins F[are]well by Henry Roberts. In 1598, the word was in John Florio’s Dictionary World of Wordes at Mira and is defined as “An aime, a levelling, an intent or purpose.”

“Aim” used in the form of “to intend, to plan,” is mainly used in the South.

Favor

The word “favor” comes from Middle English via the Old French favour (modern French faveur). The usage “Family resemblance; Appearance; a liking”1)The Dictionary of American Regional English occurs mostly in the South and is believed to be outdated, or simply dialect in the southern areas. Mark Twain used the word in this context in The Prince and The Pauper.

The word first appeared possibly in the 14th century. The earliest printing may have occurred in the 1500s in The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian (aka Aesop’s Fables: Trial of the Fox) by Robert Henryson.

During research, I found the usage in a great amount of slave dialogue, which suggests the usage first originated from African Americans.

Ov’air (also Ov’Ar)

According to the Free Dictionary by Farlex, “Over there” means “at some location that is an unspecified distance away.”

In World War I, the phrase characterized military deployment overseas, referring to soldiers stationed in Europe, particularly the Western Front. Listen to the song here:

The words “over there” and “overthwart” (meaning “across, transversely”) may have some connection.

Let’s break down the phrase a bit. The word “over” came about via the Germanic language, from the Old English ufer/ ofaer/ obaer, etc. In Middle English, the word was offerr/ oouer/ ouur/ owver, etc. In the 1800s, the word was recorded as auver/ awver/ hover, etc.

The word first appeared in print in Paulus Orosius’s Histories against the Pagans, written in the early 400s:

He eode to ðære burge wealle & fleah ut ofer. (emphasis added)

The word “there” originates from the Old English “þǽr, þár, þér” and stems from the Proto-Germanic word thær. The Old Saxon is thâr, the Middle Low German is dār, and the Middle Dutch is daer.

The word “there” has various pronunciations: thurr, dah, thar, dare, air, ere, thore, etc. The pronunciation “thar,” comes from Middle English. The “air”/ “ere” pronunciation first appeared in print in 1825 in John Neal’s Brother Jonathan.

Posta

Information is little to none about this pronunciation. I have also heard: “aposed to,” “sposta,” and “poster.” I encountered the latter from an elderly woman down our holler.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “supposed” is borrowed from the French supposer. The Middle English is sopos/ supposse/ subpose, etc. In pre-1700s Scotland, the word was supois.

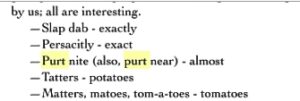

Purt/ Pert near

The words “pretty near it” mean “nearly” or “almost.” In an eastern Kentucky dialogue collection from 1911, the speaker says “prettynēart,” meaning “almost”:

“He was prettyneart sick.”

Another way of saying it is “purt night,” seen in another collection from 1935:

“The reddishes are purt night big enough to have a mess.”

Journalist and publisher Gary Matthews laments the lack of sources for this phrase in his blog. He provides a very spot-on definition:

‘pert near’ is a slang expression meaning ‘pretty nearly’ or ‘darn close to’.

He also provides a very witty tidbit–There is (or was) a website named Pertnear.com.

Sorry

The word “sorry” was inherited from the Germanic language. One form of the word in Old English was sarg, which changed into sarig/ soori/ soory, etc. by early Middle English, where it then morphed into sary in Middle English. By late Middle English, the word was sorry.

The use defined as a “wretched, pathetic; poor [person]” first appeared in print in 1225 in Richard Morris’s Old English Homilies and Homiletic Treatises. The usage as “a poor or inferior example of something; of little account or value; pathetic,” was first in print in about 1372, noted in Carleton Fairchild Brown’s Religious Lyrics of the XIVth century.2)Oxford English Dictionary

The word “sorry” in the sense of a “. . . failure to meet reasonable expectations; useless, shoddy, wretched”3)Dictionary of American Regional English is especially used in the U.S. Southeast, the Lower Mississippi Valley, Texas, and Oklahoma. The word used as “sickly, ill; lacking energy,” is mostly used in the South and South Midland.

The first time one of these usages was printed was likely in the June 1804 issue of Literary Magazine, and American Register.

In the online magazine, Cattle Today, the writer says:

I’ve seen grand champions at some of the most prestigious shows mature into animals so sorry they were never allowed to breed a cow.

I found the following from the book Smoky Mountain: A Lexicon of Southern Appalachian Speech Based on the Research of Horace Kephart informative and entertaining:

“Them sorry fellers” denotes scabby knaves, good-for-nothings. Sorry has no etymological connection with sorrow, but literally means sore-y, covered with sores, and the highlander sticks to its original import . . . “Some sorry fellers come in thar full o’ moonshine an’ shot their revolvers.”

Sparking

The word “spark” comes from the Old English spearca, meaning “glowing or fiery particle thrown off” from heat. The form changed to sparke in Middle English. In the 1570s, the word referred to a beautiful, elegant woman. In around 1600, the usage changed to “a gallant, a showy beau, a roisterer,” stemming from the Old Norse sparkr, which means “lively.”4)Online Etymological Dictionary

The meaning “courting, paying attentions”5)Oxford English Dictionary was formed within our own English language, likely as slang. This meaning is considered passé. The word in this dating/ love context first appears in 1790 in Royall Tyler’s The Contrast: A Comedy in Five Acts. (Act 2, Scene 2) The word was also recorded in Thomas Green Fessendon’s 1806 Original Poems.

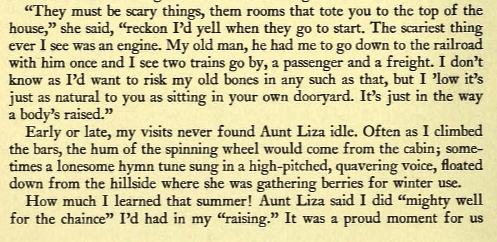

Chainch

The word “chance” comes from the Old French cheance, which is also the variation in Middle English. In Middle Scottish English, the word was chanss. From there, the word changed into the Middle English chaunce, and, ultimately, chance.

In Appalachia, the word is pronounced “chaince, chanch, chanc(e)t, chanst, charnce, and chaunce.”6)Dictionary of American Regional English I’ve only heard it pronounced as “chaince” and “chainch.” My father said “chainch” a lot.

In an episode of the television series Hell on Wheels, the main character, Cullen Bohannan, says the word “chainch.” The actor Anson Mount was so convincing, I had to look up his origins. He spent most of his childhood in Dickson, Tennessee. He attended Sewanee: The University of the South, also in Tennessee. So that’s where he learned the pronunciation.

The variant “chaince” can be found in Frances Louisa Goodrich’s 1931 book Mountain Homespun. In a 1970 personal recording in Tennessee, the word was pronounced “chanch.”7)Dictionary of American Regional English

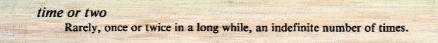

Time or two

According to Paul Green’s Wordbook, the phrase “time or two” means:

The Free Dictionary by Farlex lists the definition as “a (unit of time) or two,” in other words: a minute or two, an hour or two, a day or two, etc.

Hump up to

The Dictionary of American Regional English defines the word “hump” as “to make oneself smaller; to draw oneself in.” The Free Dictionary by Farlex says “hump” means “. . . to form or become a hump; hunch; arch.”

When I was little, wintertime was cold back in the dark holler. Sometimes, our family of four slept together in the living room, near the fireplace. My mom and dad would block off doorways by tacking up blankets, and we all laid on a pallet atop the floor. My dad sparked the fire in the fireplace, but, before the room warmed, my mom would ask if my brother and I were cold. If we were (which we were), she’d say, “Then hump up to me.” That meant spooning with her to keep us warm. I also remember my parents saying “humper up to.” I’m not sure where this phrase, in this context, originated.

Heered (also hyeerd)

The word “hear” and the past participle “heard” comes from the Germanic language. In Old English, the word was híeran/ hýran/ héran (in past tense híerde/ hýrde/ hérde). In Middle English, the word changed several times: heren, here, heare, heoren, hyere(n), her, hyre, herde, hered, hyerd, etc.8)Oxford English Dictionary

In the South and South Midland, “hear” is pronounced hyeah, hy(e)ar, hyere, heer(ed), heared. Some speakers pronounce the word as yeard, year, yerre.

In 1815, David Humphreys 9)David Humphreys was George Washington’s secretary who ranked colonel during the American Revolution, ran military intelligence for Ben Franklin, and served in Connecticut’s state legislature. wrote a play called The Yankey in England, where the word “heerd” is recorded. The variation is also in several of Davy Crockett’s Almanacs.

The aforementioned Smoky Mountain Voices: A Lexicon lists the pronunciation as :

Heerd, heered, hyerd = “[v. variants of heard, have heard] . . . ‘heerd, hyerd [are both] used by . . . school pupils regularly outside the classroom’ (Joe Morgan of near Ashville) 6 July 1926.”

Kyarn

The word “Kyarn” is actually a variant of the word “carrion”; and “carrion” began in about the 13th century from the Old Northern French word ca ‘ronië, later changing to caroine, caroigne, and charoigne. Middle English variations were many: caroine, karoyne, careyn(e), carraine, karyn, cariune, caryon, until the 1500s settled on carrion. In the South, the word is pronounced caian, caran, carrin, cyarn, kyarn. Many sources indicate the pronunciation kyarn originates from African Americans in Alabama and Georgia in the early 1900s.

If some odor was foul, my father would say it “smelled like kyarn.” He told me it was the same as smelling something rotten or feces (only he didn’t use the word feces).

Sangle

The word “single” comes from the Old French single, sengle, and also saingle, sangle, etc. Some odd variants appear in Middle English: cengylle, singill, syngil, etc. The word is defined as “sole, unaccompanied, individual, separate.” It was first recorded in the early 1300s.

I found no information about the pronunciation of the word, other than the aforementioned Old English style.

Swan/ Swanee

A God-fearing Appalachian person never swears; never says the words “I swear.” The reason stems from Jesus’s words in Matthew 5:34-37:

34 But I say unto you, Swear not at all; neither by heaven; for it is God’s throne:

35 Nor by the earth; for it is his footstool: neither by Jerusalem; for it is the city of the great King.

36 Neither shalt thou swear by thy head, because thou canst not make one hair white or black.

37 But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil.10)The Matt 5:34-37 reference is from the King James Version.

But . . . a person crafts a way around the issue by creating a phrase that’s not technically saying the word, not technically swearing.

The word “swan” used as a verb means “To swear; to declare . . . to express surprise, indignation, or emphasis . . .” The phrase “I/ I’ll swan” may originate from the Scottish “I’se warn” which means “I’ll warrant,” or “I’ll be bound.” The word “swanny”/ “swanee” means the same thing as “swan,” when it comes to swearing. The usages are considered old-fashioned.11)Dictionary of American Regional English A May 20, 1823, article in the Missouri Intelligencer admitted the word was a more genteel way to swear.

Breaking down the word “swear,” we see it comes from the Old English swerian, meaning, to “take an oath,” via the Germanic swērjanan.

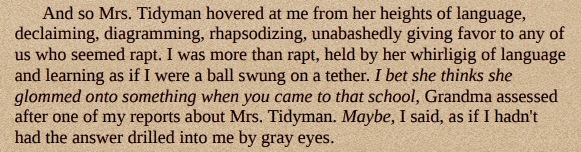

Glom onto

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “glom” means “to steal; to grab, snatch . . . usually const. on to.” (emphasis added)

For our Appalachian purposes here, the word “glom” means “to grab, get hold of, latch on to.”12)Dictionary of American Regional English Americans took the word glaum from the Scots and changed it to their own word glom. The first known use of “glom” seems to be 1907. The phrase also appeared in 1916 in a dialogue:

“He glommed onto my book.”

Spell

The word “spell,” defined as “a period of space of time of indefinite length,” first appeared in 1728 in J. Morgan’s A Complete History of Algiers.

The word also means “A period of being indisposed, out of sorts, or irritable; an attack or fit of illness or nervous excitement.”13)Oxford English Dictionary

Resstrint (also Resturnt)

The word “restaurant” originates from the French word restaurant. Other English variations are from the 1800s: restaurans, restaurant, restorong (←“attempt to imitate a French pronunciation”), restaurat, etc.

My paternal grandfather used to pronounce the word “resstrint” while my maternal grandmother and father said “resturnt.”

Piss-poor

The phrase “piss-poor” means “of an extremely poor quality or standard.”14)Oxford English Dictionary The phrase was first recorded in 1945 in Mackinlay Kantor’s book Glory for Me.

Al

The word “owl” is inherited from the Proto-Germanic uwwalon-. In Old English, the word began as ulae, then changed into Middle English ule, owlle, etc. In Early Middle English, the word was sometimes hule, hole, and howle. In the 1600s, the word became oole, and changed further until we have the current owl.

I’m not sure where the pronunciation “al” comes from. I heard it all my life around family circles, in addition to other words that are pronounced with the same short a sound:

- Howl = hal

- Dowel = dal

- Foul = fal

- Jowell = jal

- Powell (place in TN) = pal

- Towel = tal

Do What?

The phrase “Do what” is an interrogatory one for “What did you say?” or “Repeat that, please.” It may have begun in the late 1950s. Another phrase which means the same thing was “Do how?” and it was recorded earlier in the 1920s.15)Dictionary of American Regional English

Sources:

- “Everpoint” (J.M. Field, Esq., of the St. Louis Reveille) and Felix Octavius Carr Darley. 1847. The Drama in Pokerville : The Bench and Bar of Jurytown, and Other Stories. Philadelphia: Carey and Hart.

- Aesop, Robert Henryson. 1970. The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian. Amsterdam: Theatrum orbis terrarum.

- Alfred, King of England and Walter John Sedgefield. 524, 1899. King Alfred’s Old English Version of Boethius De Vonsolatione Philosophiae. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bailey, Nathan. 1730. Dictionarium Britannicum: or a More Compleat Universal Etymological English Dictionary. London.

- Brown, Carleton Fairchild. 1924. Religious Lyrics of the XIVth Century. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Cattle Today. n.d. Cattle Today. Accessed June 2023.

- Crockett, Davy. 1841. The Crockett Almanac: Containing Sprees and Scrapes in the West; Life and Manners in the Backwoods, and Exploits and Adventures on the Prairies. Boston: J. Fisher.

- Dictionary of American Regional English. n.d. Accessed June 2023.

- Doig, Ivan. 1978. This House of Sky. Orlando: Harcourt, Inc.

- Farlex. n.d. The Free Dictionary. Accessed June 2023.

- Finn, Henry James. 1831. American Comic Annual. Boston: Richardson, Lord and Holbrook.

- Florio, John. 1598. A Worlde of Wordes. London: Arnold Hatfield for Edw. Blount.

- Fowler, Roger R., ed. 1990. The Southern Version of Cursor Mundi. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa. 1931. Mountain Homespun. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Green, Paul. 2017. Paul Green’s Wordbook: An Alphabet of Reminiscence. Appalachian State University.

- Intelligencer. 1823. May 20.

- Johnson, Samuel. 1785. A Dictionary of the English Language. London.

- Kamerad Kosmos ,”Over There” – American Patriotic Song

- Kane, Elisha Kent. 1866. Arctic Explorations. London: Nelson and Sons.

- Kantor, Mackinlay. 1945. Glory for Me. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc.

- Lincoln, Joseph C. 1916. Mary – ‘Gusta. New York: A.L. Burt Co.

- Matthews, Gary. 2016. “One word: Pert Near.” Gary Matthews: Writing, Publishing, and Design. Feb 19.

- Mayhew, Walter W. Skeat and Anthony Lawson. 1914. A Glossary of Tudor and Stuart Words. Oxford.

- Merriam Webster’s Dictionary. n.d. Accessed June 2023.

- Morgan, J. 1728-29. A Complete History of Algiers to Which is Prefixed an Epitome of the General History of Barbary, from the Earliest Times. London: J. Bettenham.

- Morris, Richard. 1868. Old English Homilies and Homiletic Treatises. London: N. Trubner & Co.

- Neal, John. 1825. Brother Jonathan: Or, The New Englanders. Edinburgh: William Blackwood.

- Online Etymological Dictionary. n.d. Accessed June 2023.

- Oxford English Dictionary. n.d. Accessed June 2023.

- Rawlings, Marjorie Kinnan. 1945. South Moon Under. New York: Bantam Books.

- Reynolds, Henry. 1595. The Trumpet o[f] fame: or Sir Fraunces Drakes and Sir John Hawkins f[are]well. London: Thomas Creede.

- Roberts, H. 1595. The trvmpet of fame, o[r], Sir Frances Drakes and Sir John Hawkins f[are]well. London: Thomas Creede.

- Scribner’s Magazine. 1887.

- Slone, Verna Mae. 2009. How We Talked and Common Folks. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- Smith, Seba. 1970. The Select Letters of Major Jack Downing. Upper Saddle River: Literature House/ Gregg Press.

- Smoky Mountain Voices: A Lexicon of Southern Appalachian Speech Based on the Research of Horace Kephart. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- The Literary Magazine, and American Register. 1804. The Literary Magazine, and American Register, June.

- Thomas Green Fessenden, Esq. 1806. Original Poems. Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press of E. Bronson.

- Twain, Mark. 1921. The Prince and the Pauper. New York: P.F. Collier & Son Co.

- Wilbur, Royal Tyler and James Benjamin. 1920. The Contrast: A Comedy in Five Acts. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Internet Archive

**Featured image from Pexels via Pixabay

References

| ↑1 | The Dictionary of American Regional English |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑5, ↑8, ↑13, ↑14 | Oxford English Dictionary |

| ↑3, ↑6, ↑7, ↑11, ↑12, ↑15 | Dictionary of American Regional English |

| ↑4 | Online Etymological Dictionary |

| ↑9 | David Humphreys was George Washington’s secretary who ranked colonel during the American Revolution, ran military intelligence for Ben Franklin, and served in Connecticut’s state legislature. |

| ↑10 | The Matt 5:34-37 reference is from the King James Version. |

“Do what?” is akin to “Shot who?” Both are all-purpose remarks by incredulous Southerners. Also, “piss poor” may be related to how very poor folks would pee in a pot and sell the pee to tanneries. That was definitely the origin of “without a pot to piss in,” which meant reeeeally poor.