It was the farthest north they had ever been. It being Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. They being George Washington Cline and Henry Lafayette Marcum of Mingo County, Virginia, which bordered Kentucky in the southwestern part of the state. Most people there in Mingo County were related to each other. George and Henry were cousins, and they had never been more than fifty miles from their mountain homes until the war came along.

It was July 2, 1863, and they were soldiers now in the Rebel Army. A rumor had been floating about for the last week or so that on June 20th the western counties of Virginia had seceded and formed their own state called West Virginia.

“So, you think it’s true George that Mingo County and the other western counties have formed their own states?”

“Yes, I do Henry, and you know why?”

“Why?”

“Because we mountain folk got drug into this war against our will, that’s why. We were always against secession, against slavery, too. Nobody wanted their husbands, sons, brothers, or other family members going off and fighting and dying so them rich plantation owners could sit at home on their butts, sip mint juleps, and keep their slaves. I tell ya Henry, us mountain folk eking a living out of the side of a mountain have got nothing at all in common with them plantation people. Thank God and amen that we cut loose from them.”

“So, we’re no longer Virginians then. We’re West Virginians now?”

“Yes, that’s right. We’re West Virginians now.”

“But we joined up and took an oath to fight for the Confederacy, George.”

“We were just dumb teenage kids back then, Henry. We got caught up in all the excitement of going off to war and glory and all that nonsense. We went along with our state just like Lee went along with Virginia when he chose to fight for Virginia instead of fighting for the Union. So, the way I figure it now is that if Lee can fight for his state, then we can fight for ours, and our state now is West Virginia, not Virginia.”

“What are we going to do then?”

“Well, I for one am not dying for the Confederacy now that things have changed. That’s for damn sure. When we go into battle tomorrow, as soon as I see the first man go down, I’m going to fall down, too, and pretend I got shot.”

“Then what?”

“Then I lay there until the battle is over, get up, and say I got knocked out when one of our own men crashed into me and hit me in the head with his rifle butt. That’s what.”

“But you won’t have the bump to prove it.”

“Oh yes I will.”

“But then what after all that?”

“Then I’m deserting the first chance I get and join the Union army.”

“But if you get caught, you’ll be shot for treason.”

“Well, the way I figure it is that I have a better chance of getting shot tomorrow when we assault the Yankees than getting caught and shot for treason. I strongly advise you to do the same thing if you know what’s good for you.”

“I’ll sleep on it, George.”

But Henry didn’t sleep much on it that night. He was up and down all night long, a nervous wreck, for how could he sleep knowing that tomorrow that they’d go into battle by running across an open field fully exposed to Yankee fire high up on a ridge, ironically called Cemetery Ridge, about 800 yards away? He was on the proverbial horns of a dilemma torn between doing his duty as a soldier, which he had signed up for and had sworn to do, or breaching his oath and going over to the other side like George was planning on doing.

Tomorrow came, as it always does, and Henry and George crouched down, their death grip on their rifles, waiting for the bugler to blow “Charge,” the call that would summon them to the Field, not the Valley of Death. The signal came late that afternoon around 4 p.m., and, as soon as the bugler blew, they had no choice but to go forward since the men in front of them had advanced, and the men behind them were pushing them forward. So, they got swept up in the tidal wave of Rebel humanity, but neither of them let out the Rebel yell like everyone else was doing.

They ran forward together, side by side, troops in front of them, troops behind them, troops alongside them, and, when they got to about four hundred yards or so from the ridge, that’s when they saw the first man go down. On cue, George took a dive. Henry ran over to him, dropped his rifle, bent down, grabbed George by his shirt, and tried to pull him to his feet. But George resisted.

“Get up. Get up! I’m not going to let you do this George. I’m not going to let you disgrace yourself like this.”

Henry yanked George again. George fought back again, resisting with every ounce of strength in his body, remaining glued in place.

“Let go of me Henry. Let go of me!”

“George, I can’t let you do this. I can’t let you do this. It’s wrong.”

“Let go of me Henry. Let go of me. I’m warning you.”

“Warning me what George? That you’re going to shoot me if I don’t let go of you? Get up and do your duty as a soldier that you swore to do, Soldier.”

“My duty is to myself and your duty is to yourself. So go fall down somewhere.”

“Okay fine then. I’ll just tell folks back home what you did. That you were a coward.”

“Don’t you dare,” warned George as he pointed his rifle at Henry’s chest.

“You won’t shoot me, George. You won’t shoot your own cousin now, will you?”

“Oh yes, I will. Yes, I will. Don’t make me do it.”

“Well then, if you’re going to shoot me, I might as well make it so that you shoot me in the back like the coward you really are so that everyone knows it.”

Henry released his hold on George, picked up his rifle, stood up, and turned his back on George.

No, George didn’t shoot Henry in the back. A Yankee shot him in the chest and he fell backwards on top of George. George made no attempt to push Henry off of him. He took Henry’s death as a mixed blessing in disguise, figuring that if anyone came along and saw Henry lying on top of him, they’d figure he was dead, too. So, George let Henry bleed out on him, soaking his shirt, his pants, his underwear, counting on Henry’s blood passing for his own, and being further proof of his own death. At least this way he wouldn’t have to knock himself in the head now, would he? And he could sneak away at night when the battle was over. This was even better than he had originally planned.

Then, all of a sudden, someone yanked Henry off him. It was his sergeant.

“You okay George?”

“I’ve been shot.”

“Oh, I see that now, all that blood. Can you walk?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Well, you better try. We’re falling back and if you don’t get back now, there’s no telling when we’d get someone out here to get you. You might die before then if you don’t get that wound looked at immediately. It looks pretty bad from all that blood.”

His sergeant turned around and grabbed the first two men running by him.

“Here. You two men help this man here on his feet,” he told them, “and take him back with you. He’s been shot.”

The two privates looked at George lying there all bloodied up, then at their sergeant in disbelief of such a ridiculous request to take an obviously dying man back with them, a man who would only slow them down. The look on their faces sent the message loud and clear that they didn’t want to do this. That they wanted to get the hell out of there and back to the safety of their own lines as soon as possible. They stood there dumbfounded, defiantly refusing to move.

Their sergeant was not about to be disobeyed.

“That’s an order privates! Do it and do it now or face court martial proceedings when we get back.”

The two privates reluctantly came forward, helped George to his feet, and, with one on each side of him, they started back with George in tow. Their sergeant, satisfied now that his order was being obeyed, turned around and kept shouting and waving for the men to fall back and retreat. After the two privates carried George some distance, and when they were sure they were out of their sergeant’s sight, they suddenly let go of him. They didn’t even turn around to see if he collapsed to the ground or not. They just took off running.

George never faked a fall. He stood there and waited until the two privates were out of his sight. Then he, too, joined the wave of gray humanity washing back to the safety of their own lines.

Gettysburg was the farthest north that George had ever been in his entire life. Ditto for Henry.

B. Craig Grafton is a retired attorney and author of the following books published by Two Gun Publishing: Willard Wigleaf: West Texas Attorney; Jill Driver: Trail Boss; Daniel Shepherd: Soldier, Lawman, Lawyer, and Western and Southern Fried Dramas. The Scarlet Leaf Review has published his book Twenty First Century American Fairy Tales.

Click the following images to find Grafton’s work:

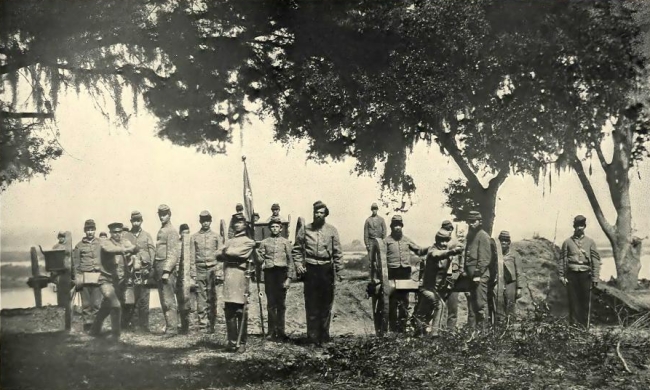

**Featured image: Image by smallbod, Pixabay, altered b&w