Appalachia Bare recently published Stephen Billias’s poem, “Little Margaret,” a thoughtful and earnest homage to his friend, James Elton “Jim” McMillan, Jr., who was, among many talents, a musician. Stephen’s poem “Little Margaret” is the namesake of one of Jim’s songs. Stephen generously passed along a recording of Jim and his band singing “Little Margaret” and we were very honored to include it. Persons familiar with ballads, particularly ballads sung in Appalachia, may recognize the song’s lyrics are borrowed from a ballad called “Fair Margaret and Sweet William.” Indeed, Stephen includes some of these lyrics in his poem:

“Little Margaret’s layin’ in a long black coffin with her face turned toward the wall.”

“Three times he kissed her cold, cold hand, twice he kissed her cheek,

And once he kissed her cold, cold lips, and then he in her arms asleep.”

The reader may remember an article I posted a few years ago, titled “The Ballad of Barbara Allen.” The article introduces my great-grandmother, how she learned this ballad from her mother in the late 1800s, and sang the song to my mother. So many ballads were brought to Appalachia from our motherlands.

Stephen’s poem (and Jim’s song) “Little Margaret” offers us a doorway to a ballad that appeared in popular culture as recently as 2003 in the soundtrack from the movie Cold Mountain (#13 “Lady Margaret”). So, come along with me and we’ll walk a little exploration trail into this ballad. For reference, the entire ballad (at least one version) is found at the end of this article.

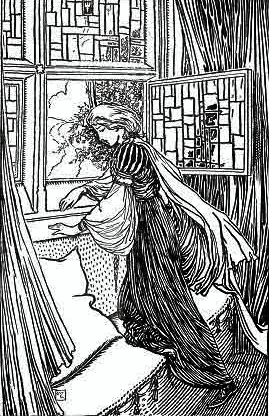

Allow me to briefly summarize. Fair Margaret and Sweet William sit on a hill and a break up occurs. William tells her he’s marrying someone else.1)In some versions his bride is described as “brown” or “nut-brown.” Way back when, these were derogatory terms for a “plain woman, that could also describe a sallow-skinned or sunburnt woman.” With a little guesswork, and with a smidgen of knowledge of the times, one might say he left Fair Margaret and married for money and acreage. Later, she watches Sweet William’s marriage procession from her high bedroom window.2)Some versions say “high hall door,” or “high hall chair” instead of window. Margaret dies either by suicide or of a broken heart, depending on the version. Her ghost materializes before Sweet William to ask him if he loves the bed, the pillow, the sheets, and the new bride more than herself. William replies he loves the bed, the pillow, the sheets, but loves Margaret “best of all.” As the night wears on, nightmares plague him into the morning. After waking, William rides to Margaret’s estate to search for her. He knocks on the door and asks after her. Margaret’s family tells him she is dead and lead him to her coffin. Sweet William kisses her face, cheek, chin, and lips, after which, he, too, dies of a broken heart in her cold arms. Other versions say he died atop her grave or the next day. They are buried beside each other. A rose grows from her grave and a briar grows from his. The rose and briar grow “until they formed a true lover’s knot.”

One can never really tell when a ballad began. But a few lyrics from “Fair Margaret and Sweet William”3)The ballad is also known by “Lady Margaret and Sweet William.” appeared in the 1611 Beaumont and Fletcher play, The Knight of the Burning Pestle:

In came Margarets grimely ghost

And stood at Williams feete.4)Beaumont, Francis, and John Fletcher. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. ed by Murch, Herbert S New York, H. Holt, 1908. Library of Congress. ii, 8.and

You are no loue for me Margret, I am no loue for you.5)Beaumont, Francis, and John Fletcher. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. ed by Murch, Herbert S New York, H. Holt, 1908. Library of Congress. iii, 5.6)Most versions have “harm” instead of “loue”/ love.

The ballad in its entirety first appeared in print as “Fair Margaret’s Misfortune” in a 1720 broadside; and Francis J. Child published the ballad as #74 in his extensive volumes, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. As I mentioned in the “Barbara Allen” article, Child, a scholar and folklorist, is arguably the nation’s most well-known ballad collector.

Like all ballads, several versions exist of “Fair Margaret and Sweet William.” Now, I am not a music scholar, nor do I pretend to be. I’ll say that right off. But I will do my best to piece together versions and years and as much of anything else I can for this article. Please forgive any confusions or prattling.

Controversy about this ballad fomented in the early 1700s. In 1711, another ballad emerged titled “William and Margaret: An Old Ballad.” The story unfolds the same but is written “in a more ‘literary style.’” Most writers at the time attributed “William and Margaret” to Scottish poet and playwright David Malloch (aka Mallet). In 1724, he published another version, this time in his name, called “Margaret’s Ghost.”

At the time, some scholars believed Malloch’s ballad and “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” were closely related. Francis J. Child said Malloch’s version was “simply ‘Fair Margaret and Sweet William’ rewritten in what used to be called an elegant style.”7)English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child; Helen Child Sargent; George Lyman Kittredge. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Co. 1904. p. 157. The style between the two is definitely different, and the “elegant style” lends a different tone. Aside from the first stanza, proving a rewrite is difficult, and, even though similarities exist in that stanza, the fourth line is different. In “Fair Margaret and Sweet William,” the line reads: “Little Margaret appeared all dressed in white,/ A-standing at their bed-feet,” while “William and Margaret” reads: “In glided Margarets grimly ghost/ and stood at William’s feet.” Supernatural elements in Malloch’s version are more forced and a little gothic. The narrative structure between the two are different. The English Folk Dance and Song Society explains:

In ‘Fair Margaret and Sweet William’, stanzas balance each other, dialogue alternates between speakers; and there is progression in both time and place. In ‘William and Margaret’, the marriage to another woman is not depicted at all, action is at a minimum, and speech takes the form of extended declamation rather than dialogue.

What’s more, Malloch wasn’t a popular guy. Samuel Johnson said Malloch had personal motives that were “mercenary and his literary work [was] forgettable.”8)William and Margaret”: An Eighteenth-Century Ballad by the English Folk Dance and Song Society, The Free Library. In 1880, William Chappell accused Mallet of out and out plagiarism.

Both ballads appeared in several broadsides back in the day. They also appeared in anthologies. “William and Margaret” appeared in Allan Ramsay’s 1740 Tea-Table Miscellany: or a Collection of Choice Songs, Scots and English. “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” appeared in Thomas Percy’s 1775 Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (I believe 2nd edition.).

The ballad has changed throughout the centuries to fit the region, times, and/or singer. I’ve come to find that’s how most ballads work. But the core of the story is still there. Francis Child lists three versions: A, B, and C. In Appalachia, the song follows all three of these in some form, though the scene where William and Margaret talk on the hill is dropped for the most part. The British Traditional Ballad in North America by Tristram P. Coffin attests that several types of the ballad “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” exist: A, B, C, D, E, F (and maybe more). The bullet points below give examples of these differences:

-

“Fair Margaret and Sweet William” from A Book of Old English Ballads, p. 71 Sacred Texts.com A —– The ballad begins with Sweet William dressing in blue, spurning Lady Margaret, and digging the proverbial knife in deeper when he tells her she’ll see him marry someone else. The rest of the story is the same as in my summary.

- B —– Everything is the same except Margaret throws herself out the window and dies.

- C —– The difference here is William’s new wife has the dream instead of him. She tells him about it.

- D —– Everything is the same except “She has her mother and sister make her bed and bind her head because she feels ill. She then dies of a broken heart.”

- E —– The difference in this one is Margaret is alive at the foot of William’s bed.

- F —– Margaret’s ghost comes to the foot of the bed and “blesses the sleeping lovers before going to the grave . . .”

Some believe the versions “share similar lyrics and themes but most of them are different enough to warrant being completely different songs.”9)“The Ballad of Lady Margaret and William: A Story History with Song Lyrics” World Turn’d Upside Down Yet, a ballad works its way to differences like a ladder. One step builds on another until it becomes what it is. As Britannica notes:

. . . the first recording of a ballad must not be assumed to be the ballad’s original form; behind each recorded ballad can be one detected the working of tradition upon some earlier form, since a ballad does not become a ballad until it has run a course in tradition.

The song still inspires singers and musicians. Even Canada has a version. Like most ballads, “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” was an oral tradition in England, Scotland, and Ireland. But in America, it has staying power. Most, if not all, sound recordings of the ditty have been made in America. Pete Seeger included it in two albums: his 1957 Folkways album, American Ballads, and Columbia live album We Shall Overcome: The Complete Carnegie Hall Recording 8 June 1963. Seeger said of the ballad:

This ballad was one of the first I ever learned, in 1935, from the country lawyer and old-time banjo picker of Asheville, North Carolina, Bascom Lunsford. My thanks to him. It is a medieval vignette, and the last verses describing the conversation between Lady Margaret’s ghost and her false lover are as close as we get to superstition in this LP.10)“Fair Margaret and Sweet William” Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music

Singers from the Wildgoose album Return Journey noted:

One time when visiting the Roaring Forks section of Madison County, N.C., I heard little nine-year old Alice Payne sing this song, just as given here. She had learned it from her mother and grandmother and had never seen a written copy.11)“Fair Margaret and Sweet William” Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music

So, our trail has led us back to where all ballads begin: the oral tradition. The aforementioned little girl learned the ballad through her matriarchs’ singing. Thanks to various broadsides, collections, and anthologies, we have been able to share these beautiful poems and songs with the world.

Bonus — Click on the singers below for renditions of “Fair Margaret and Sweet William.”

Sources (in no particular order):

- Broadside Fair Margaret’s Misfortune or Sweet William’s Frightful Dream on his Wedding Night – Imprint: S. Bates, London Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Libraries

- Broadside Fair Margaret’s Misfortunes; or Sweet William’s Dream on his Wedding Night -Imprint: Aldemary Church Yard, London – Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Libraries

- The British Traditional Ballad in North America by Tristram P. Coffin 1950, The American Folklore Society.

- “Fair Margaret and Sweet William folk ballad” Britannica.com

- “The Ballad of Lady Margaret and William: A Short History with Song Lyrics” by World Turn’d Upside Down, April 12, 2010.

- “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” from Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music

- “Sweet William’s Ghost: A Deadly Ballad” from Kat Devitt: Turning Tragedy into Timeless Romance

- “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” from The Child Ballads: Ballads from the collection by Francis James Child as rendered by various performers

- The Tea-Table Miscellany: or, A Collection of Choice Songs, Scots and English in four volumes by Allan Ramsay, 1740. Internet Archive.

- “Margaret’s Ghost” by Gwen Raverat, 1909. The Raverat Archive

- The Knight of the Burning Pestle by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher. ed by Murch, Herbert, 1908. Library of Congress

- https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/3853/Knight_Of_The_Burning_Pestle.pdf;sequence=1

- English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child; Helen Child Sargent; George Lyman Kittredge, 1904, Internet Archive

- “Lady Margaret” from Barry Taylor on Contemplator

- “Fair Margaret and Sweet William,” Wikipedia

**Featured image: 1785 William and Margaret by Joseph Wright Derby from Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry – Google Art Project, Wikimedia

References

| ↑1 | In some versions his bride is described as “brown” or “nut-brown.” Way back when, these were derogatory terms for a “plain woman, that could also describe a sallow-skinned or sunburnt woman.” With a little guesswork, and with a smidgen of knowledge of the times, one might say he left Fair Margaret and married for money and acreage. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Some versions say “high hall door,” or “high hall chair” instead of window. |

| ↑3 | The ballad is also known by “Lady Margaret and Sweet William.” |

| ↑4 | Beaumont, Francis, and John Fletcher. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. ed by Murch, Herbert S New York, H. Holt, 1908. Library of Congress. ii, 8. |

| ↑5 | Beaumont, Francis, and John Fletcher. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. ed by Murch, Herbert S New York, H. Holt, 1908. Library of Congress. iii, 5. |

| ↑6 | Most versions have “harm” instead of “loue”/ love. |

| ↑7 | English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child; Helen Child Sargent; George Lyman Kittredge. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Co. 1904. p. 157. |

| ↑8 | William and Margaret”: An Eighteenth-Century Ballad by the English Folk Dance and Song Society, The Free Library. |

| ↑9 | “The Ballad of Lady Margaret and William: A Story History with Song Lyrics” World Turn’d Upside Down |

| ↑10, ↑11 | “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music |

Your research is exceptional! I am impressed. I really enjoyed listening to all the recordings. It was hard to pick a favorite, but I am going to say the simple rendition by Sheila Kay Adams is my first choice. Thank you for a great post!

Thank you, Peg! It’s certainly a difficult choice. Adams is my first choice, too.