Here in 2020, odd year it is, we’ve canceled everything. Like the rest of the world, our usual day by day is not our normal day by day anymore. Today is kind of an odd one, though, because I’m on the road. I’m taking a mini vacation of sorts. To get out of the worrisome, civilized world, I’ve taken hikes. The exercise has helped me manage the past few months. I’ve been spending a lot of time in the Smoky Mountains, and a few state and local parks here and there. Just a week or so ago, however, I received an email from a writing buddy of mine, Tom Anderson. Tom recently published a piece, The Battle of Kings Mountain October 7, 1780, at our online writing hub, Appalachia Bare, regarding the Battle of Kings Mountain – a Revolutionary War battle in South Carolina. In this fight, patriot militia defeated British loyalists led by the famed British Major Patrick Ferguson. The battle is considered a turning point in the American Revolutionary War, one of utmost importance for American independence. Tom shot me an email after his piece hit the internet to see if I’d be interested in traveling to Kings Mountain National Military Park to write about the natural history of the place.

When I read Tom’s email, I got excited. Why not take a day trip somewhere new? Been awhile since I had some solo time on the road. As lonely as 2020 has been so far, the year is lonely in an odd way. “Social distancing” is the motto said repeatedly this weird year. Thing is, we are not socially distant at all. We are more connected than ever before by phone, email, social media, video conferences, and a list of apps that seemingly never end. We’re bombarded by news, media, and noise constantly. Socially distant is not what we are at all; we are physically distant. Perhaps the weirdest part of pandemic life is missing people, even though we communicate with them more than ever. We wonder when we can physically be with our loved ones again. All our constant communication somehow makes this feeling even worse – we miss the quiet, still presence of physical people.

So, here I am, alone on the open road, away from the news and apps, driving mostly in silence, occasionally listening to music, or checking in on the New York Times 1619 podcast, but I’m mainly stuck in my own head.

Where do the thoughts wander? America, that’s where. Where are we going, America? A hard reckoning needs to fall across all of the country, across all national history, across all belief systems, all institutions, all ideas of liberty and freedom. A new civil rights movement is here – challenging the legitimacy of American institutions past and present.

This is a lot of fodder for the three-and-a-half-hour drive that takes me out of the Tennessee Valley, across the Blue Ridge province, and on into the low, rolling hills of the South Carolina Piedmont. Typically, when I think of South Carolina, I think of coastal cities, marshes, and wetland. Though the Piedmont is a large, low lying province, the geologic area is still a temperate Appalachian Mountain biome. Today, in Kings Mountain National Military Park, I’ll hike across the Neoproterozoic Battleground Formation. The terrane consists of explosive volcanic rocks that have been crushed and baked, metamorphosed past their igneous origins. White, gray, and blue hued plagioclase clasts lay with quartz phyllite and sheet grained schist. Volcanic conglomerates and ancient magna rocks round out the matrix.

Though some of the surrounding vegetation – dogwoods, beech, hemlock, to name a few – are recognizable, I know I am out of my neck of the woods. The unique metamorphic geology here, coupled with the hot and humid climate, produces an ecosystem that is eerily familiar, but strange all at once. Extensive oak, hickory, and long pine forests are in abundance. They speckle a land of intermittent, isolated prairies and grasslands.

I am grateful for this experience, in all its oddity, in our Appalachian region. I am grateful to be away. During the pandemic, hell, because of the pandemic, I broke the norm for a day. Today I’ll just live and play. Perhaps I’ll get the chance to flirt with danger and explore a forest I’ve never thought of walking through before. My gratitude reminds me of an old John Muir quote: “Thousands of tired, nerve shaken, over civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home, that wildness is a necessity.” So true.

After tying my boots and strapping my pack on, I look around the scarcely populated parking lot. A handful of folks are out here on this beautiful, hot, day, but most of the parking lot is bare. Eyeballing a nearby map and information board, I see the Battlefield Trail is a self-guided walk that clocks in at only one-and-a-half miles. Cool enough, the trail will have numerous exhibits along the way describing the battle, but I didn’t drive all this way for such a short stroll. Luckily, there are some other trails in the area for me to disappear on as well.

The Battlefield Trail is paved and well maintained. Once under the canopy, I can do nothing but enjoy a warm, whispering breeze and admire the full green leaves of white-oak, red maple, and tulip poplar against an intense blue sky decorated in a parade of cotton white clouds.

Though paved, the trail bends and meanders, and, in places, rises only to fall steeply. Though the canopy shades my flesh, and a pleasant breeze is constant, the July afternoon is hot and thick with humidity. Sweat pours out of my skin like condensation on a cool glass. In the words of American Journalist Russell Baker: “Ah, summer, what power you have to make us suffer and like it.”

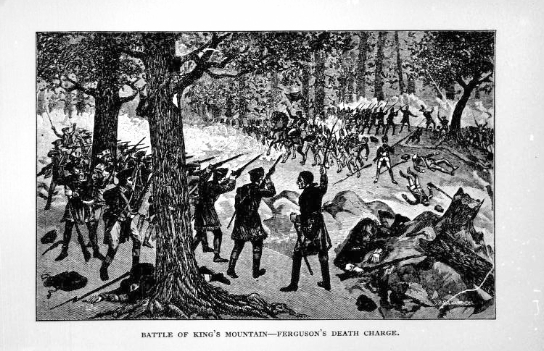

Along the way, I’ve learned a good deal about the battle that took place here back in October of 1780. The fight was fierce and fought completely by Americans – patriots against loyalists. For one hour, rifles cracked, and blood spilled. One-thousand men stood on each side. In the end, the patriot militia defeated those recruited by the British army. The American victory here was referred to by Thomas Jefferson as “the turn of the tide.” The shooting let loose precisely, and at close range, as men moved from tree to tree to climb a rock-strewn ridge where both Major Ferguson and British hopes for a Southern victory would end up dead.

I move in a second-growth forest. European expansion came to most of Appalachia after the Revolutionary War and the mountains experienced intense logging that leveled a centuries-long primeval forest. When this battle was fought, the old and true titans of oak, hickory, and chestnut covered the slopes of Kings Mountain. These titans stood much farther apart than today and were as wide as pick-up trucks. Presently, numerous understory plants abound, but, before the great European logging, hardly any underbrush, save for some possible ferns that would’ve appeared giant-like, decorated the understory. This landscape created an environment where those in the fight could see their enemies at long distances, run free of obstruction, and signal their brothers in arms to continue shooting and bayonetting. At the time of the battle, the top of Kings Mountain was completely bare.

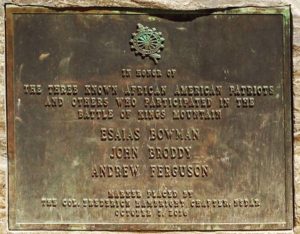

I read a lot today about the battle. Information booths litter the trail so travelers may take themselves on a guided history tour. I read about “local boys” and “spies”; I read about the rifles the patriots used, and how they gave the militia an advantage over the burdensome muskets of the loyalists; I read a lot of names, biographies, and interesting tidbits of information. That said, one particular memorial especially catches my attention. Climbing the path towards the top of the mountain, a couple hundred meters from where a giant monument for the battle resides, a smaller, humbler monument gives remembrance to Esaias Bowman, John Broddy, and Andrew Ferguson. Above these three names, the words “In Honor of Three Known African American Patriots and Others Who Participated in the Battle of Kings Mountain.”

This memorial strikes me for two reasons. As I stated before, we are, at this time in our nation’s history, witnessing popular momentum within the civil rights movement. Protests and civil unrest are everywhere in a politically divided and pandemic-torn nation. The ongoing struggle for social justice this year has brought much needed attention to racial, class, and even environmental disparity. Black Americans and their allies have sparked a wave of protests against state violence and systemic racism. Second, I get to thinking: During all my hikes through the wilderness of national parks, I can’t recall ever having seen another memorial, a single information booth, or even a pamphlet, regarding the Black American experience in natural lands. This revelation brings me back to that hard reckoning our country needs across all her histories, institutions, and beliefs – and this reckoning must also include the great preservationist and conservationist ethics that protect the land, rivers, lakes, and seashores for all current and future generations.

Time to revisit that aforementioned John Muir quote – the one about “thousands of tired, nerve shaken, over civilized people” discovering the mountains and wilderness are “home.” The “home” and “wilderness areas” Muir speaks of were not originally intended for all current and future generations.

I would argue no single person is more important to the history of environmental conservation than John Muir. The geologist, naturalist, and author holds many titles – the “wilderness prophet,” “patron saint of the American wilderness,” and “father of the national parks.” Along with his famous movement for parks, Muir is the founding member of the Sierra Club – the nation’s oldest conservation organization. This is an upstanding legacy, and, to be honest, Muir is personally one of my favorite historical figures. All of this said, I’ve recently come to my own reckoning with Muir’s legacy after learning more about the man I’ve held in such high regard most of my adult life. I now attribute an important and pervasive part of his history with a real, long-lasting equity gap that exists in wild lands. This equity gap persists despite rhetoric that seems to assure otherwise. This social problem is understood through the historical lens of systemic racism, the forgotten (or, more likely, ignored) history of environmentalism, and the disturbing ethics that built the preservationist movements of the early 20th century.

In an article for The New Yorker, “Environmentalism’s Racist History”, Jedediah Purdy, a law professor at Columbia University, maps a troubling story throughout 20th century environmentalism. The early preservationist movement worked for a means of escape from the hum drum of life in cities, towns, neighborhoods, and in their place offered natural places, as Muir famously wrote, “to see the face of God,” in the high country. With investigation, however, this “escape” is not as innocent as it appears on the surface.

A close examination of the writings of Muir and his counterparts – Gifford Pinchot, Madison Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, others – reveals ideas that are not simply prejudiced, but racist – especially in regard to Black and Native Americans. Muir’s less popular essays are full of racial slurs and epitaphs. Most early conservationist writings by Muir and others were penned to ensure white followers they would not be bothered by nonwhite people in national parks. A special identity was placed on parks – an “escape” for wealthy white people, a place of solitude from the poor, the weird, the fragile. An “escape” from “the others.”

Some folks may try and disregard this unsettling truth as the “ordinary” or “casual” racism of the time, but the cascading effects of institutional racism advocated by these men are still felt today. Wilderness ethics, and the politics these ethics engage, expands the boundaries of moral concern to all the flora and fauna within natural lands. In early preservationist history, though, nonwhite people were excluded from this vision. In his article, Purdy reminds us that the time in which these men lived is part of an explanation for this exclusion, but is surely no excuse for the idea that nonwhite people are not only lesser humans, but lesser moral agents than standing forests, rolling desert hills, the open prairie, surviving wildlife, rambling waters, and the rocks of which mountains are made. Our early environmentalist icons, their descriptions of nature, their arguments for preservation, the identities tied to the land itself, are constrained. Muir’s naturalism awarded him a refuge from his idea of civilization. For Muir, and others in the early movement, their writings ensure, Purdy argues, that “working, consuming, and occupying nature was a way for a certain kind of white person to become symbolically native to the North American continent.”

As the new civil rights movement rises, as Confederate statues fall across the south and the rest of the country, those of us in the environmental movement concerned with species conservation and a new preservationist ethic, need to have a reckoning of our own – our own “statues” need to fall. Our national parks, our wilderness areas, largely tell the stories and intricate histories of white Americans. Most visitors to parks and wilderness areas are white. And the National Park Service, romanticized by Ken Burns as “America’s Best Idea,” is one of the least diverse agencies in the federal government. Systemic racism has bled across our wildlands. Our parks are spaces of freedom and absolute liberty – for some, but not all.

The park system, traditionally, has paid very little attention to the history, stories, and conflicts of people of color. This very lack of diversity and representation raises a significant risk: The demographics of the United States are changing. Soon, the parks and their stories may be irrelevant to most of the country’s population. The United States Census Bureau projects people of color will be the majority of Americans by 2044. The stories told by parks and the people who visit should, and need to, reflect the diversity of the nation. When communities are not represented in park history, and their stories are not tied to the land, an existential crisis exists. The parks themselves, just as land, water, and air, are resources to be preserved. Wildlands are at risk of exploitation. Democratic movements will always have to raise money, stand, and engage the politics of wilderness. But why care for wildlands if one cannot see themselves in their stories?

Luckily, several leaders within the agency are addressing diversity issues. In the cherished Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Cassius Cash, one of sixteen Black superintendents of the Park Service, requires diversity in applicant pools for all new jobs. In a story from Environment & Energy Publishing (E&E News), Cash is quoted: “I take that so seriously that every permanent position in this park is presented to me and my deputy.” Cash then added that diversity is now regarded “as an asset rather than a liability.” The Great Smoky Mountains are America’s most visited national park, a fact of which Cash is proud. But the superintendent is quick to remind us the future of the National Park Service will be determined by who visits the parks, not by how many. Cash explains at E&E News:

This world looks different, no matter how you want to cut it or slice it. If we do not want to go into extinction, knowing that eighty percent of the population now lives in urban areas — if we don’t reach out or mirror the folks that live in those communities — we cannot be ‘America’s Best Idea’ in the next fifty to sixty years.

To keep the parks in the mind of the body politic, they, like all institutions, need to be more inclusive – more representative of the whole. Essentially, the park system, whether large expanses of wilderness or simple monuments, record the nation’s history. Non-white voices deserve, and are long past due, their amplification in these spaces. Cash’s leadership in the park is a blueprint for the entire system. He’s traveled the Smokies to collect oral histories, personal experiences, and family adventures of Black and nonwhite Americans across the political boundaries of his park. This important endeavor will create exhibits, educational programs, and even lead to print publications.

Assisting this effort, is Black American PhD student Adam McNeil. I first heard of McNeil – a Rutgers University graduate who initiated the research project, “African American Experience in the Smokies” – while listening to a “Black in Appalachia” podcast. McNeil’s work has brought him all over the area surrounding the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. He’s conducted oral histories, located individuals with archives, dug through forgotten historical records, and more. In essence, his work helps people, all people, see themselves in this ancient wilderness corridor. He seeks to tell the comprehensive stories of all people, so that all may feel accepted and appreciated.

In addition, Black American native of Harlan County, Kentucky, Dr. William H. Turner, who holds a PhD in sociology and anthropology, specializes in race relations. He finds the work of amplifying black experiences in the region critical to the whole story of the Appalachian Mountains. Black people were not just servants, slaves, and butlers in the South, they were some of the first immigrants to the region. In a print interview for Sha-Conage, a newsletter produced by Friends of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Turner tells us:

The first black Appalachians, indeed the first Africans in the Americas, did not live as enslaved persons under the control of white plantation owners, railroad builders, or mine operators; instead, they lived, starting as early as 1526, within the domain of the Cherokee Indians. They had come with Spanish explorers and conquistadors such as Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon and Fernando de Soto. Some of them fled and went into the mountains to live with the Indians. They were in the center of the spirit at Kituwah, near Bryson City, North Carolina. Isn’t that as Smoky Mountains as you can get?

Recognizing and actively telling the stories of a diverse Appalachia is paramount in telling a whole, official history. And this complete history may just save the region. Cassius Cash, in his interview with E&E news explains: “I think the true long-term success (of the Park Service) comes in ‘the who,’ and that’s what I want to focus on.” Cash’s words bring me right back to that Muir quote, that wilderness is a “necessity.” Muir is half right. The future of preservation is dependent upon a diverse, multi-cultural, coalition. Civilization needs wilderness, but wilderness also needs civilization.

I want to share parks with everyone, so I can learn from everyone. I don’t mean the simple visitors, those who have no respect for nature, who will “meadow stomp” and pose for pictures with bears. No, I mean all should be able to know how to love, respect, and experience their open spaces. Wilderness areas are, for me and many others, spaces of liberty. I hope everyone has a chance to learn and love these Appalachian hills and all wild spaces. I am under the impression that the human animal cannot know freedom without wilderness. We need spaces beyond our cities, neighborhoods, highways, and byways. Everyone deserves the chance to simply run free, where children and adults can live, even if just briefly, absent of control or domination from the Leviathans of human civilization. As we grow a 21st century environmentalism, I hope we keep in mind that every piece of wilderness saved, from sea to shining sea, is a place of leisure, danger, solace, connection, and individuality saved for play and human freedom.

**Featured Image from Wikimedia