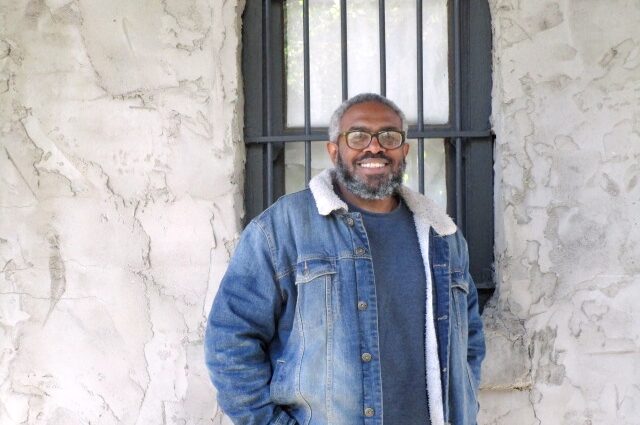

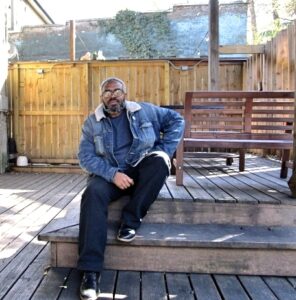

Near the tail end of 2023, Appalachia Bare had the great honor of interviewing Knoxville, Tennessee’s Poet Laureate, Joseph Woods, aka Black Atticus. The esteemed Woods is a hip-hop artist and spoken word poet who weaves words into a tapestry of storytelling and poetry. In 2013, he co-founded Good Guy Collective, a community that encourages and inspires artists to create music through hip-hop. Joseph founded Po’Boys and Poets, “a monthly open mic featuring guest spoken word artist storytellers & songwriters.”

He once imparted, “Word is fire,” to young writers at a workshop presentation.1)The workshop was from an event for Pellissippi State’s Young Creative Writers Workshop Webster’s Dictionary says the word “fire” has some of the following definitions:

“burning passion; liveliness of imagination; brilliance, luminosity;

a rapidly delivered series (as of remarks); to give life and spirit to;

to fill with passion or enthusiasm; to light up as if by fire; to propel”

That bit of wisdom illustrates Joseph’s awareness, skill, and passion for words. His writing is poignant and his spoken word is powerful. Appalachia Bare is pleased to present the following interview with such a creative, phonological bard. The transcript is an edited version with most of the filler words, repetitions, and interruptions removed. The written interview has two parts. Part one appears below, and you can find part two of the transcription here. Enjoy the unedited audio version below.

![]()

Black Atticus

AB: So, the questions that I have, you’ve probably been asked a thousand times. But, I tried to choose things that were about poetry and spoken word. What is your opinion, what do you think the purpose of poetry is?

Atticus: Ooh, the purpose of poetry. Oh, gosh. I’ve never been asked that question. [Laughs] I’m sure that it’s many definitions on this one. I feel like it’s a way to enhance the frequency of language. I feel like it’s a, it’s a dance, right?

I mean, ‘cause you just say it and then thus it’s a sentence. I think that’s, for me, that’s the purpose of it, right? ‘Cause when I study it beyond like emotionally what it does, I do feel like poetry helps you connect with yourself, connect with healing, connect through things or express yourself. I mean all those things we already know, but I think practically, as far as function-wise, you know, I think it just helps increase the frequency.

AB: Do you think spoken word furthers that purpose?

Atticus: Oh, mmm, it can. It can. I wouldn’t say that it does it more so than any other form. Um, it does depend on the presenter’s skill level, right? Yeah, because I’ve been blown away by some stuff and never heard the poet speak at all.

Atticus: Oh, mmm, it can. It can. I wouldn’t say that it does it more so than any other form. Um, it does depend on the presenter’s skill level, right? Yeah, because I’ve been blown away by some stuff and never heard the poet speak at all.

Like, especially Langston. A lot of his work blew my mind. Still blows my mind. I was not blown away when I heard a recording of him though. Oh man, I wish I’d never heard it. Yeah, oh man. [Laughs] It sounds so much cooler in my head. [Laughs]

AB: What do you think is the most important element of a good poem?

Atticus: Oh, um, uh, it’s ‘set up and spike,’ right? You know, like, how do you get me to understanding? So of course, clarity, enough clarity to be understood or enough clarity, uh, even if it’s vague. Give me good words to interpret with, you know what I mean? So the way the words are used to, to bring the reader or the listener to understanding.

So the journey, the journey of it is a good thing. And I call it ‘set up and spike.’ Yeah, that’s my thing.

AB: Do you think—first of all, you are a poet.

Atticus: Yes.

AB: Do you consider yourself more of a spoken word poet?

Atticus: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, you know, I went from rapper, then poet, right? And now writer, like for me, it was in that order. And I feel like, just like with hip-hop, uh, usually with the lyricists, you either start off freestyling or you start off writing. And the goal is to get to where we can’t tell which one you’re doing. Like, did they write that down or make it off the top of the head? Like, you know, finding that blend. And so the same thing, I think, with poetry, at least with the introduction of spoken word, I think a lot of us were emphasizing the performance.

Emphasizing like saying it aloud and not so much concerned about how it read. Because a lot of slam poetry doesn’t work on paper. At all. Just like a lot of page poetry does not work on stage, right? If they can’t read what you’re doing, they’re going to miss some of the nuances, right? So I feel like mastery is getting to that middle point. That’s my goal, yeah, like I want you to be able to almost see it, right? See it as I say it out loud. But for me, yeah, I started off out loud before actual writing.

I’m just now at the point where I feel like this is ready to be on page. And printed. That’s how much I revere actual written word.

AB: What role do you think social media plays in the world of poetry today?

Atticus: Hmm. Well, I think it plays a vital, propelling component to poetry, especially spoken word poetry. But I’ve seen it work out for writers too, just taking snapshots of their poems and just seeing how . . . I think it’s helping to spread the message a lot faster, like 10 times faster.

Just to share some words and then watch it resonate, you know? I mean, we just now get to the point where spoken word poetry is finally being recognized, I think, at a Grammy level. As a separate entity from—‘cause they was lumping us in for a while with songwriters, right? With all writers. And no, it’s different. So yeah, I feel like social media played a factor in that, like when they can see the numbers and go, okay, there’s a lot of people who really, really like this. And so it’s getting the respect it deserves. I feel like social media is helping with that.

AB: What inspired you to write poetry from the beginning? I know you said you were a rap artist in the beginning.

Atticus: Yes, rhyming. Yes, rhymes. For me, it just started off with hip-hop, so the beat, the culture, the cool. I remember, you know, growing up in the South, during the 90s, during hip-hop, like late 80s, early 90s.

For me, it would have been early 90s, right? Coming out of the whole 80s era, loving Phil Collins, Prince. You know, the eighties were great. Hip-hop really took off around 90, 92, 93, really took off during what they call the golden era.

So I was fascinated with it, but all the voices were either from the West coast or up North. Most of them were from up North. So, it wasn’t until the South finally started having something to say, like, really, artists out of Memphis, uh, Playa Fly, and then you had, of course, Master P and No Limit. The South finally had something they were saying. I wasn’t necessarily crazy about it, but I was glad to go, ‘Okay, we got something.’ And then when Outkast was on, oh it was over.

So I think for me, when I got my hands on, uh, [chuckles] I laugh to say it now, but, uh, Biggie Smalls’ first album, and then also a group called Black Star, which had Mos Def and Talib Kweli. When I got my hands on those, something about hearing young men, you know, maybe ten, twelve years older than me at the time, and hearing them speak so intelligently and making it sound cool, like being nerdy was cool, right? So I was like, ‘Oh snap.’ ‘Cause I was a comic book readin’ super geek. So I was like, yeah, this is great.

It caught me at a time when I was already drawing comic books and making storylines. And because the comic books I was reading, uh, that’s what got me into language in the first place. My uncle Ronnie had given me all his comic books from his childhood. Right? So these are printed before I was even born, but man, the writing was so much more dense.

The writers at that time, we’re talking 60s, 70s, maybe late 50s too. The writers just had a more extensive vocabulary. I was always looking up words anyway, ‘cause I wanted to understand what Conan was going through. Like, what was he going through, you know? [Chuckles] And so that had me fascinated.

The writers at that time, we’re talking 60s, 70s, maybe late 50s too. The writers just had a more extensive vocabulary. I was always looking up words anyway, ‘cause I wanted to understand what Conan was going through. Like, what was he going through, you know? [Chuckles] And so that had me fascinated.

Then I remember hearing Talib Kweli on a song where he said, ‘Are you stopping us? It’s preposterous, like an androgynous misogynist.’ And I was just like, what did he say? What? So that was the first time spoken word had actually got me to want to go back to the dictionary. Usually, it had only been comic books.

And so, I said, dude done said some stuff, I don’t know what it was. And I was like, okay, cool. So we can do these things. And I think it was a way of tapping into the genius. And I’m sorry, my answer is going all over the place. [Laughs]

AB: Oh, no. You’re fine.

Atticus: Then of course, when I heard Biggie Smalls, uh, he was, no pun intended, he was notorious for saying more with less. It was the first time I’d ever heard like over half the dudes in my neighborhood broken down into a fragment sentence. He was so good at that. Yeah. This is a short sentence. I was like, oh man, he just summed up everybody in my neighborhood. How’d he do that? I thought it was powerful, so I got addicted to it. I wanted to learn how to do that.

AB: Do you see yourself as more of a storyteller or a wordsmith?

Atticus: Wow. A wordsmith growing into a storyteller.

AB: Oh, oh, wow, that’s great.

Atticus: Yeah, ‘cause the art, that’s how we are. I mean, as a songwriter here in this city, doing hip-hop, I realize that it’s all folk music. Right? It’s all folk music. We’re all just telling the stories about where we’re from, or a perspective. But the actual art of storytelling, yeah, I’m most fascinated with that, and, according to my crew, my stronger rhymes are the stories.

AB: Um, how often do you practice and how long does it take you to . . .

Atticus: Ooh. Man. Uh, well, first off, I don’t practice as much as I should. Not as much as I should. If I, if I was actually disciplined, I’d be practicing three to four times a week. If I were disciplined, right?

AB: [Chuckles] Who is?

Atticus: Who is? Nah, I mean, I have some new material that I’m going to be releasing. So I will be practicing that. I guess once it’s crystallized completely into this reality, then I will be practicing that a lot. But some stuff I’ve been running so long, so I’m trying to think, at the height of it, I guess when we first started, we’d be practicing two, three times a week, if it was slam. For hip-hop music, we would do at least two rehearsals before the show, day of, if we can, right? Just run it, run it, run it again until we felt like it was solid or whatever. Um, but yeah, looking back now, I don’t, I don’t practice as much as I should and I know practice makes perfect.

AB: What were some of the initial obstacles you faced when starting your career as a poet, and how did you overcome them?

Atticus: [Laughs] I think, I think it would be realizing there was a career. [Both laugh] That might have been the initial thing.

Um, well, just for any creative, especially an art that involves being on stage or being in a crowd, I think your biggest obstacle is getting your art recognized as work, right? ‘Cause if you look at how many ways you use the word ‘play.’ When you play again, can I play a new song, can I play, and play is the polar opposite of work.

And so, yeah, getting that art recognized, that this is work, is most creatives’ challenge. And I think what a lot of young creatives are, just artists starting out, no matter what your age is, ‘I want to do this professionally,’ right? Getting paid for something you’ve never been paid for before is a hard thing. Is it about holding a straight face when you say your price, knowing your worth, your value? How much is that? You know? And of course, starting off, it was just like, yeah, sure. We’ll go, we’ll do it. I’ll show up. Sure! You know, [Chuckles] just all over the place.

And then, you start realizing, given a crowd and an audience, that energy, no matter what’s going on in your world that day. Really starts to feel like work. Like, ‘Oh, I got a clock in, right? Oh, I got a clock in and give it. Yeah.

And so, for me, that’s been—not just for me, but also for some of my peers too—is realizing the value of our work and then how to approach the market with it.

And I think it is getting to that first ‘no.’ Right? For something you said yes to for so long. But in some aspects, I was lucky that something about the level of presentation or whatever, they were setting the price or they recognize like, ‘Oh, he’s not just gonna come through for free.’

I remember I did a show at Knox Ivy with Kelly Jolly and um, uh, his first name was Samuel. He was a musician. It was me, Kelly Jolly, and Samuel.

Anyway, we performed at, uh, Knox Ivy one time, and once we got finished, I heard them whispering, ‘Oh, we want him to come back. Oh, but what’s he gonna charge for it? It’s probably gonna be like 2,000. Or like 1200, something like that.’ I was just like, Huh! It should be! [Laughs]

But that was more than anything I’d ever charged. It made me think, like, why am I not charging that? Yeah, so, it’s different, I think, for young artists if they have mentorship. Um, I wouldn’t have, this is strictly for my solo work, but I did come up under Linda Parris-Bailey in Carpetbag Theatre, and Linda always emphasized that artists get paid. Period. She was the first person to put a check in my hand for the work I was doing. And at that time, I was helping to write a play called Swopera with Carpetbag Theatre as a young artist. So I’m like 19, 20 years old.

And so she put that first seed in our heads, right? Artists get paid. But then, as I branch off, it took me a while to, you know, you kind of go back and remember those lessons like, wait, wait, wait, I should be getting paid per diem. I should be getting paid, performance separate and lodging, all the things that anybody else can get paid. And yeah, of course, when I was like, what, nineteen, twenty, I thought she was nuts. Until she cut a check.

Yeah. Yeah. But she also shows, which is why I’ve only performed in one play. Oh man. That’s a whole nother animal, man. [Laughs]

I mean, they were blocking. It’s acting. It’s dancing. It’s singing. It’s everything! And then, as much as they rehearse, oh no. I would need to get paid, paid. I can’t. You gotta love it, man. I didn’t love it that much. [Laughs]

AB: Can you share an experience where you felt particularly rewarded or, um, satisfied as a poet?

Atticus: Ooh. [Pauses] I mean beyond the city of Knoxville voting me as poet laureate, that’s one for sure. That’s a road I didn’t know I was on.

AB: That’s beautiful.

Atticus: Yeah, I was blown away with that one. And then to find out that they’ve wanted me to be this like years ago, they were wanting this to happen.

I feel like it took, it took Rhea’s2)Rhea Carmon: Knoxville’s Poet Laureate 2020-2023 term for them to really get an idea what they were actually asking for. Rhea was a great blend ‘cause she’s also on page and she hits the stage. She’s both. And I feel like them going, ‘Oh, you know what? Spoken word’s pretty powerful. Let’s go ahead and get him.’ I think that was a great handoff. I think they needed that. [Chuckles] Yeah, it worked out great.

But anything else as far as the most satisfying things I’ve ever had with open mics and with poetry, um, with slam, I feel like I can still feel that energy in the room, and the first time they get to stand up and say what they have to say uninterrupted, completely uninterrupted. And then, to know an audience is, is actually listening, right? I think that’s therapeutic on a level that, you know, it probably hasn’t been studied enough. At the same time, it’s like I’ve seen a mother and daughter hug for the first time in years, ‘cause somebody got up on stage and said that thing that nobody’s saying in the family and just said it out loud. So, um, poets of mixed ethnicity, you know, they usually have to come to terms with that and say it out loud too. Some of the most powerful pieces I’ve heard have been, you know, people working out pains.

AB: Have you ever found any of your projects or performances particularly difficult? Any that you’ve ever found to be difficult or challenging?

Atticus: Woo. Not as they’re going to be. So far, I’ve been pushing myself to write, uh, closer to home. And I want to say, um, no. No. Naw, I think not yet.

AB: I think everything’s a challenge, really, if you think about it.

Atticus: It is. I have writers, though, that blow my mind with how brazen they are. How vulnerable they are. And, uh, I’ve been really good at tapping into emotion, and I can tap into frequencies that people resonate with, but I’ve still kept extremely private. There’s certain topics I’ve never talked about. I’ve never talked about my sex life. I’ve never talked about my traumas, at least not at length. I usually use a character, which is really what took off mainly, when I had characters like Langston Washington Carter, a poem based on a pompous professor and a college owner that I had when I was going to Nossi College of Art in Nashville.

I got Sergeant Six Weeks. Everybody loves the sergeant, the drill sergeant, but it was through these characters I was actually able to talk about the things that I actually wanted to speak on. I just couldn’t think of a more clever way to do it.

But the next work I’m putting out I’m going to be telling the story of growing up in Park City and I’m going to be addressing some traumas that I’ve never talked about. So that’s going to be probably the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. And I was inspired by my cousin Bush, his last project and working through Shape-Up, with him. Actually, all these albums we’ve been working together on.

But the next work I’m putting out I’m going to be telling the story of growing up in Park City and I’m going to be addressing some traumas that I’ve never talked about. So that’s going to be probably the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. And I was inspired by my cousin Bush, his last project and working through Shape-Up, with him. Actually, all these albums we’ve been working together on.

And then Rhea. Rhea just did her one-woman show, When a Teacher Breaks Free, so watching those two kind of put the stamp in it. So yeah, I can’t wait. [Chuckles] I’m already two albums ahead, so the next one I’m going to do is really going to be like a reconnection.

Just a reconnection with the audience for a minute. But I’ve never talked about things that happen behind the scenes, off the mic. And, uh, a lot of pushback that I get. Just like anybody else does. I mean, sometimes, you know, if you got, if you got family, it ain’t always perfect. And it ain’t always as supportive as you think it’s gonna be.

AB: Right. And, and, kind of like, how dare you air out our dirty laundry.

Atticus: Yeah, yeah. You know, it’s funny, I don’t have interest in that. I’m going to air out things I don’t think even they know ‘cause I’ve never talked about it. I’ve always chosen this route of like, I’m not afraid of conflict at all. I just don’t engage in conflict if I feel like it hinders progress, right? So, I’ll just move on. I’m sure any therapist worth their salt will let you know that what I’ve been doing is letting things roll off my back. I’ve never addressed things half the time. I just keep moving. It has served me, but it also has served me. [Chuckles] Right? Yeah, and it’s like that is something I don’t wish to proceed forward with. Like I said, I’ve watched people achieve healing when they’re doing it directly. I haven’t received that because I’m not doing that for myself. A lot of my poetry, my work is helping others. And I make it, I don’t know, it’s almost like, if you give advice to a person and sometimes that advice helps you too.

So, in the dialogue around the work, I receive more healing than I do from the actual, because I’m usually translating somebody else’s stories. I get a lot of examples. I think that’s why it works for people so well that like my work because I am listening to you, right? But, uh, this next work I want to get into is, uh, doing more listening to myself and then sharing that.

AB: More vulnerable.

Atticus: Way more vulnerability. Yeah.

AB: How often do you write?

Atticus: Not as much as I should. On my first poetry album, I got a poem called, “If I Wrote as Much as I Talk About Writing.” [Both laugh]

AB: I understand that.

Atticus: I do write a lot, though, more so lately. For the last few years, it’s been more songs. So much that it’s kind of hard for me to hear any kind of instrumental and not hear words. Yeah. If I’m not writing, I am recording. I have a ton of recordings on my phone, on my phones over the years. With songs, it’s not so much what you say it as it is how you say it. So you don’t want to forget how you said it. I’ve started getting more into doing voice recordings. Yeah. ‘Cause that’s, that’s just as crucial. That’s just as critical. And if you don’t say it the right way, it doesn’t resonate the same.

AB: Do you prefer to write by hand or on your smartphone or on your computer?

Atticus: Oh man. Uh, right now I prefer typing because it is closer to the speed of my thought. I love to write by hand, but, man, my mind goes, and I’d be feeling kind of like I’m dragging like, aaaah.

AB: [Laughs] Cramps.

Atticus: Yeah, cramps in the hands. Don’t get me wrong, in situations where the pen, okay, I can put it like this. It depends on the scenario, right? If I’m on a bus or a plane, or if I’m a passenger, I’m pen and paper. But if it’s a scenario where I got all my stuff and there’s a plug, I’m going to type it, throw some headphones on, or whatever.

For some odd reason, I really like writing in high elevations. So whether I’m in a really tall building, or whether I’m on a mountain, or whatever. High elevation. For some reason, I write like crazy. Give me a good view. I’m out.

AB: Oh, wow. I didn’t expect you to say that. That’s pretty wild.

Atticus: Yeah. I didn’t either. [Both laugh] One of my best friends, Carlton Star Relaford, took me to Kingsport for his family reunion. We get up there and they’re having the barbecue and, uh, and I hope they didn’t think I was being rude, but I couldn’t help it. The view and the elevation. I just grabbed a pen and paper, sat back, and started writing. That’s the first time I realized it. I was like, there’s something about being elevated. Yeah. Really does it for me. Really does it for me.

AB: In your writing process, do you plan each line, or do the words come as you write?

Atticus: Oh, both. I think it starts as a concept, and then the concept leads into that first line. Now, I don’t know where that line is going to be. Is it going to start? The middle? The beginning? I don’t know. That’s one way. I don’t use prompts as much as I should. I don’t like prompts. It’s the rare prompt that actually ‘prompts’ me to want to write. [Both laugh] Most of them are just like, oh man, why are we doing this?

AB: Yeah, it becomes genuine. But it seems in the beginning it’s just not. Because it’s not your—

Atticus: Yeah. But I think that’s also part of the exercise. I do want to give a shout out to storyteller Paula Larke. I met her through Carpetbag also. She’s a, yeah, she’s a legend. In the Appalachian circuit.

Linda had us, uh, at Highlander. Paula Larke was running one of her great, you know, get up and move around and sing workshops. Next thing you know, they were in a conga line. She had the whole room walkin’ around chanting something, and then she walks up to me and goes, ‘Hey, write me a poem real fast for this.’ And I was like, ‘okay,’ so I just, like, zzzzz. [Motions with hands] I whipped out something real quick, and then I started getting into, um, I ran across a book that I love so much, the War of Art by Steven Pressfield. And when I say I don’t do it as much as I should, it’s time to start doing those [prompts] because I have gotten to the point where I don’t wait on the muse anymore. I don’t wait to be inspired. Because if I did that, we’d never have any anything done.

But through that practice I have found that once you get started, the muse will find you. You just start and I have gotten more into that practice, which is cool ‘cause it got me back to the space of not worrying about making mistakes. I’m not worried if it’s going to be good. I don’t worry anymore if I’m ever going to share this.

But I used to do that all the time when I had sketchbooks. I was sketching stuff and it’d be crappy. I actually made notes about how much this drawing sucks. Like, you know, [Both laugh] I draw a character and make a comic bubble. Like I am drawin’ so poorly. It’s almost like I would just talk bad about it. But my thing is, letting that expectation go, right?

Because there’s nothing more personal, I think, than writing. Once you learn how to actually write, you’re literally doing it by hand. There’s nothing more personal than your signature. And so, yeah, you’d feel weird if somebody came along and grabbed your wrist while you were just trying to sign your name. It feels weird, let [inaudible] go. And I think it’s how we feel about prompts. If we’re waiting for inspiration, if we’re waiting for how, you know, how we do it.

Please visit us tomorrow for Part 2 of our interview with Joseph “Black Atticus” Woods.

**All images were taken at JACKS in downtown Knoxville, TN, photographed by Delonda Anderson

References

| ↑1 | The workshop was from an event for Pellissippi State’s Young Creative Writers Workshop |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rhea Carmon: Knoxville’s Poet Laureate 2020-2023 |