Over the last three decades since our summer community of Elkmont was wrested from our grasping fingers, we’ve had to watch other folks discover our “abandoned ghost town.” They find it while wandering around the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Out of nowhere it appears before them. Clusters of small, rustic cabins with big stone chimneys huddled around a large club house and swimming hole. It’s actually not hard to find if you’re looking. Just keep heading up from the river road. It’s right there, between the talking creek and the river’s roar. Careful in the mist.

Every time the “discovery” of our beloved Elkmont is made, there’s an outcry among us.

Abandoned? How dare they?

What will this idiot “discover” next—funnel cake?

FFS—this guy! Saying we didn’t know what we had.

I’m pretty confident in saying for the record that we knew what we had, we hung onto it as long as we could, and we’re overjoyed something remains.

But it’s not an abandoned ghost town—it just looks like one. And as the name has stuck, the upside is greater interest in what life was like in our lost community.

I can attest that our Elkmont was alive and well until 1992, when the National Park Service evicted almost all the summer families, with a few getting to stay a little longer. Elkmont was always about getting to stay a little longer. Another hour of hop-rocking in a pocket of sunlight, a few more minutes of kick the can as evening fell, one last ghost story by the fireplace before bed.

Elkmont’s life as a summer cabin community between the Little River and Jake’s Creek began in earnest in 1910 when businessmen from Knoxville began building rustic cabins for hunting and fishing. My great-great grandfather, Somers Ireland Van Gilder, was one of them building Cabin #6, “Dear Lodge,” now the Creekmore cabin.

Our firm grip on Elkmont first began to loosen in 1926 when the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established. Many among the summer families were all for the Park because it would put an end to the ravages of deforestation for lumber. But there were consequences.

The state of Tennessee condemned the Elkmont summer cabins asserting eminent domain over the use of the land. Summer families fought back, and a deal was struck. They could stay if they accepted half the cabin’s appraised monetary value as payment and signed lifetime leases. Payment for the cabin, but not the land. After their lifetime, they were out. To even the bargain a bit, families recruited their youngest to stretch out the term.

A little longer.

The strategy paid off in 1952 when the leases were extended to 1972 in exchange for the Sevier County Utility Company bringing electricity into the area. Without the summer families, there wouldn’t be enough customers to make the effort worthwhile. Thank you, sweet Jesus, my parents’ generation must have sighed, leaning back in their rocking chairs on the front porch and propping their feet on the rail. Saved again.

And again, in 1972, when the summer cabin leases were extended another 20 years. But if there was a reason, it seems either no one remembers or no one’s talking. The lease for my family’s cabin, Creekmore cabin (#6), was signed by my older brother Richard Somers Creekmore, Jr., making his mark. He was just five years old; and my twin sister and I were babies. (Good looking out, bro.)

As the leases approached their expiration in 1992, the summer families held their mist-ribboned breath as they had 20 years earlier and 20 years before that. But this time, no extension came. Losing our Elkmont, so long in dying, felt more like a sudden death.

The original plan for the use of the land was to let it go back to nature—a practice some referred to as benign neglect.

The cabins would not be maintained; they’d be razed, moved, or allowed to decay on their own, wiping out the summer community who had returned faithfully for a century or so. There had to be another way.

And there was.

In January 1993, My aunt, Eleanor Creekmore Dickinson, submitted an Application for Designation as an Historic District for Elkmont to the Tennessee Historical Commission in Nashville. Turns out there was something worse than losing our Elkmont. It was Elkmont vaporizing.

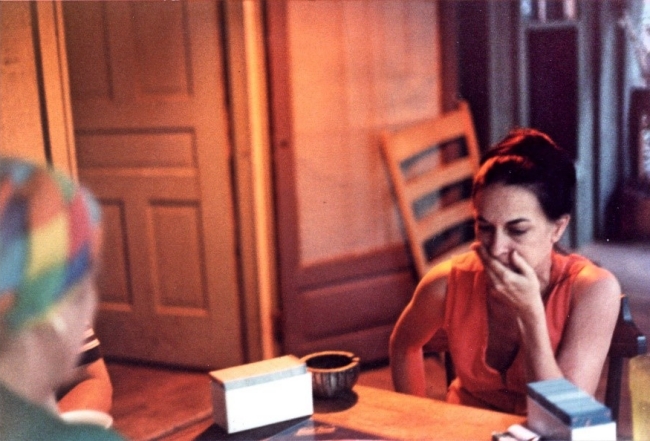

The original fun aunt, Aunt Eleanor was one of the Elkmont greats. She was a renowned artist who loved to shock people, and the subject of her life was drawing people at religious revivals in the hollers around Elkmont.

After some harsh words and uneasy compromises from every quarter of the human Elkmont ecosystem, reason prevailed. What the wildlife must have thought of us. A portion of the Elkmont summer cabins was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in March 1994.

Learning which cabins would be spared and which would not was like a reverse Christmas. To be preserved, a cabin had to meet certain standards of historical significance and structural condition. I’m grateful my family’s cabin made the cut, when so many did not. I can still picture them where they should be.

Unfurnished now, the remaining cabins are open to the public to walk through during the day. The Appalachian Clubhouse and The Spence Cabin (#42) can also be reserved for daytime events—like Elkmont reunions. As our parents and grandparents did, we still gather in Elkmont to sing “Elkmont Will Shine Tonight.”

Although Aunt Eleanor led the charge to save Elkmont, she didn’t consider the victory, as many of us did, an extraordinary feat pulled off by one of our best. She considered pursuing preservation the right of any ordinary U.S. citizen who loves a place like a person and so desperately wants a little longer.

Evelyn Creekmore spent 21 summers at her family cabin in Elkmont, Tennessee in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. A content strategist and copywriter by day, she is currently working with her cousins, Katy Dickinson and Peter Somers Dickinson, to reimagine the memoir of their mother (and the author’s aunt) Eleanor Creekmore Dickinson, The Art of Saving Elkmont. It’s currently in submission and was a finalist for the 2023 Great Smoky Mountains Association Steve Kemp Writer’s Residency. Evelyn holds an MA in writing and rhetoric from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

**Featured image is from a plaque located at Elkmont’s Appalachian Clubhouse, photog. Delonda Anderson.

I always heard about Elkmont but now I know the history. Thanks! Great story.

Thanks so much, Susan! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

I was pleased to have the opportunity to meet you and gain more insight, from one that was witness to the events.

Doug

Thanks for all your support of all things (and people) Elkmont!