For a half century Wendell Berry has been on record defending small communities and local economies, dating back to his 1977 treatise The Unsettling of America, which, as Appalachian author Wilma Dykeman once observed, deserved to unsettle America more than it did. In his roles as poet, essayist, novelist, and, most especially, small farmer, Berry has challenged the thinking and practices of corporations willing to devalue human beings in favor of profits and “labor-saving” technologies.

As a Kentuckian, he has been critical of the coalmining industry, whose absentee landlords refuse responsibility for the catastrophic messes they leave behind for the land and its people. He also takes issue with agribusiness and its mission to eradicate small farms while obscuring the connection between an individual’s food and its production.

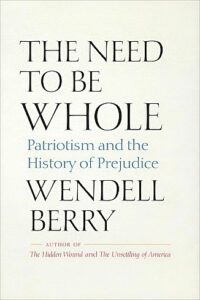

In the author’s 2022 book The Need to Be Whole, Berry returns to these considerations, emphasizing, as before, a studied and careful stewardship of land if society is to survive. Berry’s overarching theme presupposes the essential nature of neighborliness, inviting us to ask what it means to be a good neighbor and how do we live among our fellow creatures in ways that are honorable, just, and sustaining. He encourages us to consider the totality of our relationships, recognizing that “animals are our neighbors in the ecosphere.”

Berry has set himself the gargantuan task of tracing the effects of our nation’s twin themes of violence and exploitation, resulting in a concatenation of problems all connected. In short, Berry offers a kind of unified field theory of our ills:

The willingness to exploit people is never distinguishable from the willingness to destroy the land. Moreover, our race problem is intertangled with our land and land use problem, our farm and forest problem, our water and waterways problem, our food problem, our air problem, our health problem.

Berry discounts the magical thinking that capitalism can solve problems that capitalism created. The exploiters, characterized by the pioneer, the tycoon, the coal operator, and the carpet bagger, stay in one place long enough to erode its human and natural resources. The damage they do is not easily undone. In stark opposition to the plunderer is the nurturer who “stays put,” finding satisfaction in localized ways of thinking and being. The person typifying this agrarian life rooted in the earth is the small subsistence farmer who rejects the notion that “moving up means moving out.”

Slavery, the author acknowledges, was the most salient form of contempt for the land and the people forced to bring forth its fruits for profit they had no part in sharing:

The white man, preoccupied with abstractions of the exploitation and ownership of the land, necessarily has lived on the country as a destructive force, an ecological catastrophe, because he assigned the hand labor, and in that the possibility of intimate knowledge of the land, to a people he considered racially inferior; in thus debasing labor, he destroyed the possibility of a meaningful contact with the earth.

The staggering weight of white men’s offences would inevitably result in despair—what philosopher Søren Kierkegaard called “a sickness unto death”—if not for the radical love that lies at the heart of Berry’s hopes for reconnection and healing. The author acknowledges his debt to fellow Kentuckian and Affrilachian poet bell hooks for shaping his thinking over several decades of conversation between the writers. In hooks’ words, “The true work of love is to repair what the artificial boundaries of race, class, and gender [that have] split us apart.” This love implores us to love our (political) enemies and be willing to forgive and be forgiven.

I rarely take issue with the gist of Berry’s meditations, and I’m not sure I am now. However, I’m struck by Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s admonition to avoid “cheap forgiveness.” Bonhoeffer was a German pastor, theologian, and anti-Nazi dissident implicated in a conspiracy to assassinate Adolph Hitler. He was captured, placed in a concentration camp, and executed by hanging on August 9, 1945. Because he embraced radical love outlined in the Gospels, he knew his decision to participate in the assassination coup repudiated everything he believed. Bonhoeffer’s existential anguish was heightened to the point he could offer only one summation:

The ultimate question for a responsible man to ask is not how he is to extricate himself heroically from the affair, but how the coming generation shall continue to live.

I can only assume Bonhoeffer knew his convictions required him to extend love and forgiveness to his captors even as they and their superiors engineered the murders of millions. Jesus may have said “turn the other cheek,” but he drove the money lenders from the temple.

In a turn of thought I never expected, Berry advocates radical forgiveness for a morally disenfranchised segment of population in nineteenth century America: Confederate soldiers and their families. The author argues that the Civil War is almost never regarded with the complexity it deserves. He has a special animus toward those agitating to tear down Confederate monuments. To Berry, these actions represent a shameless form of censorship fueled by hatred of those long dead:

To the best of memory, the most perfected of the public angers or hatreds in this country since our hatred of the Japanese during World War II is the present politically correct or leftist hatred of the Confederacy and the Confederate soldiers. This is a moral hatred, complete to the extent of incorporating the modern day principle of no forgiveness. And it is a hatred uncomplicated by fear, because these hated enemies are all dead. And so this is a hatred of unusual purity, hatred true and whole and nothing else, and it has a familiar eagerness to search out and punish dissenters and sympathizers. It is in fact a harder, purer, more vindictive hatred by far than most of the veterans of the two sides displayed at the end of the Civil War.

Berry seethes at the faux indignation of progressives who would limit the parameters of historical discussion. How, he asks, are they any different from the book burners and anti-critical race advocates in places like Florida? However, Berry’s argument with the monument deniers evades some important considerations.

The first is that most Confederate monuments were erected in the early twentieth century in the era of Jim Crow when Klan membership was on the rise. I have heard people wistfully declare that the Confederate flag is a symbol of heritage and not hate. Unfortunately, that is an old canard (despite being catchy) masking as fact. My answer to the flag wavers is that if the flag represents heritage, then we Southerners shouldn’t have let Kluxers, skinheads, and white supremists coopt it for their own purposes which are expressly violent and racist. It takes little imagination to conclude that words and symbols can signify clear and present dangers in a democracy.

Another problematic concern is the author’s insistence on a dichotomy between agrarianism and industrialism, treating them as mutually exclusive means of production. While he gets no argument from me when saying that one enduring effect of industrialism was to make slaves of us all, Berry conveniently ignores the symbiotic arrangement fueling the economies in both regions of the country. In its simplest formulation, the North needed cotton; the South needed capital. If we can accept that this economic reality was the state of things in mid-nineteenth century America, then we can safely say that the North had blood on its hands as well.

This review has proven a labor of love for me. I recall Henry James’ description of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick as a “big, baggy monster.” Berry’s sprawling book fairly qualifies as such. The digressions, which the author obviously considers necessary, were tedious and disruptive for this reader. Berry has covered much of this ground in earlier books less shrill and more nuanced in their analyses. The writer’s connections are tenuous at times, too. Maybe a book of this scope is bound to display lapses. In no way should these detract from the totality of work by a writer who’s proven to be morally magnetic North for half a century. While readers may take issue with some of Berry’s conclusions, it may be in our best interest to suspend judgment momentarily, taking time to recall some lines by Berry’s friend and colleague, poet Robert Penn Warren:

So let us bend ear to them in this hour of lateness,

And what they are trying to say, try to understand,

And try to forgive them their defects, even their greatness,

For we are their children in the light of humanness, and under the

shadow of God’s closing hand.

**Featured image: Sean Foster, Unsplash

Excellent review. I especially appreciated your historically-informed corrective on the subject of Confederate monuments (and am disappointed that Berry abandoned himself to superficiality on the matter). Also, on the “agrarian” issue, you and your fellows at appalachiabare would enjoy (if you haven’t already seen it) this particular article on the post-Brown desegregation of the Clinton, TN, schools; it has a piquant ingredient relating to the literary, capital-A Agrarians: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/08/07/the-civil-rights-showdown-nobody-remembers