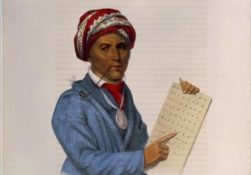

He was a pariah among his own people, having been born with a club foot. His formal education ended early because boys at school taunted him. Maybe that was fate’s way of ensuring the child, who later became Sequoyah, aka Edward Guess, inventor of the Cherokee syllabary, discovered in his limitations the extraordinary ability to accomplish a singular feat like none achieved before or since. To our knowledge, Sequoyah enjoys the distinction of being the only person in history to create a rule-governed language, one that enabled the Cherokee to enter more fully into the society of their white neighbors. In 1825 the Cherokee nation officially adopted the writing system developed by Sequoyah. Soon the literary rate of Cherokee people surpassed that of surrounding European-American settlers.

Ironically, the Native American polymath never learned to read or write in English. Yet, he was aware of the stigma attached to a people possessing no written system for the transmission of culture. As early as the 1600s in Europe, debates sparked about whether non-white, indigenous societies were capable of developing higher order cognitive skills such as reading and writing. The overwhelming consensus held that they were not. The tragic consequences of this Eurocentric bias were the slaughter and enslavement of entire cultures deemed inferior or sub-human. Sequoyah’s syllabary went far in challenging toxic assumptions about the alleged “soullessness” of America’s tribal populations.

As with all languages, Sequoyah’s syllabary is a code. Its potential messages are encrypted in a system of 86 characters resembling Roman, Cyrillic, and Greek letters and Arabic numerals. The syllabary is different from an alphabet. Typically, each letter of the alphabet is a syllable representing a sound. In Sequoyah’s syllabary, each character represents a syllable in the language. According to language scholars, no apparent link exists between sounds in Cherokee and those in other languages.

At first, the new invention received mixed reviews. Even a majority of Cherokees were skeptical, some friends and neighbors believing that Sequoyah’s syllabary was the result of sorcery. His wife is said to have burned an initial work, deeming it witchcraft. Sequoyah first taught the syllabary to his six-year-old daughter, Ayokeh, because he could not find an adult willing to learn it. When Cherokee leaders watched the girl reading from Cherokee script, they were amazed, recognizing at once the utility and potential of such an instrument. In 1824, the General Council of the Cherokees, awarded a minted silver medal in honor of Sequoyah with the inscription: Presented to George Guess for his ingenuity in the invention of the Cherokee alphabet.

Sequoyah travelled widely in his later years. In 1842 he went out West in an effort to discover remnants of the splintered Cherokee nation. This trek took him to Mexico where he taught Mexicans his native language. Sometime between 1843 and 1845, he died in the Mexican village of Zaragoza.

Sequoyah’s syllabary influenced the development of other indigenous writing systems in the U.S. and Canada. The syllabary was also used by the United States armed forces in World Wars I and II for coded radio and telephone transmissions. Native American “code talkers,” people employed to send messages, used words from the Cherokee language for each letter of the English alphabet.

Sequoyah’s legacy lives on in other, numerous ways, including the following:

- Statue of Sequoyah in Oklahoma’s National Statuary Hall Collection (1917)

- United States Postal Service issued a 19-cent stamp in his honor in the Great American Series (1980).

- Sequoyah Birthplace Museum in Vonore, Tennessee

- Johnny Cash sang about Sequoyah in his song, “Talking Leaves.” (1964)

- The Sequoyah trees in California were named for Sequoyah. (1847)