**Photo Source: Library of Congress

The history of the Southern Appalachian region is a saga of exploitation by profiteers inimical to the aims of ordinary people to provide for their families in safe conditions. The brutal treatment of coal miners and their families is well known and thoroughly documented. However, coal wasn’t the only commodity valued by absentee landlords. Copperhill, Tennessee, located in the southeast corner of the state, derived its name from the copper deposits discovered there in 1843. A website for the Carolina Ocoee River Tours describes what happened next:

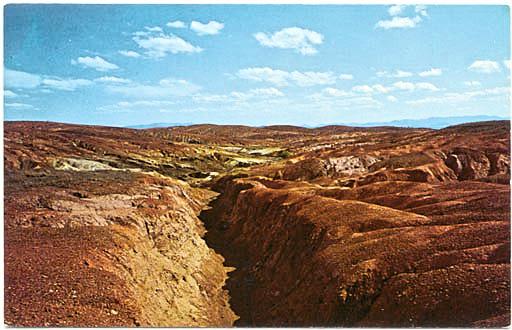

After the discovery of copper ore the rush was on. More than 30 mining operations would spring up over the next few years. The mining companies used smelting to separate the copper from the rocks and cut timber to fuel the smelters. The resulting sulphuric acid (acid rain) and deforestation devastated the environment. The copper basin became a barren man made dessert of red clay that covered thousands of acres.

As a boy growing up in the 1960s, I witnessed first-hand the wasteland that was Copperhill. Knowing my passion for collecting rocks and minerals, my dad planned an all-day outing for us in the copper basin region of Polk County. He promised that we’d scour the area near the abandoned mines where we’d likely find hematite, obsidian, and pyrite, or “fool’s gold.” Daddy explained that copper wasn’t the only ore mined in the basin. The copper, too, contained significant Sulphur content, a fact that would ultimately spell disaster for the inhabitants and landscape of Copperhill and the surrounding environs.

I especially wanted to locate a specimen of fool’s gold, so called because of its superficial resemblance to gold. Like a crow, I was hypnotized by all things shiny, and I’d read that the name pyrite derived from a Greek term meaning “of fire.” Daddy explained that pyrite was often found in coal beds.

As we traveled on Highway 68, my father tried to prepare me for what we were about to see, explaining that mining practices over the decades had ravaged the landscape. In particular, the Polk County ores co-mingled with Sulphur. When the smelting process occurred, sulphur dioxide was formed which later rained down as sulphfuric acid, i.e., acid rain. As a result, 50 square miles was stripped of vegetation, resulting in soil erosion and huge gullies making it impossible for plants or animals to survive.

Not even Daddy’s stark description, however, could prepare me for what awaited. As our car crested a final hill, the full panorama of devastation engulfed us, spilling into the windshield with inescapable impact.

“They’ve tried reforestation programs for years,” Daddy said, “though none have worked.”

Suddenly I recalled where I’d witnessed this scene. It wasn’t in real life but in pictures of an encyclopedia purporting to show the surface of the moon complete with gully-sized craters. As a ten-year-old, I felt fortunate to have survived the threat posed by the Cuban Missile Crisis a year before. Now I wondered whether this was what my neighborhood would have looked like in the wake of an atomic fireball. I concluded that an A-bomb couldn’t do much more damage than the mines had done.

As we snaked our way down into the basin, I spotted two bulldozers chewing up a bank of red clay. I asked Daddy what they were doing since their efforts appeared fruitless.

“They’re with the CCC – the Civilian Conservation Corps. They’re trying to remove copper and sulphur leached soils.”

“Will they succeed?” I asked.

“Remains to be seen. Not anytime soon, I suspect.”

I figured if anyone knew, Daddy did. Although an engineer by education and training, my father had a passion for history, in particular that of the southern Appalachian region. As we gathered rocks at the mouth of an abandoned copper mine, dropping the specimens into a draw-string potato sack, Daddy shared a stunning fact that left a lasting impression on me.

“At one time, the mine operators hired boys as young as eight to separate copper ore from coal deposits. They were called breaker boys because they broke the rocks with their bare hands.”

I paused, staring into the mine’s opening that in my imagination transformed into a dark gaping mouth swallowing all light in its vicinity.

“Weren’t the boys afraid, Daddy?”

“They were probably too young to know to be afraid.”

In that instant, I knew what hell was: a mine belching thunder and raining down poison until there wasn’t a sprig of grass left anywhere. I was glad when Daddy called it a day and we headed home.

That was my first and only time in Copperhill. Something about the experience scarred me. Maybe it was the unrelenting ugliness and desolation for miles. Maybe it was the horror at learning how children were abused and exploited by the mining industry and how, but for the grace of God (if that was indeed what it was!), I could have been a breaker boy crawling into cramped spaces and breathing poisonous fumes.

The mines are closed now. In the several decades since my visit, vegetation has returned, and the water quality of surrounding creeks and waterways approaches pristine conditions according to a study published by the EPA. These ongoing reclamation efforts are the work of various environmental conservation groups. Although it’s true that almost half of Copperhill’s 400 residents live below the poverty line, the town is enjoying a burgeoning reputation as a tourist hub for hiking, mountain biking, and white-water rafting. The best news may be what the future holds for Copperhill’s children whose school received a grant for teaching students how to develop and sustain a healthy ecosystem. One hopes they’ll also view their region as a stark example of devastating environmental damage resulting from hazardous practices and unregulated industrial development. With the efforts of this generation of young people, we may witness a cleaner and greener Copperhill – a place they’ll be proud to call home. They have an opportunity to create a legacy. We have a responsibility to encourage them.

I like the way you wove your personal experience at the mine into the historical narrative. The comparisons of the Copper Hill devastation to the moonscape and atomic bomb destruction triggered the emotions of the place and the era. You captured the “shock and awe” that those denuded and eroded red acres evoked in its witnesses. Around 1968, I worked at Camp Cherokee on Parksville Lake (aka Lake Ocoee) in Polk County. The water had an odd smell and a greenish tint that I assumed were vestiges of the upstream Copper Hill works. In the early 70’s, I took some photos of the Polk County moonscape for a class at UT Chattanooga. Now, as I drive from Asheville to Chattanooga through Polk County, I marvel at how much has changed, yet wonder what poisons, if any, might still lurk beneath the surface. Your piece has inspired me to visit the Ducktown Basin Museum at the old Burra Burra Mine on my next trip to find out.

Jimmy: If you visit Ducktown Basin Museum and the Burra Burra Mine, Delonda and I would love for you to record your adventure in a pictorial essay for appalachiabare.com. By editorial essay, I mean both pictures and prose. We hope you’ll consider doing that for us.We value your work tremendously! Best, Eddie

Eddie – it will probably be some months (e.g around Christmas) before my next trip that way. If I make it to the museum, I’d be glad to give a photo essay a shot.

Note: Admin has responded directly with info.

I am attempting to locate the appropriate person to contact regarding a faded, small “snapshot”, an aerial view of the Copper Hill, Tennessee CCC camp. On the back are the words: “3 C Camp at Copper Hill, Tn Circa 1934”. It is not a copy, but an original image. (My great-uncle was in the newspaper business in Memphis around that time, and I assume that this is how my parents came to possess this photo.) There is no “charge” for the photo! I want this image to be in the correct hands as a piece of history at Copper Creek. —12-25-2020. (I live in Jackson, Tennessee.)

And some folks say man’s effect on the environment is miniscule. Imagine that.

I’m not sure if I commented previously, but after reading this article I wanted to leave a comment. I was born in 1961 at the Copper-basin hospital. Our family lived near Hiwassee Dam in North Carolina and my dad worked in the Copper mines for about 10 years during my childhood. We often went into Copperhill and Ducktown for shopping, banking, haircuts etc. As a child I remember the distinct smell and taste in my mouth as we rode into Copperhill. I’ve been working on a memoir and my first chapter is entitled; “Copperhill, Tennessee”. I enjoyed your article and now that I am older, I have enjoyed learning more about the history of the region in which I grew up. As a child, it was just the way things were. Thank you for sharing some of your story.

Just ran across this article, after my Dad informed me that my Grandfather had relatives in Copper Hill. My Grandfathers name was Harley Dalton Haney. He lived in Altus Arkansas, which is between Coal Hill and Ozark. He died in 1980 from cancer at the age of 59 and is buried in Houston Cemetery in Altus along with my Grandmother Helen Banks Haney who died in 2000.

My name is Tim Haney and I’m interested to know if that name rings a bell with anyone living or otherwise in Copper Hill.