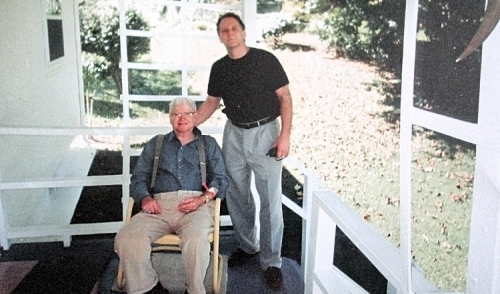

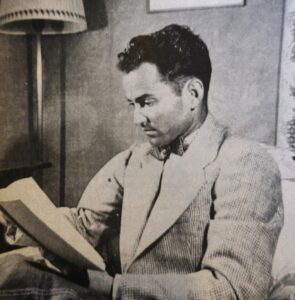

Appalachian poet and novelist George Scarbrough was born on October 20, 1915. Appalachia Bare is celebrating his birthday this week with a two-part essay written by our own Edward Francisco, titled “Christ-Hauntedness in George Scarbrough’s Invitation to Kim.” The essay first appeared in The Iron Mountain Review’s George Scarbrough Issue (Vol. XVI, 2000).

Francisco offers a unique perspective of the poet. Not only were Scarbrough and he mutual literary scholars (and masters of their respective crafts), they were also personal friends for over 30 years, until Scarbrough’s death in 2008.

“Christ-Hauntedness in George Scarbrough’s Invitation to Kim”

In the afterglow of Freud’s cultural ascendancy and the subsequent liberation of society from oppressive Christian traditions, author Flannery O’Connor surveyed the spiritual landscape only to discover remnants of a forgotten tribe. She described these hobbling wayfarers as “Christ-haunted,” a term especially applicable to Southerners who for some reason had not completely severed ties with old-time religion despite the countervailing tendencies of modernity. O’Connor saw this situation as advantageous for two reasons, both concerning the ability of art to expose concrete realities and to illuminate ultimate mysteries. No mere dogmatist, especially where art was concerned, O’Connor knew that being Christ-haunted was anything but a handicap for a writer. To approach a subject through an oblique lens was to view it somehow differently, in ways that awakened possibilities thought to be long dead and safely buried. What O’Connor was doing was rescuing Christianity from semiotic obscurity. As she often posited, the problem for the twentieth-century writer with Christian preoccupations is that the language of Christianity is worn out. It has been so overworked, misused, and abused as to be practically meaningless now. Hence, the need for nuance, resonance, and verbal dislocations that only a certain kind of poetry can provide.

It is a shame that the woman Robert Coles once called “the poet of the South” never wrote poetry or even valued it much. She confessed to a single-minded concern for prose narrative and an ongoing bewilderment at much modern verse being written by her contemporaries, some of whom she numbered among her closest friends. Otherwise, she would have been downright tickled, I suspect, to have found ample poetic evidence for her theory of Christ-hauntedness in the selected poetry of George Scarbrough, especially in his most recent volume, Invitation to Kim.

Let me rush to qualify the connection I am making between O’Connor and Scarbrough. In no way is Scarbrough concerned in the same way with distilling features of the Christian faith that O’Connor viewed as necessary to her art. Scarbrough is no apologist, no dogmatist, no adherent to any creed that I know of. I suspect from what I have read in interviews and from the conversations I have had with him that he rejects the divinity of Christ in favor of a more humanistic and historical assessment of the first-century itinerant preacher we now call Jesus.

Let me rush to qualify the connection I am making between O’Connor and Scarbrough. In no way is Scarbrough concerned in the same way with distilling features of the Christian faith that O’Connor viewed as necessary to her art. Scarbrough is no apologist, no dogmatist, no adherent to any creed that I know of. I suspect from what I have read in interviews and from the conversations I have had with him that he rejects the divinity of Christ in favor of a more humanistic and historical assessment of the first-century itinerant preacher we now call Jesus.

Nevertheless, the imagery of the Bible (particularly the Old Testament), the cadences of familiar hymns, and the sensibility of the psalmist inform Scarbrough’s work in countless subtle ways. Listen, for instance, to the poet’s own assessment of the ambiguous effects church music had on him as a child:

Hymns were largely what I had to listen to: hymns and ballads. “Amazing Grace” and “Barbara Allen,” both richly iambic and both in tetrameter. And both in different ways impressive to an imaginative child. And frightening. The almost stately, almost funereal movement of the hymn haunting and holding a threat in its promise. (Personal interview)

Even Scarbrough’s diction here supports his Christ-haunted status. Nor do we need to look far to discover the ways Scarbrough’s fundamentalist upbringing shaped his aesthetics, bridging the distance between music and metaphor:

I stood in church and sang hymns for the first twenty-five years of my life, gaining from them not only a sense of meter—which I had, of course, studied too in school—but metaphor as well. As I’ve said elsewhere, metaphorically I started at ground level: river and hill and tree and valley, and rock and dryness and wetness, desert and pastures beside not only still but clear and pure water. (Personal interview)

As Scarbrough is quick to remind us, the landscape of his origins did not always resemble “gardenlike places through which rivers ran.” Rather, home for the poet was the spiritually and intellectually arid geography of lower East Tennessee, the region settled by his grandfather in 1850. Here a boy’s impressions were never distinct from his experiences. Both land and season conspired to produce uncomfortable discoveries, one being the awful chasm that exists between vision and actuality. The Biblical promise of salvation was tempered, even obliterated at times, by the less than perfect inhabitants of the land, pilgrims in search of that most elusive of spiritual destinies: home.

For Scarbrough, the grim literality of this quest for a haven (heaven by similar derivation) can be seen in his disturbing poem “Tenantry.” The term itself describes the habit of families inhabiting someone else’s land for a prescribed period of time, farming and renting before moving on in search of whatever “signs / of a homecoming” could be found under such circumstances. Like Faulkner’s Sarty Snopes, Scarbrough grew up as the sun of a tenant farmer whose family was “always in transit / . . . always temporarily / in exile” (70). The operative word here is exile. To a boy who absorbed the Bible by osmosis from his surroundings, the parallels between his own family’s wanderings and the circumscribed travels of another, more ancient tribe of kinsmen must have been keen. Yet even the Old Testament Israelites were destined to arrive finally at that fulfillment of hopes—the Promised Land. No such promise of home existed for the young poet-to-be, for

. . . no matter

how far we traveled

on the edge of strangeness

in a small county,

the earth ran before us

down red clay roads

blurred with summer dust,

banked with winter mud. (70)

Indeed, the New Testament assurance that “in my Father’s house are many mansions” was belied by the hardscrabble facts of an existence common in the annals of the Southern poor. Scarbrough and his family were no exception to the generalized situation by which

. . . the county [itself]

was only a mansion

kind of dwelling

in which there were many

rooms.

We only moved from one

room to another,

getting acquainted

with the whole house. (71)

In one interview, Scarbrough tells of discovering that the chinked walls of the numerous tenant cabins he and his family occupied were often stuffed with newspapers. To pull out the papers was to risk exposure to the elements. Not to pull them out was to risk spiritual and intellectual malnourishment given the boy’s all-consuming appetite for words (Personal interview). It is an image wreathed in ironies—this house of words that Scarbrough describes. Not only does the boy glean what he needs to learn by reading the writing on the walls, but he must wrench the words from an unspoken subtext designed to assure his family minimal comforts. “To bring the house down around him” was an idiom all too accurate in describing the effects Scarbrough’s predilection for language would have on his family. Only by finding the right words would the child in exile be able to assign a name to his anguish or be prepared to test such paradoxical hypotheses as the one guaranteeing that the last shall be first. As for his final proposition, Scarbrough makes clear in “Tenantry” that he doubts the existence of a resolution to the human dilemma of wandering. There is no home save that of the abiding earth that awaits us all, the “tough clay, deep loam, / hill rocks, [and] small flowers” that are beautiful “for a little while.”

If geography defined the terms of Scarbrough’s early spiritual awareness—making him, in his own words, “a worshipper of place, a devotee of boundary and landmark” (Personal interview)—family offered both dispensations of love and a harsh reminder of the inherited disappointments we equate with the effects of the Fall. As numerous poems in Invitation to Kim attest, the poet’s relationships with family members assume almost archetypal proportions, displaying, at times, a toxic intensity and matchless power in shaping the boy’s life. The power of family also invokes for Scarbrough comparisons of a disturbingly spiritual nature:

May I remind you that mine was not an easy family; each member was a “church” unto himself—at times I thought “God” unto himself. Each of us was an untrespassable demesne. But there was love among us, nonetheless. That was the saving grace, as love always is because it must be. (Personal interview)

For the child of sensibility living in such a family, wounds tend to be deep and dynastic. Opportunities for love are few and must be expressed indirectly. Each member of the family plays a larger-than-life part in a spiritual drama that does not always end in death. First, there is the poet’s mother, assuming the role of a guardian angel and preserving in her son the quality T. S. Eliot once described as that “infinitely gentle, infinitely suffering thing” (15). At one point in Scarbrough’s poem “A Death in the Family,” she is termed “Mama, the equalizer, / who redivided the spoils” (58) among children not given to sharing. In a similar paean found in the volume’s title poem, “Invitation to Kim,” it is the woman’s “mother-minded weal,” her concern for the welfare of her family, that guarantees that “All things are signed here / With the personal graffiti / Of love” (8).

Of course, the presence of a protector assumes a need for protection. In stark juxtaposition to the aforementioned “mother-minded weal” exist “fragments of father / Made harm” (3). The astute reader of Scarborough’s work will perceive at once the psychological polarities that define a fiercely ambivalent relationship between father and son. No place is this more apparent that in the poem “Daddy, You Bastard,” an obvious allusion to the last line of Sylvia Plath’s benchmark poem and ferocious indictment of her father. In contrast to the hyperbolic display of emotion shown by Plath, Scarbrough reins in the passion, adopting an all but understated tone in cataloging remembered abuses. The initial figurative comparison paints an enduring portrait of the father as an ever-vigilant predator ready to pounce on his victim, the terrified son:

Daddy, you bastard,

when you were angry,

your black brows dived together

like two hawks swooping down

on the same prey:

poor, whimpering rabbit-boy,

luminous-eyed fool

trusting in the efficacy

of short grasses. (33)

Each subsequent stanza depends on finer strokes to complete the picture as when Scarbrough recalls that “Daddy, you bastard, / you always wore your hat / when you whipped me / as if to formalize the event.” Here larger-than-life terrors are visited upon the boy by a “God himself,” one insisting upon unreasonable sacrifices and scrupulous adherence to a dogma that is always changing. Nevertheless, it is the father-God’s hands the poet remembers most, for they “were golden, / bone-streaked cups of wrath.” Avoiding the father’s wrath becomes an all-absorbing preoccupation despite the sad fact that “With you I could never win” (34).

Brothers, too, are formidable and ghostly presences in “the house / That George built.” Often Scarbrough’s siblings seem to exist for no other reason than to taunt or tempt him with promises never kept. As before, the reader senses that Scarbrough’s “love of profligate / Word” (7) set him apart, making him an object of both derision and envy. More than once in Invitation to Kim, the poet refers to himself as a fool when it came to being a target for his family’s antics. The boy’s multi-colored, patchwork clothes not only link him, as J. W. Williamson points out in another context, with the motley of court jesters and fools (22), but also with the Biblical Joseph, whose many talents, represented by the coat of many colors, inspired the murderous wrath of his siblings.

Visit us Thursday for part 2 of Edward Francisco’s heartfelt and pointed article “Christ-Hauntedness in George Scarbrough’s Invitation to Kim.”

Sources:

- Eliot, T. S. (1962). The Waste Land and Other Poems. New Yor: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Mackin, Randy. (2011). George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet. Jefferson: McFarland & Co.

- Merton, Thomas. (1966). Raids on the Unspeakable. New York: New Directions.

- Scarbrough, George. (1989). Invitation to Kim. Memphis: Iris Press.

- Scarbrough, George. (1996). (E. Francisco, Interviewer)

- Williamson, J. W. (1995). Hillbillyland. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press.

**Featured image: Grzegorz Sękulski, Pexels

This was a very enlightening and thought-provoking essay. I’m especially intrigued with the “Christ-haunted” concept as you wield it to analyze Scarbrough’s work. More viscerally, my vision of Christ is how you envision Scarbrough’s, yet I can still see the world through the haze of my bible teacher mom’s indoctrination—Christ-haunted, indeed. I’m looking forward to part 2.