My first “spiritual” teacher arrived simultaneous to the literary discoveries. Anything but spiritual and much older, he drew me at nineteen into a long and difficult entanglement, a liaison lasting years that would, these days, set off all the #MeToo sirens. The sum of it was traumatizing, but there were moments of illumination. Once, on a road trip, he took me to a cabin in the woods owned by his best friend, a poet who had been working diligently on translations of a 12th century Sufi mystic poet, Jelaluddin Rumi. Spread out on long tables were pages of a manuscript written in another language, passages of poetry so beautiful that I spent time simply sitting and reading, unknowingly downloading another transmission that would much later take on meaning.

In the aftermath of that complicated era, my heart was utterly broken open. I didn’t know then that being shattered in love can be a threshold to a spiritual journey. All I knew for years to come was that, in my heart and mind–despite it looking like I had moved on–my own darkness had me searching out a more constant source of light. I converted to Catholicism, worked in the world, got married, raised children, did the things people do to establish a life rife with meaning-making. Years passed with nary a visitation from the unseen, but I now know that all those evenings swaying barefoot in the kitchen to bluegrass on the radio, baby on my hip, were spent with the same longing voices I’d encountered years ago.

It took moving to Tennessee to make a change. Like excavating an ancient tomb, I started investigating the lives of those writers who had once affected me so deeply. I started reading about their experiences of life and love, what they had read, what had moved them to express themselves in the ways they did–not that I wanted to be a writer myself; I simply wanted to understand life’s difficulties from a wiser perspective than my own. In all honesty, I wanted to make sense of my heart and its terrible pining over something I could not see but came in certain combinations of words and sounds.

This process was slow as there wasn’t any internet. Repeatedly, I encountered material from wisdom traditions I had never heard of, including what must have been Sufism. Starting with what was most familiar, I explored the inner aspects of what resonated with me most, Christianity and the message of Christ, including the revelations of the those practicing Lectio Divina or contemplative prayer, the Desert Fathers and Mothers, and the fringe Christian esoteric traditions of Rosicrucianism and Anthroposophy. During that time, there were people now passed, other teachers, who by example taught me how interconnected all these spiritual movements are and how strongly word, sounds, and light were woven together into the basketry of their worldviews. These movements all seemed to point to the same thing, but from different angles: an experiential knowledge of whatever God is. But I was reading about all that, not actively practicing what it meant to enter into states of consciousness where sound and word and light were one. I was frustrated. All this felt like headwork, data gathering.

Something was missing.

Intuitive counselor Bobby Drinnon once said to me in that amused way he had, “You know, your aura is entirely clear, like heat rising off the pavement in late July and melting into a dark, azure blue. You’ve been an open-minded extrovert all this time, wishing everyone would just get along, but since they don’t, that’s the cause of most of your troubles.” Talking with Bobby, I realized I needed to pause the headwork and plunge deeply into the experiential realm.

I returned to a downloaded memory from more than a decade before, the Sufi poet Rumi, beginning with an out-of-print volume of fifty-three short poems, variations on the ancient Persian poetic form called the rubai. Each poem was a jewel-like lens through which I could contemplate the contents of my mind and heart. But it was the preface by Coleman Barks that stopped me in my tracks. He writes,

One of the loveliest scientific ideas that I know of is Rudolf Steiner’s understanding of how plants are part of sonic systems, responding subtly to swallow wingbeats, pre-dawn warbling, and the flamboyant swamp choruses of the peepers. Certain sounds waken cellular functions. Minute mouthlike openings called stomata, for example, which plants use to exchange various aerosols and mists with the surrounding atmosphere, seem to be triggered by a combination of musical frequencies and harmonics. The birds are helping the plants! Recent researchers have found that Vivaldi, some Indian raga melodies, and Bach’s E-major concerto for the violin also stimulate cells to action. We intuitively hope and feel that this is true. Birdsong and Bach and the longing of the sitar should be meshing with the mysteries of seed germination and plant growth. O let the poems we say plump out the peaches!

These unifying metaphors, or facts, are certainly not foreign to Rumi’s vision of the dance.

Every forest branch moves differently

in the breeze, but as they sway,

they connect at the roots. (Birdsong, 10)

Sometime shortly after I read that, I experienced in a dream what all this means. Plagued for years by recurring nightmares about that relationship, I consulted an Anthroposophist friend in Nashville, a self-proclaimed clairvoyant, who advised me to meditate in a certain, focused way on my former lover from three particular perspectives for three successive nights and look for a message that would reveal itself on the fourth morning. For some peace of mind, I’d try anything, so I did exactly as she prescribed: the dream occurred on the fourth morning as predicted. Its meaning was simple and universal: that to heal and recover our inner lives from the past, our task is to immerse ourselves in helping each other rather than endlessly recycling the pain of our own experiences. Just as striking to me were the setting and imagery of the dream—an Egyptian temple, a person pushing another playfully on a rope swing and telling me we had to help each other, and all this happening beneath a rectangular transom window in the shape of a heart and wings streaming light into the temple chamber where we all were gathered. All of these were symbols and people I eventually encountered in person, years later, in the same, familiar, out-of-body manner as when hearing the Romantics.

Life opened up after that. I completed my education and became an educator myself. Simultaneously, I trained to become a licensed massage therapist, a profession I practiced for sixteen years before retiring from it. I raised my kids. Along the way, I met many incredible teachers, including a Sufi Sheikha who worked in the same building with me as an acupuncturist and doctor of Chinese medicine. Between clients, she and I entered into a three-year spiritual conversation, what the Sufis call a sohbet, which helped me further realize that the universal message of ancient Sufi philosophy was ground zero for all the other traditions I had studied all those years. This led to further discoveries that many of the writers I had come to revere the most–Goethe, Emerson, and Coleridge, for instance–had also studied deeply the great Sufi poets and Sufism and had been profoundly changed by the experience.

Here was a philosophy of the heart that wasn’t asking me to convert or believe in anything that I didn’t already experience as true. It also provided specific guidance in an experiential way to access states of consciousness reflecting aspects of merged sound and light. So, in 2005 I traveled to upstate New York to a meditation retreat (a place that immediately felt like home), was initiated into a Sufi order, and accepted a spiritual name (an appellation that, in this tradition, changes as one’s own tonality evolves with the work). For four years I trained in Universal Sufi ethics toward a Sahabat as-Safa (a designation of spiritual chivalry or futuwwa) and for two more as a salika in Suluk Academy, the esoteric school of my order. In subsequent years I discovered experientially that certain meditative states produce collateral photisms and auditory effects exactly like and even beyond those I experienced when younger. The rest I cannot speak of except to say that there is much more to be explored in terms of meditating upon light.

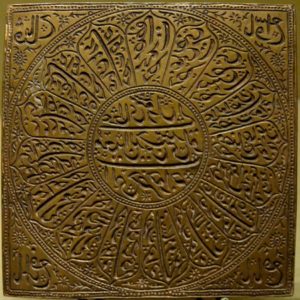

As a student, I study and practice the Chishti form of Universal Sufism within what is known as the Inayatiyya, which is not the ascetic form of Sufism associated with Islam but an inheritor of its theosophical lineage. Founded by Moinuddin Chishti (d. 1236), this order is practiced today worldwide. Its lineage exists in a chain of transmission involving four Sufi orders—the Chishti, Suhrawardi, Qadiri, and Naqshbandi–all founded by Hazrat Inayat Khan, who brought Sufism to the west from India in the early 20th century. Today, there are numerous lineages and organizations tracing their origins to him. My primary spiritual teacher is his grandson, Pir Zia Inayat Khan, known affectionately as Bawa. When I can, I attend global workshops, lectures, and discussion groups that deepen my understanding and appreciation of this path. In my everyday world, this work informs my perspective and decision-making as I teach, mentor, garden, and care for my grandkids. With a close Sufi guide and Senior Teacher, I co-facilitate Universal Sufi meditation and teaching workshops for small groups.

Sufism of any type, whether Universal or Islamic, makes an inner science of daily practices to purify one’s heart and thoughts and sublimate one’s ego or nafs so that there are fewer veils between oneself and God. Most of my teachers are Muslim, and I do most of my practices in Arabic. I am an initiate in an order (tariqa) with tremendous Persian and Indian influence that infuses traditional Sufi practices with the inner teachings of Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Universal Sufism is a philosophy or a way of being that can be incorporated into any spiritual inclination, which is why when pressed to define my beliefs, I’ll say “I’m a Christian” because I can honestly say that’s true given what I understand and value about Christ’s teachings, which are very much a part of being a Universal Sufi. It’s just that my church doesn’t look like other people’s; it’s the world. To me, it seems rather arrogant to say I’m a Sufi, so I tend not to even mention it, considering the magnitude of its history and inner teachings that I’ll never even come close to mastering.

As someone whose inner life was awakened by the power of sound and words, I find it relevant that I study the teachings of a classically trained and revered Indian musician, a master of the vina. When Inayat Khan relocated to the west from India in 1910, he relinquished his study and practice of music to focus solely on teaching Sufi philosophy because he realized people’s need for a unifying way of practicing their individual and diverse beliefs. In Inayat Khan’s many volumes of teachings, there are ten foundational principles of Universal Sufism:

1. There is One God, the Eternal, the Only Being; none exists save God.

2. There is One Messenger, the Guiding Spirit of all Souls, Who constantly leads followers towards the light.

3. There is One Holy Book, the sacred manuscript of nature, the only scripture which can enlighten the reader.

4. There is One Religion, the unswerving progress in the right direction towards the ideal, which fulfils the

life’s purpose of every soul.

5. There is One Law, the law of reciprocity, which can be observed by a selfless conscience together with a

sense of awakened justice.

6. There is One Brotherhood and Sisterhood, the human brotherhood and sisterhood, which unites the

children of earth indiscriminately in the Parenthood of God.

7. There is One Moral, the love which springs forth from self-denial, and blooms in deeds of beneficence.

8. There is One Object of Praise, the beauty which uplifts the heart of its worshippers through all aspects from

the seen to the unseen.

9. There is One Truth, the true knowledge of our being, within and without, which is the essence of all wisdom.

10. There is One Path, the annihilation of the false ego in the real, which raises the mortal to immortality, and

in which resides all perfection.

That’s more than enough for me. If this life journey is about eventually coming to peace with oneself and finding ways to give back to it with gratitude, Universal Sufism is helping me do that. One principle of Sufi ethics is, “Hold your ideal high in all circumstances,” something that reminds me regularly of how I fall short, but that’s okay (see tab 9). As Goethe implies at the end of Faust II, maybe being human is not all about sin and redemption. Maybe, after all, it’s the striving that matters.

**Featured image by Jackson David on Unsplash