Introduction

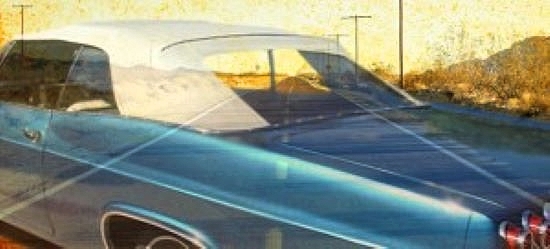

I was born and raised in Clendenin, West Virginia, a small town in Appalachia. When I was fourteen, my mom piled me and my sisters into a brand-new blue Chevrolet Impala convertible and we headed west to California, then to Miami, and finally back to West Virginia for a while. Blue Impala blossomed from my short story, “Blue Impala,” a finalist in Glimmer Train’s “Short Story Award for New Writers.”

The novel’s main character, Janie Summers, goes on the ride of her life with her eccentric and larger-than-life mother, Velvet, and sisters Mel and Sam. Janie is seeking a safe harbor—in place, time, and spirit. A wise-for-her-age and odd child from the heart of Appalachia, Janie’s coming-of-age journey to find this illusive place is fueled by a 1965 Blue Impala, in both mundane and magical ways, including Voodoo and a TV variety show called Hillbilly Heaven.

Against the backdrop of the mid-60s to mid-70s cultural revolution, Blue Impala spans a 15-year period in which Janie and her sisters live a precarious and unpredictable life based on the whims of Velvet. From their hometown of Coal Creek, West Virginia, Velvet moves the family first to Hollywood and then to Miami, where they become involved in a series of increasingly compromising events. Things get out of hand, and they return to Coal Creek, bringing along Mambo Mama Matabay, high priestess of Haitian Voodoo.

Their hope of resuming a normal life in Coal Creek is thwarted by accusations of devil worship, a return of Velvet’s stalkers, and the collapse of the Coal Creek Bridge, which kills many. These events cause Janie to re-examine her place and purpose in the world, including her fraught relationship with Velvet. Blue Impala proves that the journey to find one’s place in the world can be as illuminating as the destination itself.![]()

Blue Impala

Chapter 11

Coal Creek 1971

“Fashion Flair for the Living and Dead”

Mama decided to return with us to Coal Creek. Velvet and Mama would start a little business, Makeup and Voodoo, while they planned the launch of The Velvet Summers TV Show starring Velvet Summers, with guest appearances by Mambo Mama Matabay, High Priestess of Voodoo, and by Opal, Friend to the Stars.

But first, Velvet planned to do makeup for the recently deceased, in addition to her Fashion Flair parties held for the partially-to-fully alive, and Mama agreed that it was best not to mention the word Voodoo initially. She would say, when asked, because she certainly would be, that she practiced a form of Catholicism, which was truth enough.

For the first time since we left Coal Creek six years earlier, Velvet made a decision about our future that wasn’t solely based on what a man wanted or demanded. Although it was true that one of the reasons we were returning to Coal Creek was to escape the stalker, whom, if we didn’t agree on his identity, we at least all seemed to agree that it was a man; this time there was a plan in place, which had been fully developed and would soon be executed by women.

Velvet rented a three-bedroom house right across the street from Daddy’s trailer, which she now owned. He left it, his only tangible property, to her, and although it wasn’t much, it would serve temporarily as a business location for her and Mama. I enrolled at Charleston Community College, and Mel began classes at West Virginia University in Morgantown to pursue a master’s degree in Appalachian Studies. Sam started high school in Coal Creek.

“This time we won’t leave a forwarding address,” Velvet said. I didn’t say what I was thinking, that whoever was following her would probably know where she was anyway. But Coal Creek wasn’t Miami, and I also believed it would be harder for someone to blend into a town of two thousand, four hundred and thirty-five, minus whatever deaths and escapes had taken place since we left.

Mama packed her brightly painted red and orange Volkswagen Bus with the contents of Voodoo Botanica and still had space to spare for our belongings, which included clothing and our Zenith 1966 color TV set—we’d bought it after leaving the Pink Palace, having been so impressed by the fat ballerina. Our 1965 blue Corvair was no match for the Blue Impala, but this time my heart carried an optimism that required even less trunk space. Literally powered from the rear in both cars, we left Miami on Wednesday, January 20, 1971, and headed back to Coal Creek.

The night before we left, I overheard Velvet explaining to Opal over the phone the decision to return home.

“I know I wanted to get out of that goddamned small town, and I did, but this is a business decision,” Velvet said. “Once my show takes off, I can travel the world if I want to, and you can bet that I do.”

Opal must have said something about the wisdom of bringing Mama along because Velvet responded, “It may take some time, but once people realize her powers, they won’t dare cross her.”

I wasn’t sure how much stock could be put in that assumption. I’d seen too many people do the exact opposite of what would have been reasonable, and most of them were old enough to know better. Still, I hoped Velvet was right. My admiration for Mama continued to grow.

I rode with Mama in the Voodoo Botanica bus, as she called it. Sam and Mel rode with Velvet in the Corvair. Mama wasn’t a chatterer like many people I knew who talked for no apparent reason and whose words rattled my ears like bullets hitting tin. She was a calm and lyrical speaker; it was like listening to a peaceful melody on the radio.

“What kind of cooking do the women do in your town?” Mama said.

I had never really thought about it, but she must be wondering how different it was from her Haitian cooking.

“Mostly meat and potatoes, collard greens, corn, biscuits and gravy, that type of thing.”

“Do you think they would like Haitian food?”

“I like it, so maybe.”

“Well, we’ll soon see, won’t we?”

We rode for a long time without saying anything. Then I noticed a hint of a tear in Mama’s right eye, not a full-fledged tear that ran down her cheek, but a subtle watery glistening that caused her to blink twice.

“Are you okay, Mama?”

“Ah, yes, Janie. We spiritual travelers, you and me, connect to the places where we live, whether it’s for a long time or a short time, and it’s always hard to leave them behind.”

“I’ve always just wanted a safe place to be.”

“That place must be found within,” she said. And then, she began to talk about her life in Haiti.

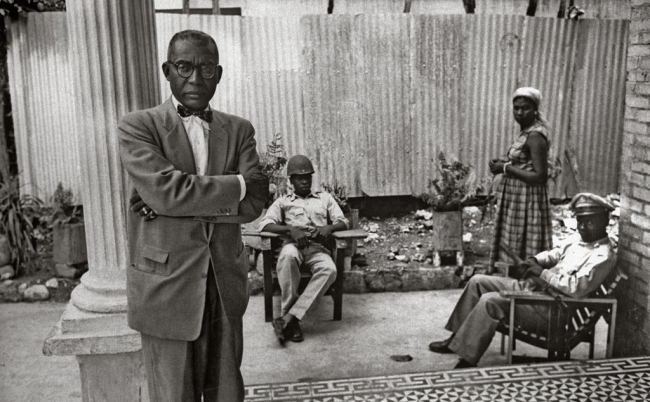

“I left in nineteen fifty-seven, shortly after Papa Doc took power,” Mama said.

“Who’s that?”

“Let’s just say he was a horrible dictator who made our people miserable.”

“What about your family?”

“My husband was put in prison for protesting. He starved to death.”

“So you came to Miami by yourself?”

“No, dear, I came with my child.”

“But . . .”

“She was a beautiful child, always smiling. But she was sickly.”

“I’m sorry.”

“She died three years ago from leukemia. She would have been your age.”

I wondered what her name was but I didn’t want to ask more questions. Mama must have read my mind. “Her name was Flore, which means ‘flowering’ in Haitian. ‘Maladi gate’ Vayan’ . . . it’s a Creole Haitian proverb that means ‘Illness spoils the most valiant.’”

At that moment, I began to understand that the heartbreak of families came in many forms, never chosen, and seldom with a desire to willingly trade for someone else’s.

Although we’d been away for only six years, you might have thought we were aliens dropped out of the sky onto the muddy banks of the Elk River. I suppose in some ways we were. For one thing, I’d stashed the Appalachian drawl under that class podium back in California, and you could be sure I had no plans to go back and retrieve it. Some kids I’d been friends with in junior high now thought I sounded like a prissy snob.

But this was small potatoes compared to the local newspaper’s coverage of our return. The most recent Mothman sighting got top billing above the front-page fold. Below the fold, a story titled ‘Summers Return,’ focused on three main “facts”—Mel was the first female to be accepted into the Appalachian Studies master’s program at WVU, Velvet was on track to become the biggest TV star since Donna Douglas, who played Elly Mae Clampett on The Beverly Hillbillies, and we had Black help.

To her credit, Velvet said that when she was interviewed for the story, they asked her about the black servant who drove the Volkswagen Bus and she told them Mama wasn’t a servant, that she was just helping. Thus, the writer referred to her as the “Black help.”

The first official Fashion Flair makeup party for the living took place in Coal Creek on Wednesday, March 3, 1971, in Daddy’s, now Velvet’s, trailer. There would have been more room had we used our rental house across the street, but Velvet said it was important to separate business from personal, plus she didn’t want it to get around town just yet that Mama was living in the house. I didn’t see much difference in “just yet” and a day or two, which would most likely be the longest it would take for the residents of Coal Creek to find out.

Velvet developed two marketing plans for her Fashion Flair business in Coal Creek, one for the living and one for the dead. For those who fell in between, the partially alive, as she referred to them, tools could be used from both.

The banner on the outside of the trailer for the first Fashion Flair makeup party for the living, read: Coal Creek’s Beauty is Everyone’s Duty, which Velvet had copied from the sign that stood on a hillside on the south side of town. Although the welcome sign on the hill referred to keeping the town clean, Velvet adopted it for her own purposes.

Before the party, Mama, Velvet and I practiced with a script. Velvet said we’d have scripts coming out of our ears when the TV show launched.

“Keeping the women of Coal Creek beautiful is every man, woman and child’s duty,” she said. “Beautiful women make for a beautiful town.”

It sounded like a bit of a stretch to me, not to mention a huge responsibility on the town’s people, but I was curious to see where Velvet would go with it.

“Women work hard, taking care of their men and children, and it’s up to all of us to ensure they look their best, in life and in death. It’s a matter of pride.”

“And how is that duty fulfilled?” I would have made a great assistant to a snake oil salesman.

“When you buy your mother, sister, wife or girlfriend a case of Fashion Flair cosmetics, you give them something that makes not only their lives better, but yours and the town’s as well.”

“How?” Mama asked.

“When you look better, you feel better. When you feel better, you are more apt to do great things.”

It was a simple approach, and we hoped to find out soon how well it worked.

The advertisement for that night’s makeup party advised the men to show up with their women from seven to seven-thirty p.m. for an introduction and demonstration. They were then free to leave, and it was expected that they all would, as there was a West Virginia Mountaineers football game that evening. Velvet had planned even this little detail, pointing out that the men would be pumped and excited pre-game and therefore in a good mood and feeling generous with their sweeties. Even if the Mountaineers lost, the men could take some comfort in the fact that they had played an important role in making their women more beautiful.

Mama, Sam and I helped Velvet set up. We bought a new couch and table for the main area of the trailer using the Green Stamps that Daddy left—fifty books worth, which Velvet pointed out was probably worth more than the trailer—and Mama donated her furniture from Voodoo Botanica, including several chairs. Ronny and Sunny Strickland were the first to arrive.

“Well, I swear, if it ain’t Velvet as pretty as ever,” Ronny said.

Sunny gave him a well-honed “don’t even start” look, and before he could say anything else, Velvet smiled and said, “And Sunny is as pretty as ever too, but I know you’re the kind of man who wants her to be as beautiful as humanly possible, which is why you’re here tonight.” I had to admit Velvet was good at this stuff.

Others arrived, twenty in all, twelve women and eight men. Velvet demonstrated the makeup application on Betty Robinson. She said she chose her because she was the only divorcee there except for Velvet, and it would influence the men in a positive way. It worked. I saw lots of men reaching into their pockets as they left.

All in all, the introduction of Fashion Flair cosmetics to the intelligentsia of Coal Creek went well. There was what seemed like at the time one small hiccup, which later may have been more accurately described as a full-fledged case of TB. Mama and I had kept a low profile throughout the evening, refilling glasses with iced tea and offering up more Ritz Crackers with Cheese Whiz.

As Mama poured her another glass, Gloria Mason said, “What do people call you?”

“My given name is Matabay, but many call me Mama.”

“You’re certainly not from around these parts. You talk different.”

“I am from Haiti.”

With that, Gloria jumped up and said she just remembered she’d left something on the stove and had to run. We later learned that’s how the rumors about Mama being from Hell started.

The day Velvet met with Mr. Blackwell at the funeral home, I went along to see Katy, my old friend. While Katy and I caught up and laughed about the Name the Cadaver game we used to play, I heard Velvet in the next room discussing her makeup business with Mr. Blackwell.

“I have my cosmetology certificate, Tom.”

“That’s all well and good Velvet, but there’s a difference between putting makeup on someone who’s alive and someone who’s dead.”

“I’ll bet there is. They don’t flinch when you accidentally stick the mascara brush in their eye.”

Mr. Blackwell laughed softly as if he might be afraid of waking the dead. “What I mean is, makeup on the living works with the heat from the body. We have to use a non-thermogenic makeup for the dead because the body is cold.”

“I’ll talk to my Fashion Flair national representative in Ohio to see what …”

“No, no, I’ll supply the makeup. If you’re interested in applying it to the dead, you’ve got a job. I don’t have time to do it all anymore.”

“Of course, I’m interested. Until I get my TV show off the ground, I could use the extra money.”

Velvet didn’t have to wait long for her first dead customer. Mr. Blackwell called the following week to say that Gloria Mason had unexpectedly passed away at the age of forty. I wondered at first if it had anything to do with whatever she had left on the stove a couple of weeks earlier that made her jump up from the Fashion Flair party to run home. But Mr. Blackwell said the cause of death was apparently a heart attack.

“Well, the poor thing,” Velvet said. “At least she was wearing Fashion Flair when she died, so she died beautiful.”

“But she’s still dead,” I said, realizing as the words came out of my mouth that Velvet would have a good response.

“Yes, and I’m going to make sure she looks as beautiful in death as she did in life.”

And from what I heard later from Katy who had attended the funeral and personally seen the dead Gloria Mason, she looked so beautiful that her husband Billy let out some sort of wild scream as he stood bent over the casket. He mumbled something to the effect of, “Her lips are so full.” Velvet admitted that she herself was in fact somewhat surprised at how large they looked, but pointed out that she had only drawn the lipstick on Gloria’s lips, that embalming was not part of her training as a cosmetologist, and if Billy or anyone else had a problem with it, they needed to take it up with Tom Blackwell.

Shortly after Gloria’s death, I ran into Sunny Strickland down at the post office. We received all our mail now at Summers, PO Box 816, Coal Creek, West Virginia, 25045. So far, there wasn’t much incoming mail since Velvet was very careful about who she gave the address to, hoping to avoid more letters from her stalker. Sunny was sitting on the little bench inside, almost like she’d been waiting for me.

“Hi Janie.”

“Hi Sunny.”

“How’s that new college you started?”

“It’s fine. I like it.”

“Terrible about Gloria, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, it sure was.”

Having covered the required niceties of salutation, personal question, and caring statement about her fellow man or woman, Sunny moved on quickly to the real point. “How well do you know that black lady who’s living with you?”

“I call her ‘Mama,’ and I know her better than I know you.”

“I don’t know about that, Janie. My family goes back a long ways in this town.”

“Why are you asking about Mama?”

“Apparently she’s a devil worshiper.”

“Where’d you hear that?”

“She told Gloria Mason the night of Velvet’s Fashion Flair party. Then a week later, Gloria’s dead.”

“I really need to get going.” I quickly checked our mailbox, pulled out a couple of envelopes, and left, with Sunny still sitting there like she was a female Columbo attempting to solve the crime of the century.

Later, I told Velvet and Mama what Sunny had said.

“Oh my,” Mama said. “The only thing I said to Mrs. Mason was that my name was ‘Matabay’ but many called me ‘Mama.’ Oh, and that I was from Haiti. I’m sorry if I’ve caused a problem.”

At that moment I heard the voice of Sister Delphi Phillips, my old Sunday School teacher, as plain as if she’d been standing right there. “Young lady, God will send you to Hades if you don’t watch yourself.” When I asked her where Hades was, she said, “It’s the same as Hell, Missy.”

“I think Mrs. Mason thought you were from Hell, because you said Haiti, which sounds like Hades.”

“I’d kill that stupid woman if she weren’t already dead,” Velvet said.

The three of us laughed so hard we had tears rolling down our cheeks, but not one speck of our Fashion Flair mascara ran, not even a little.

I have published essays in the Orlando Sentinel, a short creative nonfiction story, “Rediscovering Daddy,” in Voices of Lung Cancer, poetry in a college literary magazine, numerous articles in AAA member magazines, and reviews in Journalism Educator. I recently finished my second novel, Waiting in Place, and am now working on a compilation of my short stories and essays—Dreams of Appalachia: Take Me Home: Stories and Essays. I have a master’s degree in English Literature from C.W. Post College – Long Island University.

For more information, visit www.author-susanlong.com or email slongauthor@gmail.com.

**Featured image courtesy of Susan Long, includes the following tribute to the designer: