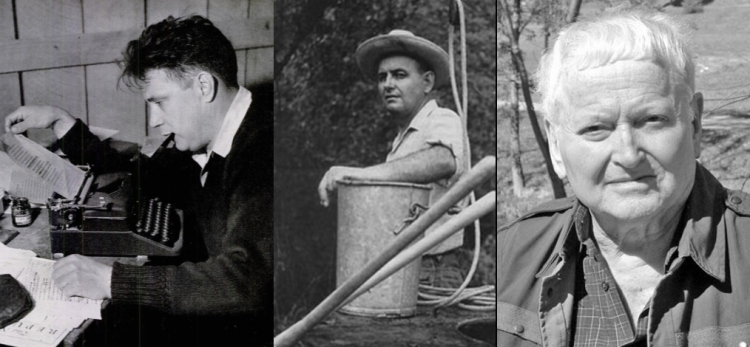

Their similarities were keen enough to define an archetype of the Appalachian writer at mid-20th century. Their differences were such as to make each a singular talent. Jesse Stuart, James Still, and George Scarbrough knew one another and admired each other’s work. All possessed shared experiences of growing up on hard-scrabble farms, all struggled to get an education, and all hailed from families they unequivocally described as “colorful.”

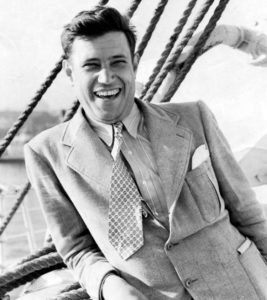

Jesse Stuart

Jesse Stuart, Kentucky Poet Laureate and chronicler of the state’s mountain life, was born on August 8, 1907, in a log cabin in W-Hollow, Kentucky. His father, Mitchell, was a farmer, coal miner, and railroad section hand. Stuart once wrote that “My father’s family was Scotch. In Kentucky the Stuarts have been feudists, boozers, country preachers, Republicans, and soldiers.” Stuart was the first in his family to graduate from high school. Afterwards, he worked for eleven months of “pure hell” in a steel mill and then enrolled at Lincoln Memorial University (LMU). After LMU, Stuart taught high school in Greenup, Kentucky. At age twenty-four, he was asked to be superintendent of Greenup County schools.

Stuart’s first book of poems, Man with a Bull-Tongue Plow, was published in 1934 and provided the impetus for his receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Stuart described how he was plowing in the field one day when he stopped and wrote the first line of a sonnet: “I am a farmer singing at the plow.” It was a propitious beginning as his first volume of verse featured 703 sonnets. His mastery of the form is seen in the following “Prayer for My Father”:

Be with him, Time, extend his stay some longer,

He fights to live more than oaks fight to grow;

Be with him, Time, and make his body stronger

And give his heart more strength to make blood flow.

He’s cheated Death for forty years and more

To walk upon the crust of earth he’s known;

Give him more years before you close the door.

Be kind to him – his better days were sown

With pick and shovel deep in dark coal mine

And laying railroad steel to earn us bread

To carry home upon his back to nine.

Be with him, Time, delay the hour of dread.

Give him the extra time you have to spare

To plod upon his little mountain farm;

He’ll love some leisure days without a care

Before Death takes him gently by the arm. .1) Francisco, Edward, Robert Vaughn, Linda Francisco, eds. (2001). The South in Perspective: An Anthology of Southern Literature. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 1110

Stuart went on to write sixty books, excelling in the genres of poetry, short stories, and novels. He died in 1984 at age 77.

James Still

James Still was no provincial writer, despite his humble origins. Born on July 16, 1906, in Lafayette, Alabama, Still lived most of his life in Hindman, Kentucky. Like Stuart and Scarbrough, he attended Lincoln Memorial University. At the beginning of his junior year, he had no money to continue college. A professor found a sponsor, who paid for Still’s education at LMU, where he received his B.A. in 1929, and also at Vanderbilt University, where he received his M.A. in 1930.

After completing his education, Still went to Knott County, Kentucky in 1932 to search for a job during the Great Depression. He settled into working as a librarian at the Hindman Settlement School where he began to write his first novel, River of Earth, published in 1940, for which he received the Southern Author’s Award. A little-known factoid about Still was the extent of his correspondence with other major American writers, including Elizabeth Maddox Roberts, Robert Penn Warren, and Robert Frost.

Perhaps his most influential correspondence was his exchange with Frost. Frost’s existentially chilling sonnet “Design,” published in 1922, was an obvious influence for Still’s sonnet “Pattern for Death,” published more than a decade after Frost’s poem. Both poems feature a spider, Frost’s “fat and white,” Still’s “clever, fastidious, and intricate.” Both spiders hint at something dark and ominous, creating in the reader a sense of fear and dread. The fundamental question posed by each lyric is whether life’s designs are benevolent, malevolent, or random. The similarities of subject and style are seen below:

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white,

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth

Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth–

Assorted characters of death and blight

Mixed ready to begin the morning right,

Like the ingredients of a witches’ broth–

A snow-drop spider, a flower like a froth,

And dead wings carried like a paper kite.

What had that flower to do with being white,

The wayside blue and innocent heal-all?

What brought the kindred spider to that height,

Then steered the white moth thither in the night?

What but design of darkness to appall?–

If design govern in a thing so small.

– Robert Frost

Pattern for Death

The spider puzzles his legs and rests his web

On aftergrass. No winds stir here to break

The quiet design, nothing protests the weaving

Of taut threads in a ladder of silk:

He is clever, he is fastidious, and intricate;

He is skilled with his cords of hate.

Who can escape through the grass: The crane-fly

Quivers its body in paralytic sleep;

The giant moths shed their golden dust

From fettered wings, and the spider speeds his lust.

Who reads the language of direction? Where may we pass

Through the immense pattern sheer as glass? .2) Francisco, Edward, Robert Vaughn, Linda Francisco, eds. (2001). The South in Perspective: An Anthology of Southern Literature. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 1135

– James Still

What’s worse than a God or gods killing us for their sport? Answer: no god at all. All is a random configuration of molecules colliding. Frost and Still viewed life through the same lens. Too, their poems display striking similarities in diction, tone, and treatment of complex metaphysical themes.

Apart from writing books, Still traveled extensively throughout his life, exploring at least twenty-six different countries in Europe and Central America. Despite his global travels, Still always returned to his log cabin in Knott County, living there until his death at age 94 in 2001.

George Scarbrough

Born in Patty, Tennessee, in 1915, George Scarbrough lamented for much of his life the lack of critical attention his work received. Certainly, Scarbrough never garnered the recognition of the poets who endorsed his books, luminaries such as Allen Tate, Andrew Lytle, and James Dickey. One reason for his omission from this elite cadre was his failure to embrace modernism and its attendant free verse experiments. Scarbrough complained about being “self taught” early in his career, and it is accurate to say that he wrote almost exclusively in traditional forms. Only with the publication of Invitation to Kim in 1989, and its subsequent nomination for the Pulitzer Prize in 1990, do we witness a stylistic transformation characterized by innovation and eclecticism. Two poems demonstrate this progression, the first a classic rhyming poem, the second an example of short-lined free verse:

Death Is a Short Word

Like a sparrow sitting in a wide walk,

I myself grew small and precise inside

In exact proportion to how much he died;

And it was thus it affected my talk.

For if he sank and wrestled in a sound,

I said immaculately thrifty words,

The beautiful, voweled speeches of birds

That love short sound,

As if in the projection of clean speech,

The bright impossible face of death

Was set backward by my careful breath,

Him I retrieved, restored. But let him reach

Pertness again, be lively, learn to smile

In some way I remembered, order died

And my amazing tongue became untied

And roar arose and lingered for a while,

Till he subsided into pale and pallid,

Closing his shining eyes: then I perceived

The catastrophic tongue again believed

Only the monosyllable finally valid.3) Francisco, Edward, Robert Vaughn, Linda Francisco, eds. (2001). The South in Perspective: An Anthology of Southern Literature. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 1122

(Polk County, Tennessee)

Always in transit

we were always temporarily

in exile,

each new place seeming

after a while

and for a while

our home.

Because no matter

how far we traveled

on the edge of strangeness

in a small county,

the earth ran before us

down red clay roads

blurred with summer dust,

banked with winter mud.

It was the measurable,

pleasurable earth

that was home.

Nobody who loved it

could ever be really alien.

Its tough clay, deep loam,

hill rocks, small flowers

were always the signs

of a homecoming.

We wound down through them

to them,

and the house we came to,

whispering with dead hollyhocks

or once in spring

sill-high in daisies,

was unimportant.

Wherever it stood,

it stood in earth,

and the earth welcomed us,

open, gateless,

one place as another.

And each place seemed

after a while

and for a while

our home:

because the county

was only a mansion

kind of dwelling

in which there were many

rooms.

We only moved from one

room to another,

getting acquainted

with the whole house.

And always the earth

was the new floor under us,

the blue pinewoods the walls

rising around us,

the windows the openings

in the blue trees

through which we glimpsed,

always farther on,

sometimes beyond the river,

the real wall of the mountain,

in whose shadow

for a little while

we assumed ourselves safe,

secure and comfortable

as happy animals

in an unvisited lair:

which is why perhaps

no house we ever lived in

stood behind a fence,

no door we ever opened

had a key.

It was beautiful like that.

For a little while.

The love of George Scarbrough’s life was his mother, Louise Anabel McDowell Scarbrough, who taught her son to read before he entered grammar school. His father, William Oscar Scarbrough, a rough-hewn tenant farmer, was a source of embarrassment to the poet, and vice versa. “He never understood my peculiar ways,” Scarbrough once wrote.

I was fortunate to know Still and Scarbrough, and Stuart, tangentially, through Scarbrough’s recollection of him. George was my friend for almost thirty years. He was a brilliant poet at his best but also a first-rate prankster. Those visiting him at his home at 100 Darwin Lane in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, will recall the rubber snakes he placed strategically around the yard and on the porch. He also never learned to drive, making him dependent on friends to take him to the grocery store and post office. “All the manuscripts I’ve sent out,” he complained, “and I’ve never so much as made my postage back.” As for being unable to drive, George dramatically recited Tennessee Williams’ Blanche Dubois: “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

I recall the afternoon George Scarbrough introduced his friend James Still to me at a literary conference we were attending. After readings and presentations, we three sat and had a fine long discussion about poets, Appalachia, and the world beyond. At one point I realized I was sitting amid Titans whose genius we wouldn’t likely encounter again. George ensured my connection with Stuart by giving me a pair of cuff links Stuart had given him: silver dolphins with studded rubies. “You’re the only person I know who’ll wear them,” he said. After Scarbrough’s death in 2008 at age 93, I learned that Pellissippi State Dean Mike North’s mother was Jesse Stuart’s niece. We had a proper ceremony at the college, during which I returned the cuff links to the Stuart family. Our marketing people didn’t want to cover the event, saying that no one knew who Jesse Stuart was.

That’s one reason I’m writing this piece – so that a triptych of Appalachian talent doesn’t die a second, more final, time. Fortunately, these sons of the region haunt me from time to time, leaving small hints of their presence. Recently, while helping my son Gabriel move into a new home in Charleston, South Carolina, I discovered a copy of George Scarbrough’s only novel, A Summer Ago. A copy can be found in the rare book room of the East Tennessee Historical Society in Knoxville.

Rarer for me was the inscription written on the inside cover:

Gabriel:

This book is for

you – a gift from

one boy to another.

Keep it in remembrance.

I love you, Buddy.

George Scarbrough

Christmas, 1994

*Poetry Sources:

![]()

**Featured Image: Compilation of the three authors

Jesse Stuart – Life Magazine, December, 1943

James Still – University Press of Kentucky

George Scarbrough – The Oak Ridger, December 2008

References

| ↑1 | Francisco, Edward, Robert Vaughn, Linda Francisco, eds. (2001). The South in Perspective: An Anthology of Southern Literature. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 1110 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Francisco, Edward, Robert Vaughn, Linda Francisco, eds. (2001). The South in Perspective: An Anthology of Southern Literature. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 1135 |

| ↑3 | Francisco, Edward, Robert Vaughn, Linda Francisco, eds. (2001). The South in Perspective: An Anthology of Southern Literature. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 1122 |

This was lovely. I’m embarrassed to admit I am unfamiliar with these writers, but I imagine I will explore them because of your tribute. I’m distressed that the ceremonial return of the cuff links was not covered; why do media types often feel they can only cover what has already been covered? The power of the current Narrative, I suppose.

Thank you, Trent. I was furious at Julia and gang for being so cavalier and dismissive, especially given our lip service to the arts. This piece was a labor of love. I appreciate your kind remarks.

Thank you for recognizing these three true Appalachians. I treasure what I know of Scarbroughs work and story’s of him shared by a common friend. The world was a better place with men like these three and I will be looking to read more of each of them.

Thanks for introducing me to these extraordinary writers. Your scholarship is impressive, and your personal insights accented their humanity. Appalachia Bare is certainly living up to its mission.

Jimmy, thank you so much. I’m ferociously protective of underrepresented talents subject to be forgotten. Given their zip codes, these writers played catch- up their entire lives. So glad you enjoyed!

You are incorrect to say that George never learned drive . I am the literary executor of George’s literary estate. I once asked him why he could not drive and he replied “Oh, I can drive.” Sure enough I found his driver’s license among his things after he died. The driver’s license is on display at the George Scarbrough Center for Appalachian Studies at Reinhardt University in Waleska, Georgia. Donna Caffee Little Ph.D is director of the Center .

Tell me: How did you become the literary executive of George’s estate? I never heard him speak of you. You will agree that George didn’t own a car. Won’t you?

That would be a pretty fair indication that he didn’t drive or, at least, didn’t want to. Besides, what a small bone you’ve chosen to pick. I think you would be happy that we at AB would want to showcase George and his talent. Driving? Seriously?