Archetypes are essential to a deeper understanding and appreciation of film and literature. Popularized by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung in the early 20th century, the word archetype is defined as a recurring symbol or motif found in traditional storytelling. This definition particularly refers to the recurrence of characters and plots sharing similar traits in various media. Archetypes tend to be assigned by gender. For instance, female character archetypes might include the following:

- The Amazon/The Crusader

- The Father’s Daughter/The Librarian/The Spinster

- The Nurturer/The Good Wife/The Martyr

- The Boss/The Matriarch/The Queen Bee

- The Spunky Kid/The Plucky Girl/The Girl-Next-Door

- The Seductress/The Femme Fatale

- The Mystic/The Free Spirit/The Quirky Misfit

In theory, this list represents a range of portrayals available to women in different contexts. However, this inventory omits one character type that may trump all the others: the Hillbilly. The word is charged with associations and laden with limitations for women unable to escape the singular fate of being born into a world of existential otherness. Their plight calls to mind Sartre’s No Exit or lines from James Dickey’s poem, “Snakebite”:

I am the one.

And there is no way not

to be me.

Hemmed in by poverty, subjected to abuse, and lashed by tongues whose only desire is to inflict wounds that result in psychic scarring, Appalachian women are beset with obstacles unique to women in their circumstances, as this excerpt from Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina will attest:

Let me tell you about what I have never been allowed to be. Beautiful and female. Sexed and sexual. I was born trash in a land where the people all believe themselves natural aristocrats. Ask any white Southerner. They’ll take you back two generations, say, “Yeah, we had a plantation.” The hell we did.

I have no memories that can be bent so easily. I know where I come from, and it is not that part of the world. My family has a history of death and murder, grief and denial, rage and ugliness – the women of my family most of all.

The women of my family were measured, manlike, sexless, bearers of babies, burdens, and contempt. My family? The women of my family? We are the ones in all those photos taken at mining disasters, floods, fires. We are the ones in the background with our mouths open, in print dresses or drawstring pants and collarless smocks, ugly and old and exhausted. Solid, stolid, wide-hipped baby machines. We were all wide-hipped and predestined. Wide-faced meant stupid. Wide hands marked workhorses with dull hair and tired eyes, thumbing through magazines full of women so different from us they could have been another species.

If Allison is correct, then we can conclude that film roles depicting mountain women will be fewer and more unsavory than those for female characters buffered from such dislocating and disadvantaged circumstances. Can we find a pattern in films featuring Appalachian roles for women? A chronological romp through the past several decades may supply the answer. We’ll start with the earliest (**Spoiler Alerts):

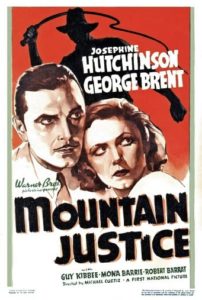

Mountain Justice (1937)

Directed by Michael Curtiz. Produced by Warner Brothers. Starring Josephine Hutchinson, George Brent, Margaret Hamilton, Mona Barrie, and Guy Kibbee.

Summary:

A Northern lawyer (George Brent) defends a mountain nurse (Josephine Hutchinson) for killing her brutal father. The film is loosely based on the story of Edith Maxwell, who was convicted in 1935 of murdering her coal miner father in Pound, Virginia.

Archetypal analysis:

Warner Brothers’ story line says it all: “A stalwart Appalachian woman finds romance as she struggles to better herself and her people amid prejudice and familial abuse.” This screenplay treatment contains all the ingredients of a hillbilly pot boiler: child marriage, mountain health clinics, and a lynching for good measure. The film isn’t subtle in making the point that mountain men are an ornery lot, especially Nurse Ruth Harkins’ father Jeff, who whales the daylights out of his daughter when she sells an acre of the family’s land to help Doc Barnard build a health clinic in the hills. A panorama of archetypes unfolds. Jeff Harkins is the quintessential “mean sumbitch.” His daughter Ruth is the crusader, caregiver, and martyr rolled into one. She is in need of deliverance; her deliverer is, not surprisingly, a man – an urbane, intelligent, and well-spoken outsider. Scratch the surface, and the outline of a fantasy materializes: the hillbilly damsel in distress is rescued by a knight driving a shiny automobile. Implausible in the extreme.

![]()

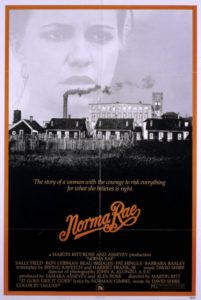

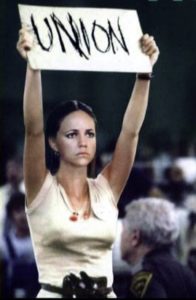

Norma Rae (1979)

Directed by Martin Ritt. Produced by Tamara Asseyev/Twentieth Century Fox. Starring Sally Field, Ron Leibman, Beau Bridges, Pat Hingle, and Barbara Baxley.

Summary:

Norma Rae Webster works in a North Carolina cotton mill that has leeched the health and livelihood of her family and friends to the point she can no longer ignore their deplorable working conditions. The film’s trailer flashes a black and white photo of Norma Rae and her two small children. A voice-over narrator announces in solemn tones that “Norma Rae has been working since she was sixteen; Norma Rae has been a mother since she was eighteen; Norma Rae has been alone since she was twenty. Norma Rae is a survivor and, for the first time in her life, she’s got a chance to become something more – a winner.”

If by winning, we mean that Norma Rae convinces her fellow workers to unionize, despite death threats and efforts at character assassination, then she indeed achieves a measure of success. But at what cost? Even with “better working conditions,” the mill women return to gritty, mindless, soul-deadening jobs. The union is their only flicker of hope.

At the film’s start, Norma is an unmarried single mother with two children by different fathers, one dead and one AWOL. A former co-worker, Sonny Webster, asks her out and shortly thereafter proposes marriage to her. She accepts because Sonny is good to her kids and doesn’t abuse her physically. Fleshing out the formula is the appearance of Reuben Warshowsky, union organizer from New York, who after a short time is smitten with Norma. At the film’s end, the two part, shaking hands, because Reuben knows she’s married and loves her husband. Reuben is the archetypal ally in Norma’s quest for justice. He also fulfills the role of the stranger who arrives on the scene and immediately upsets the status quo by acting as an agent of change. Of particular note is that Norma Rae was based on the true story of Crystal Lee Sutton, subject of the 1975 book Crystal Lee, a Woman of Inheritance by Henry P. Leifermann.

Archetypal analysis:

Norma Rae Webster fulfills the archetypal roles of nurturer, good wife, spunky kid, free spirit, and, of course, crusader. Although she has had flings with men in the past, she hardly qualifies as the seductress or femme fatale. The message is a clear one. These ultra-feminine archetypes find no place in an Appalachian mill town.

![]()

The Dollmaker (1984 – made for TV movie)

Directed by Daniel Petrie. Produced by Bill Finnegan. Starring Jane Fonda, Levon Helm, Amanda Plummer, Susan Kingsley, Ann Hearn, and Geraldine Page.

Summary:

Filmed in Cades Cove in the Great Smoky Mountains, and set at the time of the Second World War, The Dollmaker chronicles the life of Appalachian-born Gertie Nevels who is forced to uproot her children and move to Detroit where her husband plans to take a factory job. The last thing Gertie wants is to leave her Kentucky home and, for the first time, questions doing what men have always told her to do. However, her hillbilly father offers a stern admonition: “If Clovis is making a living, then you got to go to him. It’s what he wants that matters. You’re his wedded wife.” Gertie buckles under the pressure and moves, her family settling down in a tar paper shack by railroad tracks in an industrial neighborhood. Despite her new surroundings, Gertie holds onto her homespun ways, one of which is wood carving. One of the items that she cherishes is a piece of a tree limb in which she sees a figure of Jesus calling her to carve from it. Setbacks multiply almost at once: Clovis squanders money, her children behave in troubling ways, and her youngest daughter is killed by a railroad car. This last event forces Gertie to explode in rage and despair. She berates Clovis, shouting, “Don’t tell me to do it your way ever again!” Revealing that she’s been carving and selling wooden dolls to their neighbors, a strategy that Clovis has earlier mocked, Gertie declares in a paroxysm of fury: “These dolls are all that’s feedin’ our young’uns! And they’re all mine.” The only piece of lumber that she has left is the one from which she longed to carve the Christ figure. Splitting the limb with an axe, she is able to carve many dolls, ensuring that her family can return home. The Dollmaker was based on the 1954 novel of the same title by Harriette Arnow.

Archetypal analysis:

Gertie Nevels displays the grit and resilience that we’ve come to expect of Appalachian women in film and literature. She is mother, protector, martyr, dutiful drudge of a wife, and folk artist. (Note the designation of “folk”; she doesn’t qualify simply as “artist.”) Perhaps more important than what she is is what she isn’t. Circumstances beyond her control prevent her from being a crusader, librarian, free spirit, seductress/femme fatale, boss or any number of archetypal roles available to women in mainstream culture. Jane Fonda’s Emmy-winning performance as bewildered and bedraggled Gertie is light years from her role as the sizzling sexpot in Barbarella (1968). Poverty, abuse, addiction, multiple births, and lack of adequate healthcare seem staples of the Appalachian woman’s existence, whether on screen or in real life.

![]()

Winter’s Bone (2010)

Directed by Debra Granik. Produced by Anne Rosellini. Starring Jennifer Lawrence, John Hawkes, Dale Dickey (Knoxville, TN, native), Sheryl Lee, and Tate Taylor.

Summary:

In the rural Ozark Mountains of Missouri, seventeen-year-old Ree Dolly (looking much younger and frailer than her age suggests) must care for her mentally ill mother, twelve-year-old brother Sonny, and six-year-old sister Ashlee. She guarantees that her siblings can hunt and fish in preparation for lean times like the ones they are facing now. The family is destitute. Ree’s father, Jessup, has left home and not been seen for a long time. He is out on bail after an arrest for making meth. Sheriff Baskin tells Ree that if Jessup doesn’t show up for his court date, then the family will lose the house because Jessup has put it up as part of his bond. Ree embarks on a quest to find her father. She begins with her meth-addicted uncle Teardrop (in the prison system, a teardrop tattoo signifies that the wearer has committed murder). When Teardrop fails to provide information, she fans out to more distant kinfolk but meets violent resistance. For example, when Ree attempts to see the local crime boss, Trump Milton, she is severely beaten by the women in Trump’s family. When Ree approaches Milton a second time, Teardrop must rescue Ree, assuring the boss that the girl will cause no more trouble. Teardrop tells Ree that her father was killed because he was going to inform on other meth cookers. A short time later, a bondsman shows up informing Ree that she must provide proof of her father’s death in order to receive the cash portion of his bond. A few nights after, the women who beat Ree earlier come to her house, offering to take her to her “daddy’s bones.” They arrive at a shallow pond and row out to the area where her father’s submerged body lies. They sever Jessup’s hands with a chainsaw, stating that Ree can offer the hands to the sheriff as evidence of her father’s death. Ree delivers the hands to the sheriff, explaining that someone flung them onto the stoop of her house. The bondsman pays Ree the promised bond, and she and her siblings live as happily as one might expect under the circumstances.

Archetypal analysis:

There is nothing to “eulogize” in this film. Ree Dolly’s people are trash to the limit – unabashedly and unapologetically so. They would never question why they live as they do. Their trashiness is a bedrock premise of the movie. Ree is Red Riding Hood born into a family of wolves. This alchemical combination can only prove disastrous without the intervention of her Rescuer uncle Teardrop. Ree is also the archetypal Mother/Protector, Orphan Waif, and Spunky Kid. With the exception of Teardrop, the men in Winter’s Bone are devils bubbling up from a cauldron in hell. The women are crones addicted to opioids and methamphetamines, making theirs a feeble, biological pretense of life. I cannot find a spark of redemption in this narrative, leading me to wonder what is it that is so voyeuristically appealing about white trash criminal doings to mainstream audiences. The appeal of poverty porn is nothing new, of course. However, the addition of Gothic violence (e.g., lopping off hands) apparently activates the blood lust in audiences. (I’ll discuss the problematic designation of “white trash” in a future post.)

![]()

Big Stone Gap (2014)

Directed by Adriana Trigiani. Produced by Donna Gigliotti. Starring Ashley Judd, Patrick Wilson, Whoopi Goldberg, Jane Krakowski, and Chris Sarandon.

Summary:

Never underestimate Hollywood’s ability to be puckish in depicting Appalachia. The story, billed as a “drama romantic comedy,” is set in the actual Virginia town of Big Stone Gap during the 1970s. Ave Maria Mulligan, a forty-year-old independent woman, is the community’s Caregiver, home delivering medicine to the country folk, volunteering for the coal mining town’s Emergency Response Team, and directing the town’s annual production of Trail of the Lonesome Pine, based on the novel by John Fox. The plot is a hodge-podge of “happenings,” even cutting to footage of a visit to the town by Senator John Warren and his wife Elizabeth Taylor in 1978, underscoring that real-life events don’t always translate effectively into fiction. Plot complications distill down to the following in chronological order:

- Ave re-connects with Jack McChesney, a local coal miner and former schoolmate. They spend an awkward night together but part in the morning with the stiffest of goodbyes.

- Ave discovers that Sweet Sue, the shameless town vamp, has designs on Jack and plans to marry him.

- Ave’s mother dies, resulting in the discovery that her real father is alive and living in Italy.

- The ever-fickle Sweet Sue reconciles with her husband, clearing the path for Ave and Jack to find their way back into each other’s arms for good.

- The finale occurs when the townspeople lead Ave to the Outdoor Theater, surprising her with her poppa from Italy and then her momma’s sister, Maria. It turns out that Jack found them and paid for their flights, having sold his pickup truck. Jack and Ave marry.

Warning: Avoid this cinematic abortion at all costs. There’s so much wrong with this one that I don’t know where to begin. Still, I’ll try. The first point of departure from reality occurs when Ashely Judd’s Ave says in a voice-over: “When I was a girl and we drove past the coal mines it seemed like a storybook to me. Life was simple.” This paean to the heyday of coal doesn’t square with the reality that the actual Stone Gap has declined steadily in population as the demand for coal dropped, and Big Stone Gap became the first locality in America to pass a resolution in support of the federal Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. In short, actual residents aren’t wistfully sentimental about coal. Then there’s Patrick Wilson’s depiction of Jack McChesney. Has there ever been a miner so handsome, so chiseled, or so scrubbed? His coal-grimed face is obviously the creation of a Hollywood make-up artist. If you can overlook unrealistic character portrayals, then you must confront the fact that the film’s plot is a tangled skein of false starts and loose ends. My advice: If your choice is to watch this movie or clean the bathroom, I’d start scrubbing the tiles.

Archetypal analysis:

Ave Maria is a self-proclaimed spinster (though it’s hard to believe that Ashley Judd is a spinster or that she’s forty). Sweet Sue is the shameless tramp, even down to the bleached blond hair and generously exposed cleavage. Jack McChesney is alternately the “good old boy” and the “hunk.” Other characters are so negligible as to be justifiably ignored.

![]()

What to make of roles for Appalachian women in film? I canvassed more screen treatments than I write about here, but the results remain drearily the same. In eight decades, the archetypal opportunities haven’t changed much, and they’re on the losing end of desirable roles. Is that because Appalachia is an “idea” fixed in the minds of Hollywood producers and moviegoers? Or is it that the region hasn’t improved enough to alter roles appreciably? I’d say that not only has Appalachia failed to change for the better but that it’s gotten worse – especially for women. For instance, most people probably aren’t aware that maternal death rates are 60 percent higher in rural areas than in cosmopolitan locales; or that Appalachian women’s cancer mortality rate is higher in the region than in the rest of the country; or that mortality rates for diseases of despair (overdose, suicide, and liver disease) are 46 percent higher for women in the region than in the non-Appalachian United States; or, finally, that Appalachian women comprise the country’s only population demographic for whom the mortality rate is increasing at alarming percentages. The stark reality is that if you are a white, black, brown, or yellow woman in Appalachia, then you have a greater chance of dying than if you live almost anywhere else – with the possible exception of some third world countries. Statistics don’t begin to account for more staggering challenges that erode the human spirit. These latter conspire to create an obstinate legacy of shame, embarrassment, and lacerating self-loathing. An Appalachian woman once told me that the mirror was her worst enemy. Meth use and non-existent dental hygiene rot teeth. That’s why you rarely see a mountain girl smiling.

I don’t know how to solve the region’s problems. But I do know their root cause: a despair as palpable, suffocating, and inescapable as one’s skin. What we at Appalachia Bare try to provide is a venue for some of Appalachia’s best writers, artists, photographers, musicians, and folklorists as a way to showcase what’s authentic about us. Our contributors take their work and our mission seriously. We eschew cartoon buffoonery, lurid portrayals, and blatant exploitation. We want to expand the available roles for girls and women until a future time when despair is a casualty and the region’s youngest and brightest can announce proudly that they, too, have a story worth telling.

**Featured Image from UIHere

Check out the following trailers for the mentioned films (Mountain Justice trailer unavailable):

Archetypal characteristics reveal shared stereotypical traits which can shine a light on bias, assumptions, and misunderstandings.

Very nice review of women of the South, the Archetypal traits were brilliantly defined and interesting to read. Now I need to go back and watch more film. Thanks so much.