Check out the following answers for Appalachian English Quiz 3. Appalachia Bare works to provide the best available answers, with the understanding that some words are said or meant differently in various Appalachian regions. Let us know in the comments if other meanings for these words exist.

The following dictionaries were used:

- Oxford English Dictionary (OED)

- Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE)

- The Free Dictionary (This site uses several dictionaries as sources and provides links as well.)

- Meriam Webster Dictionary

- Cambridge Dictionary

Words in Middle English that might be difficult to discern are in red font. Good Luck, everyone!

1.Airish

a. hairy

b. Irish

c. breezy

d. stuck up

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), Henry Best was the first to use airish in this definition in Farming & Memorandum Books (1642): “Betwixt 8 and 9 of the clocke, and not afore, because the mornings are airish.”

Option D is technically correct, as the word is also defined as “conceited” or “snobbish” and appeared in William Hazlitt’s1)Hazlitt is considered one of the greatest English critics and essayist of all time. He had more than a handful of talents, including painting. Complete works of Michael de Montaigne in 1842.2)Montaigne (1533–1592) was a philosopher in the French Renaissance era. For our purposes here, airish was defined as “breezy” or “airy” and was written about 200 years earlier.

2. Arz

a. arts

b. arse

c. adze

d. ours

This pronunciation was an interesting one to research. The OED has a long list of English pronunciation variants, particularly in Middle English: aur, vr, vre, vur. The list continues in the 1800s: or, aar, ahr, ar, oor, ur.

The word is Germanic in origin used as “pronoun, cognate,” or “possessive adjective.” Some early forms are also arguably similar to our Appalachian pronunciation: Vár – Old Icelandic (pronounced w-ah-r) and Unsar – Gothic (pronounced oo-ns-ah-r).

3. Costez

a. coasts

b. costs

c. costumes

d. casts

The word is borrowed from French: coste, cost. Appalachians sometimes put “ez”/ “es” at the end. This addition already existed in around 1390 in MS Vernon Homilies in Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen (the oldest philological journal): “He . . . bad his hostes feede hem Þat day And sette heore costes in his lay.”

The ending also exists in the Cursor Mundi, an anonymous poem from the year 1400 with 30,000 lines: “Sir architricline, Þat . . . costes to Þe bridal fand.”

4. Davenette/Davenport

a. seaside attraction

b. horse breed

c. couch

d. tarp covering hay bales

The OED lists davenport as “a type of large, upholstered couch which may be convertible into a bed” OR “a kind of small ornamental writing-table . . . with drawers.”3)The Free Dictionary says the desk is named “after a [British] Captain Davenport, who first commissioned it. The word is North American and likely comes from a very popular and successful Massachusetts furniture company: A.H. Davenport and Company. The company began in 1880, merged with Irving and Casson in 1914, and stayed in business until 1974. They made many pieces for the White House.

The word davenette is defined by the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) as “a usually small couch.” The word is primarily from the South Midland United States.

5. Dreckly

a. outhouse

b. in a little while

c. dressy

d. carved wooden doll

The word directly first appeared in 1604 in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.4)“And who in want a hollow friend doth try, Directly seasons him his enemy.” The Appalachian pronunciation is found in 1891 in R. P. Chope’s The Dialect of Hartland, Devonshire: “I’ll kom drackly; I mus’ finish ot I’m ‘bout fust.” The OED states the pronunciation is also “dreckly.”

Another interesting pronunciation is found in Margaret Mittchell’s Gone with the Wind (1936): “terrectly.” Rhett Butler comes to visit the newly widowed Scarlett, who leans over the banister and calls, “I’ll be down terrectly, Rhett.” Sometimes the word is seen beginning with th.

6. Draw up/Drawed up

a. approach or be approached

b. sidle up to

c. when clothes shrink

d. sketch a picture

This is a tricky little phrase. The OED says it first appeared in 1175 in Lambeth Homilies: “Alswa se Þe sunne drach up Þene deu and makeð Þer of kume reines.”

Several meanings exist: having a “stiff attitude”; sewing a garment; “to pull up, stop”; bring troops in order, etc.

The DARE lists one definition, “to shrink; to shrivel up, wither,” as being from the South and South Midland United States. This usage is in Paul Fink’s Bits of Mountain Speech (1974): “My jacket drawed up ‘till purt nigh couldn’t get hit on” and “You’d better buy yore overalls long; they’ll draw up when they’re washed.” The word has also been used to describe a “charley horse” of sorts in the toes and fingers.

7. Flatter’n a Flitter

a. physically fit

b. very flat

c. what a fish does out of water

d. waste time, fritter

The OED lists flitter, as “a minute square of thin metal.” The word originates in Germany. The DARE says flitter is an alternate saying for “fritter,” which is like a flapjack. The phrase is listed in DARE as flat as a flitter and means “very flat.”

8. Give out

a. dispense

b. give up

c. tithe

d. exhausted

According to the DARE, the adjective form of the phrase give out/ given out is from the South and South Midland United States, and means “tired out, exhausted, broken down.” The phrase first appeared with this definition in 1902.

Meriam Webster gives the intransitive verb definition as “BREAK DOWN, FAIL,” and “to become exhausted: COLLAPSE.” The Cambridge Dictionary, similarly, says it means “If a machine or part of your body gives out, it stops working.”

9. High Sherff

a. seat for infants

b. tall shelf

c. sheriff

d. intoxicated state

The term “sheriff” has existed in one form or another since before the Norman Conquest, when it was scírgeréfa. “High” sheriff comes from England, Wales, and Ireland, and is used to denote a higher position than, say, a deputy. Information gathered from The Free Dictionary says the title is given to a “ceremonial officer” in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. According to the OED, the first known mention in print was in 1510 in Francis James Child’s English and Scottish Ballads under “Gest Robyn Hode” which reads “The hye sherif of Notyingham.” (The link’s spelling is “hy”)

Somewhere along the line, the term changed and was used as a “derogatory nickname.” Evidence of this exists as early as 1938, and more often after 1960.

10. Innard(s)

a. inroads

b. close kin

c. insides, organs

d. shy, withdrawn folks

This English term was originally “inwards.” The word innards appears in 1825 in Beauties of Wiltshire by John Britton (as innerds).

The DARE records “the loss of w [in the word inwards] is not attested before the 19th century . . . but appears to be widespread in English dialect.”

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines innards as “the internal organs of a human being or animal; especially: VISCERA” and “the internal parts especially of a structure or mechanism.”

11. Laig

a. large egg

b. leg

c. lake

d. lag

The word leg is early Scandinavian, from Old Icelandic leggr or leggur, Old Swedish lägge, and Old Danish leg or læg. The Appalachian pronunciation is most likely from Middle English. The e sound in Middle English can be pronounced in a few ways: ay or eh. So, leg can be “l-ay-g” or “l-eh-g.” Further, the OED documents the very spelling, laig, to be between the “pre-1700s to 1900s.”

According to the DARE, laig is “scattered, but more frequent” in the South and South Midland.

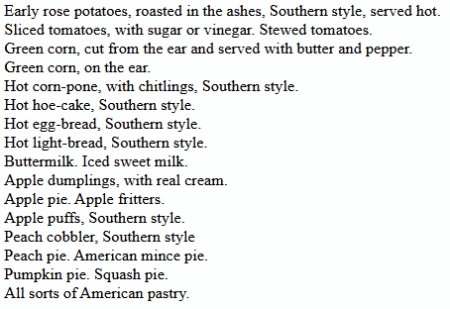

12. Light Bread

a. corn pone

b. white sandwich bread

c. angel food cake

d. slang term for methamphetamine

The OED gives one definition of light as “of bread, pastry, etc.: That has ‘risen’ properly, not ‘heavy’ or dense.” For example: a portion in William Bullein’s Dialogue Against Fever Pestilence (1564), reads “Eat light leauened breade.”

The dictionary further records special combinations using the word light, of which light bread is one. The term was first recorded on March 27, 1821 in the Western Carolinian: “Crackers and light Bread will always be found in his shop.” Mark Twain also writes about light-bread in A Tramp Abroad (1880).

One might also hear the term “loaf bread” or “flour bread” as well.

13. Nary

a. airy

b. short tale

c. none

d. narrow

The OED lists nary as a likely “alteration” of the word ne’er (never). The word is mostly used in the United States and Ireland. The first recorded usage occurs in Noah Wright’s New England Historical and Genealogical Register (1746, July): “They gave them chase, but the Indians outran and escaped them, and there was no ‘spile dunne on nary side.'”

The word is quite often used with the letter a: nary a dime, nary a one, nary a sound. The DARE states this a usage is more common.

14. Narry

a. none

b. narrow

c. DEA agent

d. narrowband communication

The word narrow is Germanic and was first recorded with a y at the end in the 1500s, with narroy. The variant narry/ narrey was used quite often in the 1900s.

The DARE records that the a in narrow was pronounced like the a in father in 1890. What’s interesting is that sometimes the pronunciation is like the a in father and other times, the sound is like the a in hat. Other forms of the word are: narrer, nar, narr, narra, norry.

15. Quile(d)

a. coiled

b. cold

c. quilted

d. quit

The word coil hasn’t been recorded before 1611, though experts acknowledge it was likely spoken as a nautical term well before then. The verb seems “identical with French cueillir” which means “to gather, collect, cull.” In Portuguese, the term colher un cabo means “to coil a cable.”

In 1611, Randle Cotgrave recorded the word in A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues: “Vrillonner une cable, to coil a cable, to wind or lay it vp round, or in a ring.” The variant quile/ quoile occurs in 1627 with John Smith’s Seaman’s Grammar and Dictionary.

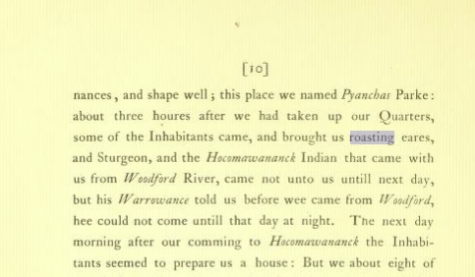

16. Roastin’ ears

a. ears of corn good to eat

b. embarrassed reaction

c. pork rinds

d. sunburned

The phrase first appeared in the mid-1600s in Edward Bland’s The Discovery of New Brittaine (1651).5)With co-authors Abraham Woode, Sackford Brewster, and Elias Pennant Though the term may have once literally meant “roasting” ears of corn, it’s widely used in Appalachia for all corn that’s ripe enough to eat.

Meriam Webster’s definition of roasting ear is: “an ear of young corn roasted or suitable for roasting usually in the husk,” and “an ear of corn suitable for boiling or steaming.” Further, Webster says the latter is located in the “chiefly Southern US and Midland US.”

17. Tetched

a. short in stature

b. taught

c. a little “off”

d. light a fuse

The word touched is English. The OED gives the adjective/noun definition as “slightly mad, crazy, or mentally unsound; a little eccentric . . . Frequently in phrases, as touched in the head, touched in the upper story, etc.” The word touched first appears in 1672 in The Authority of Magistrate About Religion6)the title is actually longer: The authority of magistrate about religion discussed in a rebuke to the preacher of a late book of Bishop Bramhalls, being a confutation of that mishapen tenent, of the magistrates authority over the conscience in the matters of religion by John Humfrey.

The pronunciation for tetched may come from tetch in the 1700s; titch around the 1700s to 1800s; tech or tich in the 1900s; or teche from pre-1700 Scotland.

18. Up’n done

a. up and down

b. went ahead and did something

c. tried but failed

d. girl’s casual hairstyle, i.e., ponytail

The Free Dictionary records “up and (do something)” as “To do something quickly, unexpectedly, or abruptly, especially without warning or explanation.” The OED says the phrase “up and” began in the 1300s in the narrative lay, Sir Orfeo: “Ac euer sche held in o cri, And wold vp and owy.” Chaucer also used the phrase in Troilus & Criseyde: “Pandare vp and gaue hym suche a cuff on the eare, that he slew hym.”

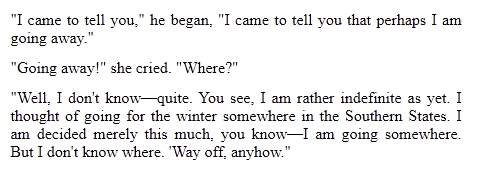

19. Way awf

a. sound a dog makes barking in the distance

b. severely troubled

d. far

e. by way of

The phrase was “formed within English, by compounding,” and was originally used in the United States. The first recorded usage was in 1836 in Slavery in America: “They are stolen from father and mother, and chained and carried way off on the ocean.”

The phrase also means “off base,” or “completely incorrect, mistaken, or misinformed,” as in – That guy’s way off on his measurements for the foundation.

20. Winder

a. rattlesnake

b. long-winded story

c. wind-up clock

d. window

The word window is originally early Scandinavian (Old Icelandic vindauga, Norwegian vindu, Old Danish windugh, etc.).

The fascinating thing about the word is the form. The Middle English form “wynt-downe may show recognition of the word’s origin as a compound” from the words “windore and wind-door.” The terms here may be the origin for our Appalachian pronunciation.

The definition for the word windore is “a window.” The first known usage dates back to 1542 in The Apophthegmes Of Erasmus, Tr. by N. Udall.

**Featured Image by Ben White on Unsplash

References

| ↑1 | Hazlitt is considered one of the greatest English critics and essayist of all time. He had more than a handful of talents, including painting. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Montaigne (1533–1592) was a philosopher in the French Renaissance era. |

| ↑3 | The Free Dictionary says the desk is named “after a [British] Captain Davenport, who first commissioned it. |

| ↑4 | “And who in want a hollow friend doth try, Directly seasons him his enemy.” |

| ↑5 | With co-authors Abraham Woode, Sackford Brewster, and Elias Pennant |

| ↑6 | the title is actually longer: The authority of magistrate about religion discussed in a rebuke to the preacher of a late book of Bishop Bramhalls, being a confutation of that mishapen tenent, of the magistrates authority over the conscience in the matters of religion |

I am plum tickled ta death ta find this here website. I was born in them mountains ye spoke of. I wuz a youngin when I lit out to find work in the northern states. Lawd, Lawd. How many times I yearned to hear the wind in the trees, the babble of the creek and the language of my people. Thank ye kindly for the trip down memory lane.

Hello Marcia. I’m so glad you liked the post! This hyeer series has certainly been enlightening and interesting. Keep us in mind for more of yore memories!