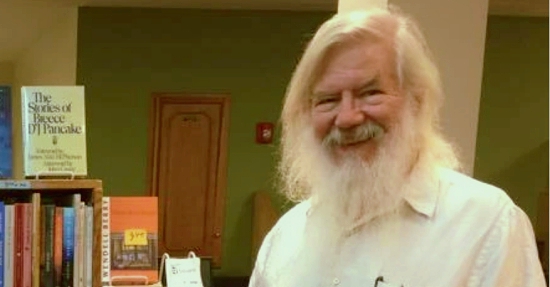

Appalachia Bare’s distinguished Associate Editor, Edward Francisco, recently conducted an interview with editor, writer, activist, and promoter of all things Appalachia, George Brosi. Our region is filled with so many people who dedicate their lives to Appalachian causes. Brosi is one such person. Please enjoy reading his bio entry and Francisco’s interview.

Biography

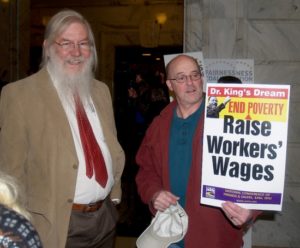

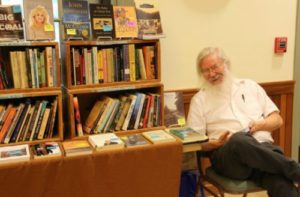

George Brosi moved with his mother and sister to join his father in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in January 1944 when the Army Corps of Engineers finished building their house. He graduated from Oak Ridge High School in 1960, Carleton College in 1965, and earned an M.A. Ed. from Western Carolina University in 1991. He is the co-editor of Jesse Stuart, The Man and His Books for the Jesse Stuart Foundation, No Lonesome Road: The Prose and Poetry of Don West for the University of Illinois Press, and Appalachian Gateway: An Anthology of Contemporary Stories and Poetry for the University of Tennessee Press. He founded Appalachian Mountain Books in 1982. It is a book business specializing exclusively in books about the Appalachian South that serves academic libraries, brings a display of books to various regional conferences and festivals, and continually updates the website, ApMtBooks.com. He has received awards for promoting Appalachian Literature from the Appalachian Studies Association, the Appalachian Writers Association, the Mountain Heritage Literary Festival, and the Hindman Settlement School. In the 1990s he taught students in humble circumstances in a prison and on off-campus centers at shopping centers on reclaimed strip mines as well as at Kentucky’s “flagship” university. In the 2000s, he edited Appalachian Heritage magazine for Berea College. In his younger days, George worked full time for Civil Rights, peace, economic justice, and environmental organizations. Subsequently he has continued to do volunteer work for progressive electoral candidates and for non-profits concerned with these issues.

George Brosi Interview

1.) Francisco – Connie Green, Marilou Awiakta, and you grew up in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Because I’ve always been fascinated with the intersectionality of writing and place, would you share some of your experiences as a boy growing up in the “Secret City?”

Brosi – I’m a big fan of both Connie Green and Marilou Awiakta, although I do not recall ever talking with either specifically about Oak Ridge. During the fifties when I was a secondary student there, I attended lectures in Oak Ridge by both Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Mead. During the question period, Margaret Mead chided Oak Ridgers for being aloof and unconcerned about the surrounding Appalachian area. And Integration happened in Oak Ridge when I was in high school. I participated in the Civil Rights Movement in Oak Ridge in the summer between my freshman and sophomore years in college, 1961. Issues of war and peace were inescapable in Oak Ridge. Civil liberties, too, was there. In high school I somehow came across a leftist magazine and innocently wrote them a letter to the editor. My father was super freaked out because he had security clearance. None of this resulted in most Oak Ridgers becoming involved in these issues, but it did for me.

2.) Francisco – Wordsworth wrote that “the child is father to the man.” Did you receive any intimations in childhood hinting that you would become an activist, editor, and author?

Brosi – I was always a rebel. I don’t know why. When it was my turn to read the Bible verse at the start of my public elementary school day, I would often read, “Jesus wept,” knowing I’d be paddled for not reading a longer verse, yet not fully understanding the irony at the time. In high school I wrote a letter to the editor protesting the fact that our basketball coach only played our African-American player when the other team agreed, but the player was conveniently declared academically ineligible before my letter could be printed. I was the only boy in Ms. Baird’s junior English class to get an A from her, perhaps she felt that her rebellious student might have promise as a writer.

Brosi – I was always a rebel. I don’t know why. When it was my turn to read the Bible verse at the start of my public elementary school day, I would often read, “Jesus wept,” knowing I’d be paddled for not reading a longer verse, yet not fully understanding the irony at the time. In high school I wrote a letter to the editor protesting the fact that our basketball coach only played our African-American player when the other team agreed, but the player was conveniently declared academically ineligible before my letter could be printed. I was the only boy in Ms. Baird’s junior English class to get an A from her, perhaps she felt that her rebellious student might have promise as a writer.

3.) Francisco – For a time, you attended college in the Deep North (i.e., Minnesota) where you were exposed to the Civil Rights Movement and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Later, you joined the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) organization and were assigned to the Ann Arbor, Michigan, office. Obviously, these experiences contributed to your increasing awareness of toxic inequalities in American society. I wonder, though. Was it necessary to travel to far-flung places in order to learn strategies of nonviolent resistance? I pose this question because you’ve indicated more than once that the arrangement wasn’t always reciprocated and that many activists from outside the region entering Appalachia in the 1960s adopted a paternalistic attitude and behaved obnoxiously.

Brosi – I’m strongly for people experiencing life beyond their own backyard. I’m thankful that I have had the good fortune of living up north and in California, but I always saw that as temporary and made a point of moving back as soon as I could. I’m also glad I have lived, for a summer or more in Appalachian North Carolina, West Virginia, and Kentucky, as well as Tennessee, in terms of my understanding of Appalachia. Sure, newcomers can be obnoxious – in fact that is the reputation that Oak Ridgers have in Northern Anderson County. The North Carolina mountains have their Florida people, and some of the young people who came to Appalachia in the ‘60s and beyond lacked sensitivity, but in every case, I think they have provided the youth, especially, with a sense that differences are not inherently threatening. Of course, it must be a two-way street of mutual respect and openness. East Tennessee certainly has its share of great writers and activists, but traveling and living different places certainly broadened my outlook.

4.) Francisco – Langston Hughes said that a writer had to be “both of the tribe and apart from the tribe.” Wendell Berry, too, speaks of his family’s estrangement from him during the years he opposed the war in Vietnam. My question to you: What was your experience being an activist – some might say radical – while living and working at home in Appalachia? You don’t seem to have been afforded the buffer of distance during one of the most tumultuous periods in recent American history.

Brosi – Yes, I am a radical. I agree with Langston Hughes, that writers almost always tend to be people who have experienced more than one culture and can get out of themselves in order to have the perspective necessary for good writing. When I was protesting the Vietnam War, I had a cousin who was career military and a cousin who worked for Dow Chemical, the makers of napalm. In 1965 my partner in Nashville was African-American, and I’ve also recently had an African-American partner here in Berea, Kentucky. So I have experienced micro and macro aggressions, both in terms of race and politics. It is a small price to pay for being able to feel like I am having at least a little impact to make life better for the most vulnerable. I am well aware that others have paid much greater prices, including the ultimate price.

5.) Francisco – When I hear the word Appalachia, Geroge Brosi springs to mind. However, I can’t think of you without thinking of your lovely wife, Connie, who was so kind and gracious to me on occasions when you visited Pellissippi State. I know you’ve said that one thing of which you’re proudest was your marriage to Connie. Share with us how you met and how your love and partnership flowered over the years.

Brosi – Connie and I met at a party after the Rally Against Repression in Nashville, a gathering in support of the Knoxville 22 who unfurled anti-Vietnam War banners at a Richard Nixon/Billy Graham event in Knoxville and were jailed. Connie had not seen me before, so she asked a friend who I was. The answer was melodramatic – “What? You mean you don’t know George Brosi? He is one of the ten most wanted revolutionaries in America.” Gross hyperbole, but it sure eased my path into her heart. Before we met she had taught at Pine Mountain Settlement School, way back in the mountains, and at an all-Black school in Nashville. Our first home was a small farm in the Sequatchie Valley. She loved kids, and we have seven of them. Our farm and garden work, our kids, and our shared commitment to Appalachia, to better race relations, and to peace was a pretty solid foundation. Her death of cancer in 2015 has been difficult for all eight of us, but it has also brought us together.

6.) Francisco – For the longest time, Appalachian writers and literature were underrepresented or, at best, considered a subset of “Southern Literature.” When you and Connie established Appalachian Mountain Books in 1982, was part of your motivation to give exposure to regional writers overlooked or ignored by mainstream publishers and critics? What else did you hope to do?

Brosi – Yes, when we first started displaying our Appalachian books, it was common for people to exclaim, “I didn’t know there were so many books about our region!” A degree of pride in one’s own heritage and self-confidence allows people to not be threatened and to feel comfortable with those from different backgrounds. Of course, there is a fine line between this kind of positive pride and the dangers of chauvinism. But books do often allow people to realize that there is bad as well as good in their own traditions and to make a point of trying to overcome the bad while embracing the good.

Brosi – Yes, when we first started displaying our Appalachian books, it was common for people to exclaim, “I didn’t know there were so many books about our region!” A degree of pride in one’s own heritage and self-confidence allows people to not be threatened and to feel comfortable with those from different backgrounds. Of course, there is a fine line between this kind of positive pride and the dangers of chauvinism. But books do often allow people to realize that there is bad as well as good in their own traditions and to make a point of trying to overcome the bad while embracing the good.

7.) Francisco – Since its establishment in 1973, Appalachian Heritage magazine has been an important venue for new and established voices in southern Appalachia. Your editorship of the magazine followed stints by Sidney Saylor Farr and Jim Gage. Obviously, you had a particular vision for AH. In which direction did you wish the magazine to go? What innovations did you adopt to achieve the goals you had in mind?

Brosi – Yes, Al Stewart and Sidney and Jim set the magazine on a strong foundation. I agreed with them – and not the current editor, sadly – that we needed to only carry the work of regional writers and to provide a mix of distinguished people of letters along with fresh new voices. I guess I was a demon for punishment because I instituted a featured author and a featured artist or photographer for each issue – again something that has been discontinued – and we invited each featured author to the Berea College campus. Like any other category of people, there are in-groups among Appalachian authors. One of my commitments as editor of Appalachian Heritage and for my current website: https://apmtbooks.com/ is to be scrupulously inclusive, both in terms of under-represented groups and all kinds of “outsiders.” For example, my website includes over 100 books about Black Appalachians. The issue of the magazine that I’m most proud of was our Cherokee issue. It has some pages with the Cherokee syllabary opposite English, and almost all the authors were enrolled members of the Eastern Band. We celebrated the issue at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, and the Principle Chief was our master of ceremonies.

8.) Francisco – Let’s hearken back to some Appalachian writers born in the early twentieth century: Jesse Stuart (about whom you wrote a book), James Still, and George Scarbrough. I’m loathe to consider the challenges these men faced in simply obtaining an education. All three attended Lincoln Memorial University and all experienced interruptions in their education because they lacked funds for sustained attendance. At times, I’m amazed they persisted. Would you discuss some of the challenges Appalachian writers have always faced given the anti-intellectual atmosphere of the region and cultural values often at odds with learning?

Brosi – There has been a strain of anti-intellectualism in society for a long time. Apparently, in the Garden of Eden, the Tree of Knowledge was viewed as the greatest threat to the patriarchy. Unfortunately, the last four years have seen a rise in anti-intellectual feeling that I hope will be short-lived. Earlier, our writers persevered through difficulties to move into an intellectual arena. Our region is blessed with what can be considered three different kinds of authors, in the past and even now: there are the well-educated ones, like Thomas Wolfe and James Agee who both went to Harvard; there are those with little formal education and an almost backwoods background like Byron Herbert Reece and Forrest Carter; and then there are those who have stepped out into a wider world, like Robert Morgan who grew up in a rural family without a car but has taught most of his professional life at Cornell, an Ivy League University. The backgrounds of regional writers – how privileged or challenged – have not been an important determinant of how brilliant or accomplished any of them have become. Impediments to receiving a good education have been reduced considerably since the 1960s due to diligent efforts by many both inside and outside educational administration, but we still have a long way to go.

Brosi – There has been a strain of anti-intellectualism in society for a long time. Apparently, in the Garden of Eden, the Tree of Knowledge was viewed as the greatest threat to the patriarchy. Unfortunately, the last four years have seen a rise in anti-intellectual feeling that I hope will be short-lived. Earlier, our writers persevered through difficulties to move into an intellectual arena. Our region is blessed with what can be considered three different kinds of authors, in the past and even now: there are the well-educated ones, like Thomas Wolfe and James Agee who both went to Harvard; there are those with little formal education and an almost backwoods background like Byron Herbert Reece and Forrest Carter; and then there are those who have stepped out into a wider world, like Robert Morgan who grew up in a rural family without a car but has taught most of his professional life at Cornell, an Ivy League University. The backgrounds of regional writers – how privileged or challenged – have not been an important determinant of how brilliant or accomplished any of them have become. Impediments to receiving a good education have been reduced considerably since the 1960s due to diligent efforts by many both inside and outside educational administration, but we still have a long way to go.

9.) Francisco – Appalachian writer David C. Hsiung notes that the word Appalachia evokes in the modern imagination a “host of images and stereotypes involving feuds, individualism, moonshine, subsistence farming, quilting bees, illiteracy, dueling banjos, and many other things.” Hsiung made that statement twenty years ago. Have we talked back enough to the stereotypes that Hsiung mentions, and, if we haven’t, how should we proceed?

Brosi – I’m a big fan of David Hsiung. I think his book, Two Worlds in the Tennessee Mountains tells an important story – I know it is a scholarly book, not a tale, but it does tell a story. His thesis is essentially that stereotypes of mountain people have mostly originated within our region, although sometimes reinforced from outside. It was and is often county seat power structures who most disdain the people who live in the hills beyond. I actually think we have talked back those stereotypes enough. Today, do women? do African-Americans? do Latinx people? do native people put lots of energy into arguing against their stereotypes? No, their energy goes into showing that they are worthy. Why call attention to the lies and thereby reinforce them?

10.) Francisco – You had to anticipate this final question. What is your assessment of J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy? Did you know Ron Howard is making a movie inspired by Vance’s memoir?

Brosi – I have had two encounters with J. D. Vance. In the first, I showed him my very negative review of his book on my i-phone. His response was most gracious. I gave him a hug the next time I saw him. The language of his book suggests that he thinks he is the only one who has overcome a challenging background. Of course, that is ridiculous. The people I know who were not offended by the book are the people who have overcome a challenging background and felt sometimes like they were the only ones, so they hardly notice Vance’s language in that regard. His language also may lead readers to think that everybody in the region has some of the negative qualities of his kinfolks, and that it is their own fault. I disagree, but I still think we need to stop writing about stereotypes. If you feel J.D. Vance’s experiences, writing or opinions do not represent you, please do not call attention to them by complaining about them. Write your own story!

Terrific interview of a man of substance.

Eddie, this was a fascinating interview on so many levels–so much richness to appreciate! First, is the delicious irony of Brosi having grown up in Oak Ridge, home of pulsed neutron accelerators and super computers, an image about as far removed as one can get from a “host of images and stereotypes involving feuds, individualism, moonshine, subsistence farming, quilting bees, illiteracy, dueling banjos, and many other things.” Second, is his all-encompassing embrace of Appalachian diversity, his intellectual honesty and his expansive knowledge of the region. The link to Appalachian Mountain Books revealed a treasure trove of books and other resources that I plan to explore further. My favorite quote, a point I have clumsily tried to make before in my comments on this blog, is this: “…but I still think we need to stop writing about stereotypes. If you feel J.D. Vance’s experiences, writing or opinions do not represent you, please do not call attention to them by complaining about them. Write your own story!” Thank you very much for introducing me to this multidimensional, unique and colorful character.

Thank you so much, Jimmy. I, too, was pleased at the way it turned out. George and I have been friends for years (he published some work of mine in the early 2000’s), and I hoped he’d trust me enough to do the interview justice. The fact is that he got burned at Berea badly by a couple of colleagues who didn’t have his, the magazine’s, or the college’s best interests at heart. I thought he deserved a venue to share his wealth of knowledge and experience about the region. I think he batted the ball out of the park! So happy you enjoyed it.

Excellent! Great interview.