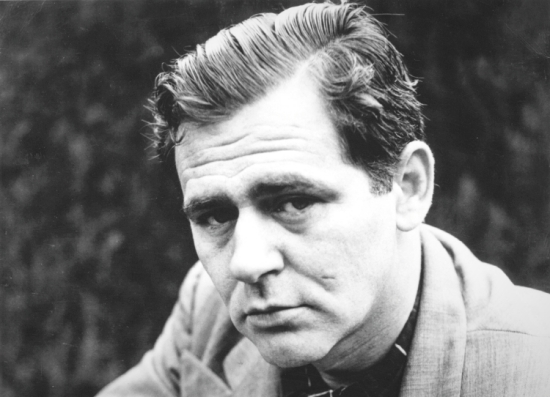

James Agee’s “Knoxville: Summer 1915” may arguably be the most beautiful prose poem in English. A prose poem is a hybrid sharing characteristics of both prose and poetry. A striking example would be the Old Testament book of Psalms found in the King James translation of the Bible. “Knoxville: Summer 1915” serves as the lyrical preface to Agee’s novel A Death in the Family, published posthumously two years after Agee’s death in 1955. The novel subsequently received the Pulitzer Prize. The book is a semi-autobiographical account mirroring events surrounding the death of Agee’s father in a car crash on the Clinton Highway outside of Knoxville. Agee was only six at the time, but his father’s untimely demise would become the benchmark event in the author’s life.

Following his father’s death, Agee’s mother moved the family to Sewanee, Tennessee, where young Agee enrolled in Saint Andrews School, originally founded to educate “barefoot boys from the Appalachian region.” He eventually left to further his education at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. Entering Harvard University in 1928, Agee became editor of the Harvard Advocate to which he contributed poetry, book reviews, and fiction. In 1934 he published Permit Me Voyage, recipient of the prestigious Yale Series of Younger Poets award.

Eventually Agee gained success as a film critic and began writing original screenplays, including Noa Noa, and adaptations such as The Blue Hotel (1948-1949), The African Queen (1950), with John Huston, and The Night of the Hunter (1954). Although Agee traveled extensively, his posthumous, award-winning novel A Death in the Family would bring him “all the way home,” the title of the dramatic version of the book made into a movie in 1962.

“Knoxville: Summer 1915” takes us back to where it began: Agee’s childhood home at 1505 Highland Avenue in Knoxville, Tennessee:

We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the time that I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child. It was a little bit mixed sort of block, fairly solidly lower middle class, with one or two juts apiece on either side of that. The houses corresponded: middle-sized gracefully fretted wood houses built in the late nineties and early nineteen hundreds, with small front and side and more spacious back yards, and trees in the yards, and porches. These were softwooded trees, poplars, tulip trees, cottonwoods. There were fences around one or two of the houses, but mainly the yards ran into each other with only now and then a low hedge that wasn’t doing very well.

Lest the reader think the preface is a paean to boyhood or to the innocence of childhood, Agee dispels that sentimental notion by acknowledging he was merely disguised as a child. The reality was fundamentally different. Agee’s memory is eidetic in recalling sights, sounds, and textures of what should have been an uneventful evening but for the impending fact of the protagonist’s father’s death. Agee’s description of the neighborhood of his youth is a unique blend of lyrical flourishes and obsessive attention to detail:

There were few good friends among the grown people, and they were not poor enough for the other sort of intimate acquaintance, but everyone nodded and spoke, and even might talk short times, trivially, and at the two extremes of the general or the particular, and ordinarily nextdoor neighbors talked quite a bit when they happened to run into each other, and never paid calls. The men were mostly small businessmen, one or two very modestly executives, one or two worked with their hands, most of them clerical, and most of them between thirty and forty-five.

Obviously, Agee offers an adult’s nuanced awareness of what he (and the book’s protagonist) registered through the eyes of a child. A child would not, for example, grasp the taboo nature of “the other sort of intimate acquaintance.” Agee reminds us that what we have read to this point is a digression, tugging us back to the subject at hand with a single utterance comprising a paragraph of its own:

But it is of these evenings, I speak.

Agee’s style is intensely literary, aspiring to the level of ancient classics, especially those in Latin exhibiting elegance, harmony, and proportionality. Because word order in Latin is fluid, in the previous sentence Agee opts to alter normal English word order (i.e., subject followed by verb followed by direct object) for rhetorical effect. The aim is to heighten the diction beyond the accepted vernacular.

Agee shows his awareness of features of classical style in the next sentences:

Supper was at six and was over by half past. There was still daylight, shining softly and with a tarnish, like the lining of a shell; and the carbon lamps lifted at the corners were on in the light, and the locusts were started, and the fire flies were out, and a few frogs were flopping in the dewy grass, by the time the fathers and the children came out. The children ran out first hell bent and yelling those names by which they were known; then the fathers sank out leisurely in crossed suspenders, their collars removed and their necks looking tall and shy. The mothers stayed back in the kitchen washing and drying, putting things away, recrossing their traceless footsteps like the lifetime journeys of bees, measuring out the dry cocoa for breakfast. When they came out they had taken off their aprons and their skirts were dampened and they sat in rockers on their porches quietly.

Obvious is that in classical, also known as Ciceronian style, the form and sound of prose are often more important than content. The beauty of language for its own sake is the aim of the writer of classical prose. Elegance is achieved by using such stylized conventions as parallelism, the use of successive and same grammatical constructions, sounds, or meter; anaphora, the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of clauses; and figuration, the use of figurative language to intensify comparisons.

In the previous passage, for instance, examples of parallel structure include the stringing together of gerunds (-ing ending words serving as nouns) in the sentence reading, “The mothers stayed back in the kitchen washing and drying, putting things away, recrossing their traceless footsteps like the lifetime journeys of bees, measuring out the dry cocoa for breakfast.” Repetition of any sort tends to be memorable and pleasing to the ear.

Agee’s use of anaphora surely owes to Agee’s knowledge of rhythms in the English Bible, especially the repeated ands, as in “. . . and the carbon lamps at the corners were on in the night, and the locusts were started, and the fireflies were out, and a few frogs were flopping in the dewy grass . . .” Agee could have eliminated the ands without any appreciable effect on the sentence. Yet, his poet’s ear grasps that anaphora lends a lilting quality to the prose, the same as can be found in many sections of the King James Bible (Genesis 1:20-23, KJV):

20And God said, Let the waters bring forth abundantly the moving creature that hath life, and fowl that may fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven.

21And God created great whales, and every living creature that moveth, which the waters brought forth abundantly, after their kind, and every winged fowl after his kind: and God saw that it was good.

22And God blessed them, saying, Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas, and let fowl multiply in the earth.

23And the evening and the morning were the fifth day.

James Agee’s favorite figure of speech is simile, a comparison introduced by the words like or as. Unlike many of his modernist contemporaries, Agee doesn’t use comparisons that are far-fetched, strained, or jolting. A simile of that sort is found in the first three lines of T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table . . .

In contrast, Agee’s similes are gentler, focusing on similarities rather than differences, and tending to reconcile opposites in the tradition of Romantic poets like John Keats. For instance, Agee creates a simile that is pleasing both to the eye and the ear when he writes, “There was still daylight, shining softly and with a tarnish, like the lining of a shell.” Agee’s most ambitious simile in the passage, however, compares the sounds a water hose makes with those of a violin: “First an insane noise of violence in the nozzle, then the still irregular sound of adjustment, then the smoothing into steadiness and a pitch as accurately to the size and style of stream as any violin.”

The paragraph in which that sentence occurs is a tour de force of sounds and the rhetorical devices creating them:

It is not of the games children play in the evening that I want to speak now, it is of a contemporaneous atmosphere that has little to do with them: that of the fathers of families, each in his space of lawn, his shirt fishlike pale in the unnatural light and his face nearly anonymous, hosing their lawns, The hoses were attached at spiggots that stood out of the brick foundations of the houses. The nozzles were variously set but usually so there was a long sweet stream of spray, the nozzle wet in the hand, the water trickling the right forearm and the peeled-back cuff, and the water whishing out a long loose and low-curved cone, and so gentle a sound. First an insane noise of violence in the nozzle, then the still irregular sound of adjustment, then the smoothing into steadiness and a pitch as accurately tuned to the size and style of stream as any violin. So many qualities of sound out of one hose: so many choral differences out of those several hoses that were in earshot. Out of any one hose, the almost dead silence of the release, and the short still arch of the separate big drops, silent as a held breath, and the only noise the flattering noise on leaves and the slapped grass at the fall of each big drop. That, and the intense hiss with the intense stream; that, and that same intensity not growing less but growing more quiet and delicate with the turn of the nozzle, up to that extreme tender whisper when the water was just a wide bell of film. Chiefly, though, the hoses were set much alike, in a compromise between distance and tenderness of spray (and quite surely a sense of art behind this compromise, and a quiet deep joy, too real to recognize itself), and the sounds therefore were pitched much alike; pointed by the snorting start of a new hose; decorated by some man playful with the nozzle; left empty, like God by the sparrow’s fall, when any single one of them desists: and all, though near alike, of various pitch; and in this unison.

The quoted portion is an extended example of onomatopoeia, a technique in which sounds mimic the senses of words. For example, the phrase “slapped grass” is onomatopoeic because the word slapped sounds like an actual slap. The short a sounds in the two words exhibit a sound device called assonance, or the repetition of internal vowel sounds. Similarly, the writer demonstrates the effectiveness of alliteration, or the repetition of initial consonant sounds, in “and the short still arch of the separate big drops, silent as a held breath.” It bears noting that -s is the most frequently found consonant in English.

I’ve been making the case that Agee’s “Knoxville: Summer 1915” is a beautiful, precise, and stylized specimen of rhetoric. The editors of the Partisan Review apparently thought so too when they published the piece when Agee was only twenty-eight years old. Agee’s account of how the prose poem came to be written at first seems at odds with the formulations offered here. Agee described his oratorio as an experiment in “free writing” and “improvisational.” He also maintained the entire thing took ninety minutes to write. I suggest even if his intent was to create a novel and unique style, his particular education would be averse to letting him do that.

As mentioned earlier, Agee attended the prestigious Phillips Exeter Academy, in Exeter, New Hampshire. (Exeter was rated by Forbes the number one private high school in America in 2022.) The curriculum the incipient author encountered there was daunting by today’s standards. Required courses included the following: Latin, Authors and Composition; Greek, Authors and Composition; Mathematics; French; German; Physics; Chemistry; Ancient and Modern Literature; and Declamation. Agee’s classical education inevitably influenced the way he wrote. He was certainly no autodidact as a good many early twentieth century American writers were, most notably William Faulkner. (Ironically, Faulkner’s lack of formal education may have been the reason for his singular genius. He had no models to follow and set out on his own.)

Upon its publication in 1938, the prose piece received little attention. Then in 1947 Samuel Barber adapted the work for voice and orchestra with the Boston Symphony under Serge Koussevitzky. Although the piece is traditionally sung by a soprano, the text is in the persona of a male child. Barber’s excerpted version drops with nostalgia and sentimentality that I’m not certain Agee intended. To my thinking, the poem is as much an existential search for identity, as the concluding sentences suggest:

All my people are larger bodies than mine, quiet, with voices gentle and meaningless like the voices of sleeping birds. One is an artist, he is living at home. One is a musician, she is living at home. One is my mother who is good to me. One is my father who is good to me. By some chance, here they are, all on this earth; and who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying, on quilts, on the grass, in a summer evening, among the sounds of night. May God bless my people, my uncle, my aunt, my mother, my good father, oh, remember them kindly in their time of trouble; and in the hour of their taking away.

After a little I am taken in and put to bed. Sleep, soft smiling, draws me unto her: and those receive me, who quietly treat me, as one familiar and well-beloved in that home: but will not, oh, will not, not now, not ever; but will not ever tell me who I am.

The question “Who am I?” plagues all of us who are subject to the human condition.

Afterword

During my ten years teaching at the University of Tennessee, I often taught James Agee’s “Knoxville: Summer 1915” to undergraduates. My habit was then to lead them on foot from McClung Tower a couple of blocks to 1905 Highland Avenue. Our stated purpose was to see if we could locate any vestiges of Agee in the neighborhood of his youth. Students were shocked to find that Agee’s homestead had been bulldozed to make way for an apartment complex.

After one of our treks there, I wrote the following poem dedicated to Robert Coles, Pulitzer Prize recipient, Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry and Medical Humanities, and James Agee Professor of Social Ethics at Harvard University. Dr. Coles was kind enough to write the introduction to my volume of poems, Death, Child, and Love:

On Reading James Agee to My Students on Highland Avenue in Knoxville, Tennessee

(For Robert Coles)

Without a nod you give yourself to us

Where hedges grew and trolleys screeched on track

and you once played without a trace of fuss

the swollen games of children back to back.

A hump-backed sidewalk stretches at the seams.

Here once James Agee woke from awkward sleep

to find a father lost in all but dreams,

no more to hear the sound of crickets’ peep.

A coughing truck drowns out my elegy.

We watch until we’re sure it’s out of sight.

Steep faces fold at all that’s left to see

of limbs whose touch is ever more than light.

In corridors of feet just passing through

we hum the troubled love that’s left of you.

For more information about James Agee on Appalachia Bare, please visit the following articles:

- “On the Other Side of Agee“

- (Poem featured with small gallery) “On Reading James Agee to My Students on Highland Avenue in Knoxville, Tennessee (For Robert Coles)“

**Featured image (cropped) from James Agee Web

![James Agee's childhood home 1505 Highland Ave Knoxville - [Knoxville Summer 1915] by Elaine Fine on Musical Assumptions website Saturday, April 10, 2020](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_683,h_647/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/James-Agees-childhood-home-1505-Highland-Ave-Knoxville-Knoxville-Summer-1915-by-Elaine-Fine-on-Musical-Assumptions-website-Saturday-April-10-2020.jpg?mip=1)

Your meditation was my education. It is of this enlightening analysis of Agee’s prose poem, I appreciate.

Jimmy: Thank you so much. I’ve had plenty of time to ponder Agee’s work over what are are now decades. Knoxville has never been kind to its writers, and Agee is no exception. When I was junior faculty at the University of Tennessee, none of the senior faculty had ever heard of Agee. Some few of the citizenry (including me) proposed that the city establish a James Agee Park with a street named for him. After some years, the city complied. So if you’re ever in K-town on 17th Street, keep an eye out for a street sign marking the intersection of James Agee Place and Phil Fulmer Boulevard. I suspect Agee would have enjoyed the irony.

Great meditation. MADE me think about the way the past is recreated, and Agee as you express did it eloquently showing off his accumulated skills from a deeply rooted application of his classical education. Your poem was brilliant..as the train screeched by….

Ed Francisco, since my retirement from teaching/educational administration, I have slipped back into my roots as an English teacher. My latest obsession has been James Agee. I had already read A Death in the Family (my aunt’s estate contained a first edition) but just finished The Letters… and Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. My obsession drove me into further research during which I came across a wonderful article about the introduction to A Death in the Family. It was written by Ed Francisco. Hmm. I thought. I know that name. I remember that delightful family… Dad, Mom and precious son. So, I’m writing to tell you how much I loved the article, how much I am disappointed not to have been a student in your James Agee class and how much I enjoyed your family at Chilhowee School. I hope you, Linda and Gabe are all doing well. My research tells me you have enjoyed a wonderful career. Vicki Andrews