Highway 27 is a two-lane ribbon connecting Chattanooga and Dayton, Tennessee. It passes through the small, unincorporated township of Sale Creek in northern Hamilton County. The locale takes its name from the creek which runs through it. The creek got its name from the auction held along its banks consisting of goods and arms taken from the Cherokee following a raid in 1799. The area was occupied by the 6th Union Tennessee Infantry during two months of 1863.

After the Civil War, Sale Creek and the surrounding environs experienced an influx of Welsh-born immigrants from coal-mining areas in the north, chiefly Pennsylvania and Ohio. Seams of high-quality coal were discovered in Sale Creek, and, in a few decades, Welsh miners contributed to operations in mining throughout the region. My ancestors were among those settlers strip mining coal.

By the early twentieth century, mining and farming were the chief modes of making a living for inhabitants of the community. Before long, churches and schools dotted the landscape. The federal government built a post office. Families put down roots flourishing for generations. Over the course of time, people died and were buried in picturesque cemeteries on sloping hills or adjacent small country churches.

My mother’s people are interred in the Welsh Cemetery. Visitors can drive a narrow lane to the top of a hill, park, get out, and enjoy a panoramic view of the rural landscape. Family members are typically buried beside each other. For example, in my mother’s family’s plot are buried my mother, grandmother, great-grandfather, great-grandmother, and great aunt. Because my grandmother and grandfather were divorced, my grandfather’s grave is farther on down the hill. Of family members, my great grandfather, W. B. Thomas, a coal miner, died at age sixty (1885-1945) from the scourge of Black Lung disease.

Of particular interest to me are markers chronicling the life and death of Welsh immigrants. Places of birth in Wales are typically long and resistant to pronunciation. This fact should come as no surprise given that the longest place in an English-speaking country is Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwillantysiliogogogoch, a town on the island of Anglesley off the coast of North Wales. (I’ve been there. It’s an awfully big name for an awfully small place!)

The surnames in the cemetery are ones common in the United Kingdom: Griffith, Kennedy, Davis, Wall. In this time of pandemic, I’m struck by the number of infants and small children interred here, hearkening back to earlier epidemics of influenza, typhus, and small pox. As a child, my grandmother was afflicted with small pox. At times, she’d trace the star-shaped explosions of scars she wore like patches on her arms, reminders of how harsh and brutish life can be for everyone, but especially for children. The proof resides at my feet: a stone reading Vivian Grace Gross: May 2, 1931 – May 4, 1931. The grief of parents is palpable here.

There is a pervading peace amid these stones that makes leaving difficult. In such a place, the dead tug at the living to stay. They whisper in the breezes on this spring day. The thought of departing saddens me as it always does when I visit here. I feel that I’m leaving part of myself behind. I beg the dead’s pardon and recall the plight of mourners with only one alternative available to them, as seen in the final lines of Robert Frost’s poem, “Out, Out”:

And they, since they

Were not the one dead, turned to their affairs.

The next leg of the journey finds me driving to a smaller cemetery where my father’s people are buried adjacent the New Providence Methodist Church, a modest, one-room edifice serving a small congregation of families for more than a hundred years. Founded by my great-grandfather, Henry Clay Francisco, a Confederate veteran who lost an arm at the Battle of Shiloh, the church enjoys a history of dynastic succession wherein tombstones memorialize the names of decades-long churchgoers. Surnames found in this country graveyard include Iles, Shipley, Elsea, and Downey. My grandfather, George Washington Francisco (1881-1950), and grandmother, Arleva Shipley Francisco (1879-1950), are buried side by side. Aunts and uncles are here, as well. The saddest sight is of two tiny headstones, each constructed in the shape of a stone lamb. Here lie my father’s infant twin sisters who succumbed to the flu in 1918.

It’s humbling to walk among the ancestral dead as they beg a word of assurance as proof of our witness they didn’t live in vain. Maybe it’s enough for us to say we are their children in the light of humanness and have no more answers for our predicament than they had for theirs.

My thoughts next turn to poems inspired by the momento mori around me. There’s Allen Tate’s “Ode to the Confederate Dead”:

Row after row with strict impunity

The headstones yield their names to the element

The wind whirrs without recollection.

Then William Carlos Williams’ “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime”:

Sorrow is my own yard

where the new grass

flames as it had flamed

often before but not

with the cold fire

that closes round me this year.

Thirty-five years

I lived with my husband.

The plumb tree is white today

with masses of flowers.

And, finally, Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”:

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree’s shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mould’ring heap,

Each in his cell forever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

Our best poets all have tried to make sense of insensible death. All have failed. Even Shakespeare recognized the impossibility of this task, describing death as “the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns.” On leaving the cemetery and heading back to the car, I wondered what the dead would have to say about dying. What wisdom could they offer us? That’s when I spotted an epitaph, still legible on a weathered tombstone, as if imparting a message just for me:

Remember, friend, as you pass by

As you are now, so once was I

As I am now, soon you will be

Prepare for death and follow me.

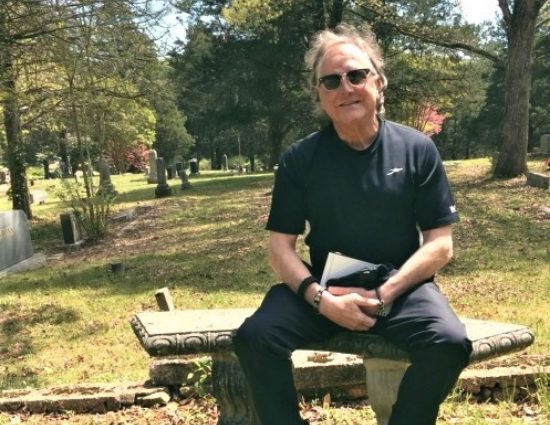

**Featured Image(Cropped to fit): Linda Francisco is the photographer for this image and all other images (with exception of the New Providence Methodist Church) on this post.

Eddie, whenever I visit a graveyard, I think of Masters’ Spoon River Anthology and wonder about the stories beneath the markers. Thanks for giving life to your ancestors and sharing their stories. I especially appreciate your poetic perspectives.The contemplation of our fragile humanity in the face of the diseases and tragedies that are our lot is humbling: Our “modern” society struggles still with ancient maladies.

Thank you, Jimmy. As I pass the stones, I imagine or make up) histories for those buried there. As a boy, I was scared of cemeteries until my dad said to me one day: “It’s not the dead you need to worry about. It’s the two-legged living kind you need to be concerned about.” Sadly, he was right.

That was a really nice read and the photos are professional. I always feel a stillness when i visit a graveyard. I enjoyed the exerts from those poets which illustrate the inability of even our poets to penetrate the mystery and mystic in the dead.

As always well done. This is growing into a great platform to expose the world to the unique history and artistic talent of Appalachia!

When our family moved to East Knoxville five years ago, I took my children on the adventure of finding my great-grandmother’s grave. I knew she was buried somewhere close to Ritta Elementary School – an area of many burial places.

Nanny, they called her, and she impressed her grandchildren by singing the alphabet backward. I discovered many markers bearing the name Blackburn. This area is full of cousins from a branch I barely knew, but I know more of it now. After finding her stone, I realized her maiden name was Weaver. So that is why our family has so often used Weaver Funeral Home though the Weavers no longer run it.

Last weekend my husband lamented being unable to find his childhood best friend on Facebook due to common first and last names. With the help of my in-laws, he remembered his friend’s parents’ names, and I started searching obituaries that mentioned all three names. I found record of the friend’s grandmother along with an aunt and cousins with less common names and found their profiles. Perhaps now they will reconnect?

As much as technology makes current events different from past reminders of mortality, we still meet again at funerals and weddings. Beginnings and endings.