Slate Creek Road turns to gravel at the top of the hill before you reach the trailers that squat on the ridge. The steep, rutted road appears to lead straight into the sky. The last stop—three old trailers at one of the highest points in Boyd County, Kentucky.

Randy has an old Ford Pinto, but what he lacks in horsepower he makes up for in heedlessness. Kim used to laugh like crazy when they screamed up the hill in that old rust-bucket. Now that she’s pregnant, she holds her breath every time they rocket up to his family’s trailer.

The welcome she receives when they arrive is worth the terrifying seconds on the road. The white trailer with green trim always smells comfortably of cooking, with the odor of coffee and cigarettes overlaying the rest like a familiar blanket. The cigarettes remind Kim of Randy, and Randy means home.

“Mom, we’re home,” Randy says, scuffing his feet on the entry rug. Mary Jo, Randy’s mother, has laid a plastic runner from the front door to the kitchen to protect her carpet. A Married With Children rerun is blaring on the television, and the smell of hamburgers frying comes from the kitchen.

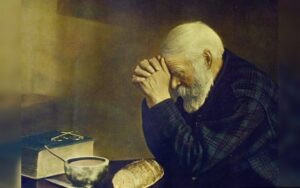

A picture of an old man, his head bowed over a meager meal of soup and bread, hangs above the table in the paneled kitchen. Kim has seen that picture in nearly every kitchen in Ironville, Kentucky, except her own. Her father says art is vain. The closest that Kim’s mother ever got to kitchen decorations was homemade plaid curtains and potholders.

Randy mutters that he’s going back to the car for Kim’s suitcase just as Mary Jo says, “Well, take off your coats and stay awhile. Where did he go?”

“My suitcase,” Kim says, half-embarrassed even though Mary Jo has been insisting that she move in since she found out about the baby.

Kim’s father had the opposite reaction.

“Out Jezebel!!!” he shouted that afternoon, when Kim’s mother finally made him understand what Kim was trying to say. He gave her 15 minutes to pack while her mother stood in the shadows with tears shining on her cheeks. But Kim knew that her mother would prepare her father’s dinner that night as always, and they would watch TV in silence until they went to bed.

“Well, honey you just settle in. There’s some space in Randy’s closet for your things,” Mary Jo says as Randy comes back with Kim’s bag. “And we’ll get you over to the courthouse just as soon as we can to make things right. Until then, Randy can sleep on the couch.”

Kim nods as she walks back through the dark, narrow hallway. Her chest feels tight.

Marriage.

Then she relaxes.

Freedom.

No more unending silence. No more curfews. No more belts.

Kim smiles as she walks back into the kitchen. Mary Jo is setting dinner out on the flowered oilcloth that covers the small table. Four plates of hamburger, baked potatoes, and green beans. There is a chess pie for dessert.

Kim sits down beside Randy. “I’ll do the dishes,” she says as Jimmy, Randy’s father, comes in.

“Smells like snow out there,” Jimmy says. “There’s my favorite girl.” He kisses the top of Kim’s head.

“I thought you was talking about me,” Mary Jo says, slapping him on the shoulder.

“I hope they call school off tomorrow,” Randy says.

“You need to be thinking more about finishing school than skipping school,” Jimmy says. “You ought to look into one of them vocational programs at the college so you can take care of Kim and the baby. Bosses ain’t takin’ on natural-born mechanics like me anymore.”

Randy looks down at the table. This is the part they don’t talk about—the day-in-day-out, grocery-getting, paycheck-earning future.

Randy wants to be a race car mechanic, and he can do anything with a car. But the closest big racetrack is in Bristol, Virginia, and all he has right now is a weekend job at Mike’s Garage.

When Kim thinks of being anything at all, she wants to be an artist. But she knows art doesn’t pay. Most of her friends want to be nurses.

Kim puts art out of her mind. She doesn’t want to be anything. She just wants to be. Right here in this kitchen right now, she feels safer than she has ever felt in her life. She knows Randy’s parents will help them. She knows they will never be rich, or even well-off.

She puts her hand on Randy’s knee under the table and smiles at him. He looks at her and smiles back, then digs into his baked potato.

Growing up, Kim thought supper meant silence and chewing. But at Randy’s house, Mary Jo prattles on about her day taking care of three-year-old twins for a teacher from the high school. And Jimmy tells the gossip he heard at the diesel garage. Sometimes Kim even screws up enough courage to talk about something she saw or learned that day.

They tease her about being quiet. “Our Mouse,” they say. But they smile when they say it, and she knows the nickname means she is part of the family.

“I told you it smelled like snow. Look-a here.” Jimmy cranks the window open, and the sharp air of the blue-black night strikes Kim in the face. They watch the snowflakes fall. They will cover the ridges and roads overnight and make Ironville beautiful.

After dessert, Kim clears the table and does the dishes, enjoying the warm suds on her hands. Pretty soon, she’ll have to take off her wedding ring before she starts the dishes.

Much later that night, Kim awakens alone in Randy’s bedroom. She stands to look through the gauze curtain at the snow drifted against the trees. To Kim, the snow glittering beneath the stars looks like diamonds.

Randy, lying on the couch covered with an old plaid blanket, leans up on one elbow to look out the front window. He grins. At least four inches of snow. No school tomorrow.

Leigh Ann Roman is a native of Eastern Kentucky who makes her home in Memphis, TN, where she works in higher education communications. Her poetry and creative non-fiction have appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Appalachia Bare, and Faith West Tennessee. She has a master’s degree in strategic communications from the University of Tennessee at Martin.

**Featured image credit: Music Meets Heaven, Unsplash