We Southerners cherish our “characters” – eccentrics and outliers who intensify the spiciness of life. Take William Faulkner. To his neighbors in Oxford, Mississippi, Faulkner was “count no count,” a little bitty fellow who put on airs while sporting a limp and a cane and donning a cape for his morning walks around the town square. Not until the author won the Nobel Prize in 1949 did public sentiment toward Faulkner begin to thaw. Nowadays almost everyone in Oxford claims at least a peripheral biological tie to America’s greatest literary Titan – even down to the young Vietnamese clerk at the Jitney Jungle who once gave me directions to “Uncle Bill’s Rowan Oak Estate.

Or how about the zany performances of the Southern Belles, and good ol’ girls in the hit TV series Designing Women, its creator, Linda Bloodworth Thomason. One scene showing our affection for odd sorts involves Julia Sugarbaker, played by Dixie Carter, explaining to a visitor why we accommodate family members who appear at times to be a “bit off”:

Julia: “I’m saying this is the South, and we’re proud of our crazy people. We don’t hide them up in the attic. We bring ‘em right down to the living room and show ‘em off. See, Phyllis, no one in the South ever askes if you have crazy people in your family. They just ask what side they’re on.”

Phyllis: “Oh? And which side are yours on, Mrs. Sugarbaker?”

Julia: “Both.”

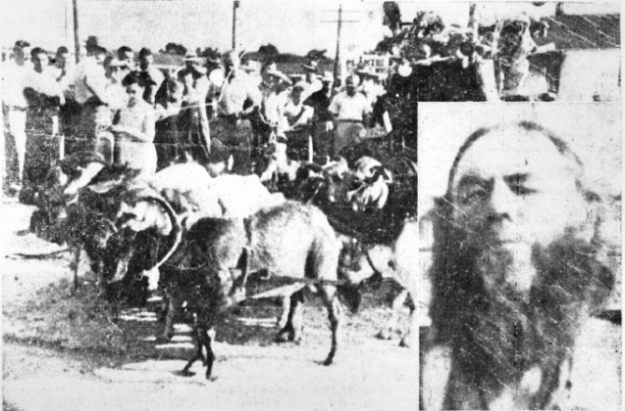

Of course, we don’t have to restrict ourselves to literature, TV, and film to unearth an honest, true-to-life “character.” Those readers of a certain age may recall hearing about or seeing an itinerant wanderer who from 1930 to 1987 was a fixture on the Southern landscape while riding in a ramshackle wagon drawn by a team of goats. He was dubbed by all who saw him as the “Goat Man,” or variously, “Billy Goat Man.”

Born Charles “Ches” McCartney at the turn of the century in Iowa, McCartney ran away from his family’s farm home at age fourteen. Soon afterwards he found himself in New York where he met and married a Spanish knife thrower ten years his senior. McCartney became part of the act, serving as his wife’s near-miss target. With the advent of the Great Depression, the duo gave up carnival life and unsuccessfully attempted to make a living as farmers. Fed up with poverty, his wife walked out on him one day before dawn. He married at least two other times, reputedly selling one wife to an interested farmer for $1000.

Having been fond of goats since his days of working on the farm, Ches McCartney hatched the idea of using a goat cart to travel the country as an itinerant preacher. He claimed to have covered 100,000 miles and visited all states but Hawaii, explaining that his goats couldn’t swim that far, and even if they could, “they’d just end up eating the grass skirts off the hula dancers.”

Wherever McCartney and his goats made an appearance in one of innumerable locales throughout the Southland, crowds flocked to see him. Of course, some smelled him before catching sight of the eccentric wanderer. The goat odor was so stifling as to announce his presence before he arrived. Between marriages, he claimed not to bathe, explaining how he and his goats didn’t mind one another’s ripeness. At dusk McCartney’s habit was to park his wagon and goats on the side of the road, build a bonfire, and chat with locals. He always left them with a message: “Prepare to meet thy God.”

Whether his intent or not, the Goat Man invoked a carnival atmosphere wherever he traveled. In his book America’s Goat Man (Little River Press, 1994), Daryl Patton describes McCartney’s vehicle of choice:

McCartney’s iron-wheeled wagon was large, rickety, and garishly decorated with a clutter of objects he found and collected along the road. It contained a bed, a potbellied stove, lanterns, and lots of trash, and was pulled by a team of around nine goats, with a few trailing behind to occasionally push and serve as brakes on downhill stretches of road. His traveling goat herd sometimes numbered up to thirty.

We could expect that someone so obviously Gothic would attract a writer like Cormac McCarthy. In his 1979 novel Suttree, set in and around Knoxville, Tennessee, McCarthy’s protagonist Sut converses with the Goat Man on the outskirts of Dixie Lee Junction:

Sut: What you want with these goats anyway?

Goat Man: Little or nothin. Good fresh milk. God’s best cheese.

Sut: You have any other animals? Dog or anything?

Goat Man: No. Just goats. I think a fellar gets started with goats he just more or less sticks to goats.

My own experience with the Goat Man occurred when I was five. My parents and I were traveling home from a visit with my grandparents in north Hamilton County, near Sale Creek, Tennessee. The road we were on, Highway 27, was a two-lane ribbon with shoulders wide enough for cars to pull off safely. A line of vehicles was forming. One or the other of my parents exclaimed, “It’s the Goat Man!” Daddy eased our Buick off the road’s edge and onto the grass.

There in the field, the Goat Man tended his signature camp fire surrounded by his goats. We exited the car, joining other curious onlookers. Children ran wildly about. Approaching, I caught sight of him. Sporting long hair and a grizzled beard and wearing threadbare, scruffy clothing, he might have been an ogre in a scary dream. But there he sat in the flesh, hawking postcards featuring a picture of himself and his goats. One card cost two cents.

“Would you like a postcard?” Daddy asked.

Of course! Who wouldn’t? Daddy dropped two wheat ear pennies in my awaiting palm.

“Go ahead. Give them to him,” Daddy urged.

I moved gingerly. The closer to the Goat Man I got, the more pungent was his odor. He held out a rusty hand with a postcard. I breathed again when the transaction was completed.

“When you get home, you’ll need to take a bath and wash the goat off,” my mother said once we were back in the car.

The next morning, I took my card to kindergarten with me. Children crowded around to see my picture of the Goat Man and his goats. When the teacher asked me to put it up, I placed it in the cubby labeled with my name. Thinking it secure, I went about the hard work of playing. When parents started picking kids up, I scurried to my cubby only to discover my postcard gone. Some nimble-fingered kindergartner had stolen it.

Ches McCartney continued his rickety ramblings throughout the South for years afterwards, eventually living out his last days in a nursing home in Macon, Georgia. He died in 1998. Found in his possession were copies of the Bible and Robinson Crusoe. At the time of his passing, he was believed to be in his late nineties. However, true to the spirit of his legend, he had claimed to be 106.

All newspaper clippings and images are from the Library of Congress

**Featured image from Adalia Botha on Unsplash

I enjoyed this humorous take on the Goat Man and our Southern “characters.” Steve Bowman’s dad once took me along on a family excursion into the Tennessee countryside to meet the Goat Man. Your description was spot on— especially the distinctive aroma of the Capra clan.

Performance art at its smelliest