My father passed away from cancer July 19, 2014. When he was almost completely bedridden, he and I listened to an audio interview of an old family friend. My father broke down and said, “Just think of all the stories I could tell but never will.” I vowed right there I’d tell his story whenever I had the opportunity. One thing I asked for upon his passing was a journal he kept, a memoir, which he wanted to someday publish. Sometimes, going through a loved one’s papers and belongings brings so much grief you just want to put it all away until a time when you can better deal with it. For me, that time is now. On occasion, I’ll bring his story to light in excerpts from this memoir. – Delonda Anderson

Introduction: War, Vet to Vet, Vietnam

I can tell you’ve been there by the way your eyes move. I see the worry when you smile. Certain sounds, certain smells bring it all back to 1966.

We were not yet men, but just children – scared, hungry, wet, alone among many. Some never came back, not even dead or alive. A part of all of us is still there. We see in flashbacks – a familiar sound, a smell, a color red, blood red. A gun shot, the sound of a chopper, a plane, a jet, a track. You can’t stop the human mind. [It’s] recorded forever. That’s the part of life’s tape that can’t be erased, the part we [lost]. The forgetfulness. Why? Because you trained yourself to forget. I remember it all at times. A man will cry. It can’t be helped. Even an animal cries out when in physical pain, but mental pain is sometimes worse.

I remember going into [B –] Camp, picking up supplies, going to the medicine tent for a sore throat. I remember the sound of a medicine chopper. I remember the nurses ran to meet it. I remember they tore and cut a G.I.’s jungle fatigue shirt soaked in blood. He was a dark blue, his chest full of maybe six or seven holes. He was lifeless but they worked from the chopper to the sandbags where two doctors stood ready. The nurses threw the blue, lifeless body onto a table with instruments. I watched through an open flap as a long, deep cut was made the length of his chest. I watched a hand work desperately on a heart. I saw with my own eyes the color change to a light pink. I saw red blood and heard a gasp for air. I saw him breathe. I walked away. He had won his fight for now. It made me wonder.

Excerpt One

It was September 18, 1966 when I stepped off that big plane into a world filled with the fear of Death all around me. I was just a Hillbilly from LaFollette, Tennessee, a small town where life was simple but hard. I was so proud of my country, proud that I was serving her, and proud that I was allowed the honor of following in my Daddy’s footsteps, unaware of all the heartache it caused back home, 14,000 miles on the other side of the world. I saw from the corner of my eye the [emblem] that struck fear in our adversaries, as beautiful as ever, waving to me. I looked upon all her splendid threads, gazed deep into her proud past, and saw what I believe every American boy sees. Yes, we were all just boys. But soon, very soon, we’d become men. I envisioned the reflections of thousands and thousands of souls drenched in blood. I thought the chance was very good that my reflection would also be wrapped in the warm womb of a country that I was so in love with and would defend her honor even if the supreme sacrifice must be paid. I then and there called upon the first love in my life – God Almighty – to please walk through this Valley of the Shadow of Death with me and to see me through.

I looked back to the staging area where, for that brief moment in time, I was at ease with all. Hundreds of other boys stood with me, some Black, some Hispanic, some White, like me. God-fearing souls with the same color of blood carrying M-16 and gear, [were] ready to defend our beliefs as one, knowing that we were sent to replace fallen comrades, who once stood, no doubt, in the same spot where we now stood. I thought for an instant that maybe I was wrong and things wouldn’t be so bad after all. Then I noticed the pilots exit the big plane and walk under the wings and the belly of their plane. I stepped up to one of them. He was a big man, maybe in his 50s. I asked him,

“What are you doing?”

He said,

“Looking for bullet holes, son.”

The chill returned. Reality took over again. But it was so peaceful here, I thought. At a distance, a sergeant called my name and asked where I was from and to see my orders. I said,

“But Sarge, it looks so peaceful here.”

He said,

“Just wait until tonight, son. B-Btry. 29 Arty. S.L.T. Division.”

He gave me some papers and said,

“Take your gear and stand over there.”

I heard a rumble in the distance. Then I saw them. Five D-model Hueys coming straight at us. They never circled. They came straight down and landed.

In seconds we were in the air – my first chopper ride. I was scared to death. This was the second time I had been off the ground. The first time was on that big plane that brought me here. I looked out the open doors and saw the jungle and rice paddies below me. I saw a few people dressed in what looked to be black pajamas and funny looking hats. Some kids [were] riding buffalos. A hill afar off looked like someone took a big butcher knife and just cut the top off, flat. We started down and I asked [the crew],

“What is this place?”

They said,

“This is home for a while.”

The chopper again never circled. It went straight in and we were off and it was gone. I felt so alone, like an animal must feel when it’s just been hauled to some backroad and set off. But then you think, I’m an American fighting now and I’m well trained. Now is the time to use it. The sun was setting and I was glad because it was so hot there. I stood and watched that big sun slowly disappear in the west and thought of home and all those evening hours I sat outside on College Hill when I was a boy waiting for Daddy to get off work and eat supper. I saw some boys come out of a bunker. There were seven of them, one with an M-16 and an M-79 grenade launcher hung on his shoulder, one with an M-60 machine gun, one with a radio pack, and one with a mortar tube. The other four had several belts and ammo boxes and M-16 rifles. They stopped and welcomed me. Their faces were young but wrinkled with aging lines as if they were [so much older]. They were as cautious as a cat. Their [senses] caught even the slightest movement or smell.

“Well, let’s do it,” the one in front said. “I’ll take the point.”

And out over the hill they went as darkness fell. I didn’t see or hear anything for the next few hours. Then, I heard a chopper in the distance. Sounded like one, then two, maybe more. This time they circled big. The sky lit up from the ground with traces from the crack of an AK-47. I heard all kinds of gunfire and heard the bone chilling voices in broken English,

“G. I. you die tonight!”

Those words terrified me. A swishing sound came from the choppers – Aerial Rocket Artillery (ARA) rockets sprayed death and destruction and miniguns were firing. It sounded like rain falling all around that hill. It’s something I’ll never forget – the smell of burning flesh mixed with gunpowder. For me it became a way of life for the next year.

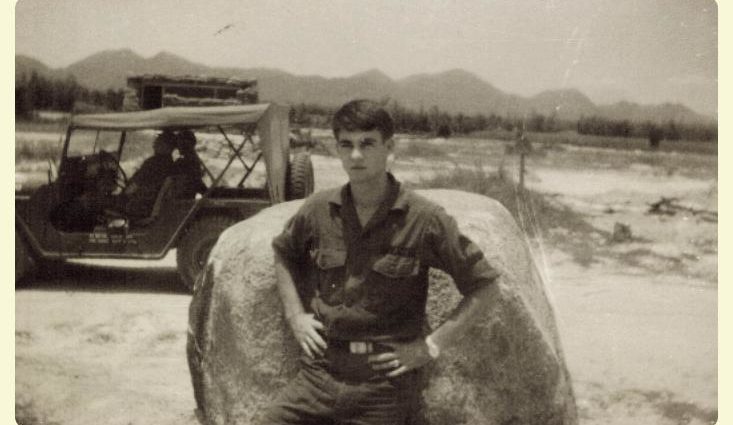

I soon found out “S.L.T.” was a Search Light Crew of two men. I was the operator of that searchlight. At the time, they were mounted on a Jeep, 150 billion candle power with infrared capability. I didn’t know it then but it helped me survive the months to come. I was glad I could see at night and learned my job as fast as I could. Little did I know that I was now a target, and, if found, one that must be taken out. Sergeant Villirea knew his job well. The next week or so, we took turns running missions around that hill in the middle of nowhere, looking in the valleys below for Vietnamese aggressors, N.V.A., or, Charley, as we later called him. It was my job to find them before they hit us on the Landing Zone (L.Z.). That was what this hill was, an L.Z. cut off at the top for quick access for choppers to deliver supplies and such.

Soon after our L.Z. was made secure and the firefights slowed to an occasional skirmish, we had orders to make ready. We were moving out. I remember thinking, Oh Lord, I got to drive this Jeep through the jungle and rice paddies. I thought about mines and booby traps, ambushes, and on and on. Then Sgt Villirea brought out a 4-point web belt with a big steel eyelet and four hooks. We hooked it to the bumpers on all four corners. He said,

“Load your duffle bag up. Get your rifle and ammo and the M-79 and let’s go.”

I heard another chopper. It was a Chinook, a big twin blade chopper. We sat in the Jeep and the chopper hovered over us like a dust storm. We hooked the eyelet onto a big cable underneath and away we went in about 30 minutes. We spotted another hill, farther north this time, with a lot of people. It was An Khe, the Base Camp of the 1st Air Cavalry Division. This would be my last assignment. I was now in the 1st Air Cavalry Air Mobile S.L.T. Unit. We stayed there about three weeks, then went to L.Z. English and to L.Z. Geronimo. This L.Z. overlooked a big valley and there were villages below. We were taking casualties there and they needed an S.L.T. to find the snipers. Here we were – tired, cold, and hungry. We finally got our sandbag bunker “hootch” in order and settled down to rest after a meal of C-rations, which tasted pretty good if you were hungry. But they ain’t nothin’ like Mommy’s cooking. I sure did miss home. I tried not to think about it but I couldn’t help it. I thought sure I’d die I hurt so bad inside. I didn’t know if I’d ever hear from home again, but, next day at mail call, I’d get at least one letter, sometimes bunches of them. I knew somehow God would get me through this.

One night our Captain told us we’d probably be overrun and to be ready for anything. This was to happen in the next 48 hours and we were to prepare for the worst attack ever. He said,

“Boys, write a letter home. It might very well be your last.”

I wrote that letter to my mother. I told her I was fine and had it made and was in no danger. I told her I loved her and Daddy and to take care of my future wife. I honestly thought it would be the last time I’d write home. I spent the next 48 hours in a bad state of mind. We fired on anything that moved outside the constantine razor wire. I took two cases of grenades and my rifle, and took up a position in a ditch overlooking the valley. As soon as dark came, we started our Jeep and the infrared missions. But this night was different. We moved about halfway from our last position then here it came – a chunk, chunk, chunk sound and then the wheer, wheer, and Boom! Boom! Mortar had hit our last position. I saw a flash of fire and the searchlight went silent with a crack. It took an AK-47 round. I opened a case of grenades and threw them down the ditch, like a pitcher, one after another. Five 105 Howitzers on the L.Z. were firing, M-60s were firing, M-16s were rattling. It was Hell for sure but we kept Charley in the valley. He kept coming. Then the choppers, the Air Borne, came. God, it was a wonderful sound. They fired rockets and ARAs. The choppers went around to the back side of the L.Z., and the noise of their prop blades lessened. Then, I heard a plane. It was a Spooky, a fixed wing. That was her name – Spooky. I knew little about this plane, only what I’d heard, but now saw firsthand. She turned, tilted her wing and began to lay down a stream of fire that looked like somebody poured hot metal from a steel vat from the sky. I never saw anything like it in my life. She made a few passes and was gone. It was over and, in weather that sometimes reached 130° F, I shook like someone freezing to death. It was just a nervous reaction. It only lasted two or three hours, then I was at myself again. The worst is over now, I thought. Then came morning.

Harrowing and moving account – descriptive and in the moment. I’m glad your father is getting to tell his stories through you, and I’m eager to hear more. I recently read Daniel Ellsberg’s memoir, Secrets. I was struck by how the troops narratives were so different from the “stories” the American people were told by their leaders.

Thank you, Jim. Yes, their narratives are quite different for sure. In reading my father’s journal, I found it heartbreaking how lonely he was there. As he put it: “alone among many.” A little anecdote about how young and small he was when he was drafted . . . One evening, he had my nephew try on his uniform and it fit him perfectly. My nephew was thirteen at the time.